A Personal Essay by Allan K. Washington

On the day I started writing this essay, I opened an email that I imagine most New York actors dream of receiving: “OFFER/ALLAN K. WASHINGTON”—an offer from a respected New York theatre for a leading role in a new play by a critically-acclaimed playwright.

The play is In the Southern Breeze by Mansa Ra, who Roundabout audiences will remember from his 2017 Underground debut Too Heavy for Your Pocket and whose Roundabout commission, ...what the end will be, will premiere at the Laura Pels Theatre this spring. In the Southern Breeze is being produced by Rattlestick Playwrights Theater. Rattlestick’s website describes the play,

Deep in an existential crisis, MAN locks himself in his apartment. A portal reveals itself and when he crosses that threshold, MAN begins a journey that traverses centuries of history, allowing him to create a space for his own healing, while exploring the complicated and more camouflaged barriers of today.

Needless to say, I was so hype (read: excited) when I got the news. But almost as suddenly, I felt an overwhelming pressure.

A pressure I can now identify as an urge to honor anyone in those “centuries of American history” who lived so that I can strive.

A pressure to honor those who made it possible for me to be me: a Proud, Out, Gay, Black, cis man with a dream and a skin fade.

A pressure to honor my ancestors. My Fathers and Brothers. Mothers and Sisters.

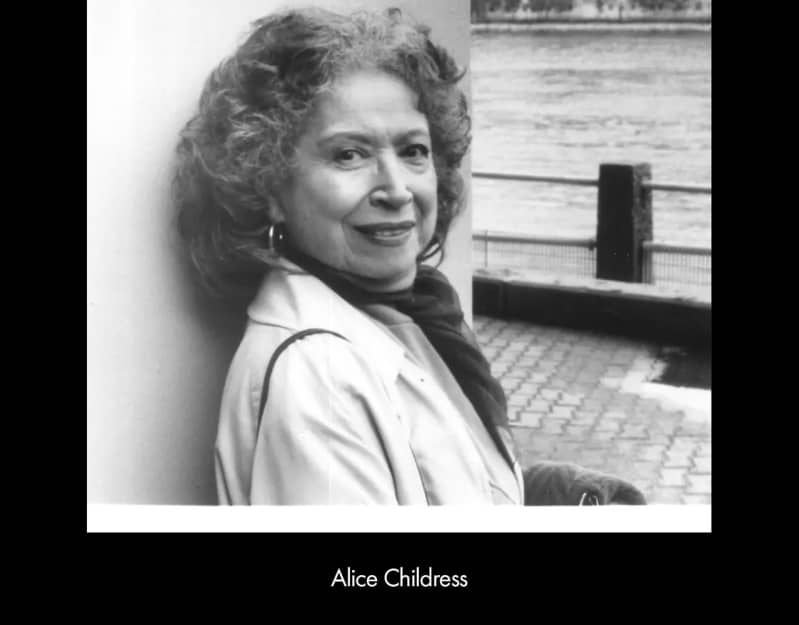

Alice Childress is one such ancestor.

I immediately think of her character Wiletta Mayer in Trouble in Mind because to me, Wiletta exists as a symbol of all the Black women—and specifically, Black actresses and artists—who have been used and abused by predominantly (and, in many instances, exclusively) white institutions for financial gain.

And yet, she also exists as an example of how to stand up and fight for the autonomy of Black women.

Today, I honor Alice Childress—a Mother and Sister of the Black theatre and an advocate for all artists.

Roundabout Theatre Company’s production of Trouble in Mind marks a glorious Broadway debut for Alice Childress: a debut during a moment in the American theatre that is reckoning with events like the very ones Childress dramatizes.

In 2020, a coalition of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color artists—under the name “We See You, White American Theatre”—co-signed and released a document titled “Principles for Building Anti-Racist Theatre Systems.” One of its purposes, as outlined in the opening statement, is to “[develop] a new social contract for our work environments that cares for and sustains our artistry and lives.”

Trouble in Mind was written in 1955, a time when the old “social contract”—the often implicit arrangements and expectations that govern the exchanges between individuals and institutions—was still in its infancy. A defining aspect of that old contract came from Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

A Quick History Lesson

I recently was shocked to learn that during the Great Depression, FDR’s administration developed an economic recovery program for Black American theatre.

Of course, theatre for and by Black Americans has a long history preceding the Great Depression. Roundabout has created an excellent, living document that outlines this history: a Timeline for Black American Theatre from 1821-1979.

FDR’s programs were called “Negro Units,” and they were a part of a larger initiative called the Federal Theatre Project.

One of the first all-Black American productions that received attention from white theatre-going audiences was produced by one of these so-called Negro Units. It was an all-Black, voodoo-themed Macbeth set in 19th-century Haiti.

The bold concept was controversial for both Black and white audiences. The production received mostly negative reviews from white theatre critics, who often panned the Black actors as being unable to perform Shakespeare’s work. The controversy certainly heightened national awareness for the production and for its young director—a 20-year-old Orson Welles, who would go on to become an iconic film director. A white man.

