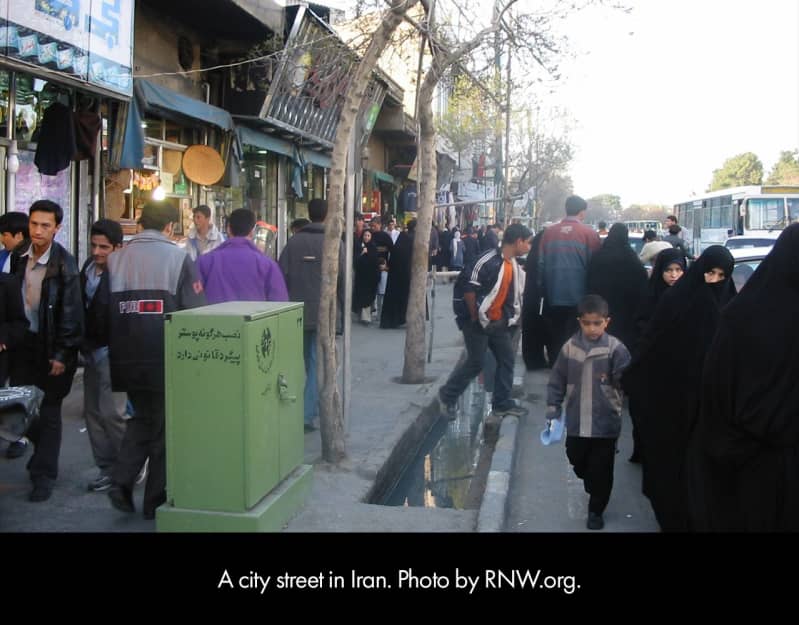

English takes place in Karaj, Iran in 2008. Prior to the Iranian Revolution of 1979, Karaj was a satellite city about 30 miles west of Tehran. It was primarily a center for industry and agribusiness. In the past few decades the city has grown considerably. Metropolitan Karaj, with a population of 2.5 million, is now Iran’s fourth-largest city. It has a mix of social classes, with many of the residents having moved away from the congestion and high cost of living in Tehran. To better understand the stakes and circumstances of English, let’s look at some of the key sociopolitical factors affecting the time and place.

Jump to:

The Revolution of 1979

The 1979 revolution was a major turning point in Iran’s history. The Shah—the sovereign ruler of the then-monarchy of Iran—Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, was overthrown by a mass revolution encompassing Iranians from different social backgrounds and political persuasions. The revolution was ultimately led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini.

Khomeini, who had been previously exiled by the Shah for speaking out against him, preached that the Shah’s White Revolution, an aggressive and expensive modernization program, had made the country economically unequal and led the country to turn its back on Islamic principles. Khomeini warned that the Shah’s close political ties to the West would uproot traditional Iranian culture and overall sovereignty. In late 1978, religious students, economically disaffected young people, opposition leftists, and nationalist political groups took to the streets to protest the Western-tinged excess of the Iranian monarchy. After months of strikes and unrest, Iran’s armed forces declared their neutrality, which finally ousted the Pahlavi dynasty and brought a definitive end to the 2,500-year-old Persian monarchy. This event is known as the Iranian Revolution.

Despite the broad and multi-dimensional revolutionary coalition, Khomeini took charge in the wake of the Iranian Revolution. He declared Iran an Islamic republic guided by Islamic principles and himself Supreme Leader of the land. He created a new constitution that sought to blend republican institutions such as a parliament and a popularly elected executive branch with an Islamized judicial system. Public offices were reserved for clerics. The country officially became the Islamic Republic of Iran in 1979. To this day, the Supreme Leader sits atop Iran’s political power structure, above the President. While Iran’s President and members of the Parliament are publicly elected every four years, their powers are checked by those of the Supreme Leader and the Council of Guardians—half of whom are appointed by the Supreme Leader himself. This entity is responsible for determining whether the laws passed by Parliament are in line with the Constitution and religious precepts of Islam (or Sharia).

The country’s current Supreme Leader is Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who succeeded Khomeini after his death in 1989. With Khamenei and his followers prescribing adherence to a rigid interpretation of Islam, many of the laws and policies in place in Iran in 2008 were designed to reinforce traditional values and suppress dissent. However, popular mobilization against state policies is common. It has regularly been expressed in the past three decades on the floor of the parliament, during elections, through strikes, and with popular gatherings in front of government buildings. At times this mobilization has been peaceful, but at other moments it has been met with state repression and violence.

Calls for deepening republican rule and democratizing society coalesced into the Reformist movement that gained popularity under President Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005). Reformists aspired to use their electoral support to pass legislation to modify laws and shift power away from the Supreme Leader and towards popularly elected offices and non-governmental organizations, or society at large.

Censoring Dissent

This political project was defeated by hardline supporters of the Supreme Leader who used a mix of intimidation and arbitrary powers to crack down on Reformists. In 2005, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the strictly conservative Islamic mayor of Tehran, won the Iranian presidency by running on a platform in which he pledged to return to the core values of the Iranian Revolution of 1979. Once President Ahmadinejad came to power, the government began to invoke issues of “national security” as a justification for silencing dissent among Iranian citizens and leaders of the Reformist movement. For example, the U.S. Global War on Terror and presence of U.S. troops in two of Iran’s neighbors— Afghanistan and Iraq—became evidence of plots by “enemies.” According to the 2009 World Report from Human Rights Watch, in that year Iran saw “a dramatic rise in arrests of political activists, academics, and others for peacefully exercising their rights of free expression and association in Iran.”

Iranian authorities suppressed freedom of expression and opinion during this period by arresting and imprisoning journalists who painted the government in a negative light and by strictly controlling what was published and what was taught in schools and universities. The internet was closely monitored, and websites or forums critiquing government policies were at risk of being blocked by the authorities.

A grassroots movement advocating for women’s rights, called the One Million Signatures Campaign, was a specific target of government meddling and censorship in 2008. The Campaign, co-led by the feminist activist Sussan Tahmasebi, sought signatures of support to reform Iranian laws discriminating against women and bring them in line with international human rights standards. The movement was peaceful, and yet security agents and judiciary powers prosecuted women involved in the campaign for "disturbing public opinion," and "publishing lies via the publication of false news." Despite the road blocks, the Campaign made progress toward their goals, including striking down a proposed tax on prenuptial arrangements which promoted polygamy.

Brain Drain

The pattern of “brain drain”—the emigration of highly educated or trained citizens—intensified across Iran in the mid to late 2000s, as intellectuals and highly skilled workers fled to avoid imprisonment for voicing beliefs that weren’t in line with governmental policies. During this time, dissident university professors were forced into early retirement, and politically active students were prevented from registering for their next school semesters. According to the Center for Human Rights in Iran, at least 200 students were arrested between June 2007 and December 2008, many of whom were subject to “torture and ill-treatment” for speaking out against the government. For less politically-minded Iranians, high unemployment and the unpredictable economic conditions were reasons to seek careers and opportunities to study outside of Iran. The presence of a large diaspora, who had left during the revolution or the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988), made the prospect of immigration even more tangible.

Simultaneously, rumors that Iran was secretly developing nuclear weapons became a pressing global concern. Following past attempts at curbing Iran's nuclear program, the United Nations Security Council demanded in 2006 that the country suspend all uranium enrichment and reprocessing activities. In the two years that followed, as Iran continued to defy the UN’s orders, increasingly tight economic sanctions were placed on the country in an attempt to block the import and export of sensitive nuclear materials and equipment. By 2008, the UN Security Council had adopted three separate resolutions to sanction Iran economically for its nuclear program. Despite growing evidence otherwise, Iran maintained that their uranium enrichment activities were for the purposes of civilian technology rather than weapons development. Unbeknownst to Iranians in 2008, the situation would become even worse after 2008. Under President Obama, the U.S. was able to organize an international campaign to isolate and impose severe economic sanctions that limited Iran’s ability to export oil, attract foreign investment, and import necessary goods. Under President Trump these steps were escalated into a “maximum pressure” campaign.

Economic Turmoil

In March 2008, in spite of the recent third round of UN economic sanctions, Iran’s economy was set to remain steady thanks to record prices for crude oil. But after President Ahmadinejad boosted social spending to “bring the oil money to people’s dinner tables,” Iranian inflation doubled to 30% with disastrous results. Many jobs were lost when local industries were damaged by both a flood of cheap imports and the central bank’s sudden credit-restriction policy. While this policy helped to reduce inflation, it also caused an increase in unemployment.

And yet, not everyone in Iran was facing economic turmoil. The unequal distribution of wealth was reinforced as certain individuals and social strata benefited from the state resources and an economy dominated by monopolies. Additionally, the poor housing and job markets were especially detrimental to the Iranian lower and middle classes. Overall, between 2005 and 2007, the income of the top 20% in Iran rose more than four times as fast as that of the bottom quintile, creating a dramatic increase in the country’s margin of inequality.

Iran On The Brink

2008 was a year of tension for Iran. International sanctions, a tumultuous economy, a defeated Reformist movement, and an unwavering Supreme Leader fueled a collective culture of anxiety and fear over what might come next. Learning a foreign language, as the students do in English, would have been a key step toward obtaining a visa and unlocking the door to opportunities outside of Iran.

References

|

Afary, Janet. “Iranian Revolution.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 25 Mar. 2020. “Allow Peaceful Celebrations of National Student Day.” Center for Human Rights in Iran, 8 Mar. 2012. Ardalan, Davar. “Iranian Women Demand Change.” NPR, NPR, 5 June 2009. “Inside Iran - The Structure Of Power In Iran | Terror And Tehran | FRONTLINE.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service. “Iran.” Nuclear Threat Initiative - Ten Years of Building a Safer World, Jan. 2020. Isfahani, Djavad Salehi. “Iran's Economy: Trouble in Tehran.” Brookings, Brookings, 28 July 2016. NewsHour, PBS. “Timeline: A Modern History of Iran.” PBS, Public Broadcasting Service, 11 Feb. 2010. Kaveh Ehsani, Arang Keshavarzian and Norma Claire Moruzzi, “Tehran, June 2009.” Middle East Report Online, 28 June 2009. Passanante, Aly. “Iranian Activists' One Million Signatures Campaign for Gender Justice, 2006-2008.” Global Nonviolent Action Database, Swarthmore College, 24 June 2011. “Security Council Imposes Sanctions on Iran for Failure to Halt Uranium Enrichment, Unanimously Adopting Resolution 1737 (2006) | Meetings Coverage and Press Releases.” United Nations, United Nations, 23 Dec. 2006. Tahmasebi, Sussan. “The One Million Signatures Campaign: An Effort Born on the Streets.” Amnesty International, 2012. United Nations. “Iran: Student Protests in Iran; Treatment by Iranian Authorities of Student Protestors (December 2007 - December 2009).” Refworld, 5 Jan. 2010. “World Report 2009: Rights Trends in Iran.” Human Rights Watch, 29 July 2011. |