You see, Welles and John Houseman—a frequent collaborator of Welles’s, also a white man—were given authority over the New York Negro Unit in Harlem, though Black Americans were in positions of leadership at other Negro Units across the country. I guess the “powers that be” saw the value in putting Black men and women on stage; they just couldn’t grant Us the autonomy to be the architects of our own narratives.

In a 2019 piece for New York Times Magazine, Black theatre critic Wesley Morris refers to the theatre scene of New York as a place “where a mostly black audience is no guarantee, even for a black show.” Childress was grappling with this reality in 1955 when she wrote Trouble in Mind.

The circumstances in Trouble in Mind mirror the New York Negro Unit, with Black actors taking direction from a white director and writer for a play-within-the-play that is centered on Black characters.

41 years after Childress wrote Trouble in Mind, August Wilson was grappling with the same issues at the 1996 Theatre Communications Group national conference when he delivered a speech called “The Ground on Which I Stand”—his call to arms for the Black American theatre to take back Our stories and to establish a framework so that it can never be stolen again.

Wilson said, “For a black actor to stand on the stage as part of a social milieu that has denied him his gods, his culture, his humanity, his mores, his ideas of himself and the world he lives in, is to be in league with a thousand naysayers who wish to corrupt the vigor and spirit of his heart.” This is a problem that has persisted throughout the history of American theatre.

A Play Within A Play

Wiletta and the other characters in Trouble in Mind are working on a play called Chaos in Belleville. Oxford Reference states that a “play within a play” is “[a] dramatic convention popular in Elizabethan times, was a favourite with Shakespeare, who used it with great subtlety.”

Shakespeare uses the “play within a play” device to argue that theatre has the ability to reveal real world truths. You know the story: the character Hamlet stages a play in which a character performs the same murder he suspects his uncle of committing, in the hopes that seeing his uncle’s reaction will confirm his suspicions. Arguably, this is Hamlet at his most Extra.

In Trouble in Mind, Childress takes Shakespeare’s argument a step further by suggesting that the “play within a play” has the potential not only to reveal truths about our lived experience, but to inspire justice and change.

Trouble in Mind is a very intimate story. It isn’t reliant upon complex theatrics. The only head-spinning plot twists come from characters revealing their truest, deepest thoughts. Childress asks audiences to simply experience how the particular events of the play unfold through the eyes of a Black woman.

The character arcs of Wiletta and Manners, the white director, are evidence of Childress’s shrewd awareness of the play’s integrated audiences. It seems likely that a white theatre-going audience of the 1950s would identify with Manners as he and Wiletta come to blows. As I continued reading the play, I became frustrated with Wiletta as she was unable to connect to her character in the play within the play. Because we, as readers and audience members, don’t know the full text of the play within the play, Childress doesn’t allow us to get ahead of Wiletta’s final conclusion about the anti-Black and anti-feminist artistic choices being made by Manners and the unseen white writer.

Wiletta says of Chaos in Belleville’s playwright, “The writer wants the damn white man to be the hero—and I'm the villain.”

Anti-Lynching Plays

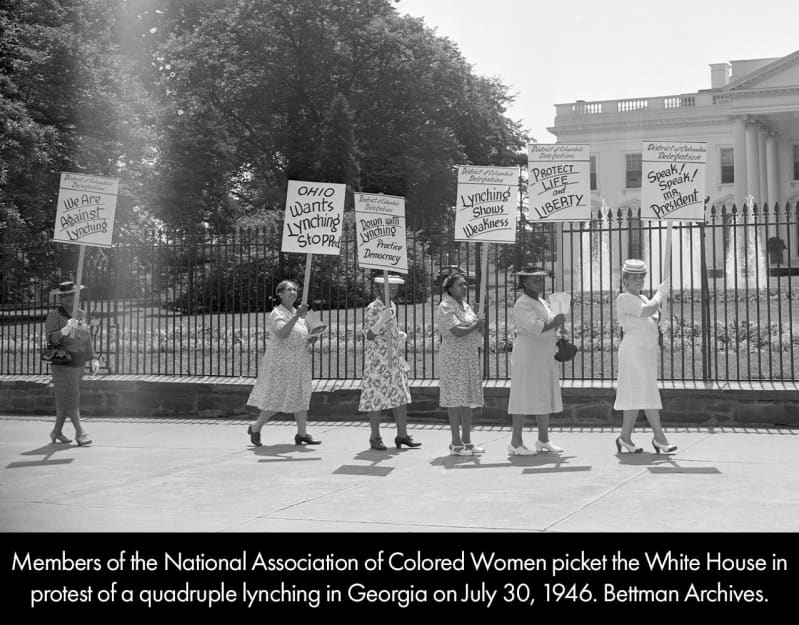

The play within Trouble In Mind—Chaos in Belleville—is an anti-lynching play.

Anti-lynching plays are a genre of drama invented by Black women playwrights in the late 1800s into the early 1900s as a form of protest against the ongoing lynchings of Black Americans throughout the United States, particularly in the South.

Moreso, they became a way for Black folks to investigate what was happening within the Black community and the Black family during the terrorism of white mobs and lynching in America in order to process and take action against further brutality.

Koritha Mitchell—a professor at The Ohio State University and author of the book Living with Lynching: African American Lynching Plays, Performance, and Citizenship, 1890-1930—gives a very clear definition of what she calls “lynching plays.” She references a 1998 anthology of “lynching plays” by Judith Stephens and Kathy A. Perkins when she says, “Even though a lot of writers talk about lynching or racial violence in their plays, it’s really when the lynching itself has a dramatic impact and shapes the plot.”

Many of the early anti-lynching plays were written as one-acts, so they could be published in Black publications and journals—like W.E.B. Du Bois’s Crisis Magazine—or read aloud in Black churches, living rooms, and schools.

One of the first anti-lynching plays—Rachel—was written in 1916 by Angelina Weld Grimké. It was recently presented as part of Roundabout’s Refocus Project Reading Series.

In Grimké’s Rachel, the title character delivers a monologue after her mother tells her a story recounting a lynching in the South:

Then, everywhere, everywhere, throughout the South, there are hundreds of dark mothers who live in fear, terrible, suffocating fear, whose rest by night is broken, and whose joy by day in their babies on their hearts is three parts—pain ... And so this nation—this white Christian nation—has deliberately set its curse upon the most beautiful—the most holy thing in life—motherhood!

In a speech delivered at the “The Negro Writer’s Visions of America” conference in 1965, Alice Childress also highlighted the particular plight of Black women, wives, and mothers in the face of the everyday threat of lynching for Black families. She said, “[The Negro mother] couldn’t tell her husband ‘a white man whistled at me, or insulted me, or touched me,’ not unless she wanted him to lay down his life before organized killers who strike only in anonymous numbers.”

Alice Childress carries the baton of the anti-lynching play genre in Trouble in Mind, but turns the genre on its head by having a fictional (and unseen) white playwright author Chaos in Belleville. Chaos in Belleville is a distinct departure from the anti-lynching plays of the late 1800s and early 1900s by Black women playwrights like Grimké in that the purpose of Chaos is to shock and tug at the heartstrings of the expected white Broadway audience.

Another marked difference between Chaos in Belleville and the original anti-lynching plays is that Chaos is written by a white man. This fictional white author of Chaos makes the choice to graphically depict the lynching of one of the play within the play’s characters—another major difference between Chaos and the true anti-lynching plays of the turn of the 20th century.

The Black women playwrights who created the genre were very aware of the mental health—though they may not have called it that at the time—of the Black artists and audience members of these plays. So, these women playwrights often wrote characters who talked about lynchings, rather than re-traumatizing their communities by staging the horrific act.

I am proud to be a part of another Black playwright’s version of the anti-lynching play. Mansa Ra is very clearly evoking the spirit of playwrights like Alice Childress and Angelica Weld Grimké in In the Southern Breeze. By writing this play with characters from different eras of American history, Mansa traces the history of lynching from its deep roots in American slavery to the public killings of Black folks happening in the 2020s, while staying true to the one-act form and particular care taken with regard to Black artists and audience members.

I am reminded that this work that we do as Black artists and educators, storytellers and truth seekers is so much more than it may seem. By honoring the stories that have come before us, we have the possibility to liberate those who come after us.

For me, Alice Childress has done just that.

I thank institutions like Roundabout Theatre Company and Rattlestick Playwrights Theater for taking our demands into account as we enter this new era of the American theatre. They have provided the space and resources for Black artists like me to continue in the footsteps of Alice Childress as architects of our narrative.

I only wish I could see what roles Wiletta would slay today.

REFERENCES

| The Combahee River Collective Statement. United States, 2015. Web Archive. Retrieved from the Library of Congress. Childress, Alice, Paule Marshall, and Sarah E. Wright. “The Negro Woman in American Literature.” SOS – Calling All Black People: A Black Arts Movement Reader, edited by John H. Bracey Jr., Sonia Sanchez, and James Smethurst, University of Massachusetts Press, 2014, p. 98 – 101. Grimké Angelina Weld. Rachel: A Play in Three Acts. 1916. Forgotten Books, 2012. Helen, Melissa. “Alice Childress' Wine in the Wilderness: A Harbinger of the Golden Era of the 1970s African-American Feminist Epistemology.” The Icfai University Journal of English Studies, vol. IV, no. 1, 2009. Kilson, Kashann. “The Forgotten Story of Orson Welles' All-Black 'Macbeth' Production.” Inverse, 16 Oct. 2015. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021. Asante, Molefi Kete. Foreword. Black Acting Methods: Critical Approaches, edited by Sharrell D. Luckett with Tia M. Shaffer, Routledge, 2017, p. xvi-xvii. Mitchell, Koritha. Living with Lynching: African American Lynching Plays, Performance, and Citizenship, 1890-1930. University of Illinois Press, 2012. Morris, Wesley. “Black Theater Is Having a MOMENT. Thank Tyler Perry. (Seriously.).” New York Times Magazine, 9 Oct. 2019. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021. Perkins, Kathy A. and Stephens, Judith L., editors. Strange Fruit: Plays on Lynching by American Women. Indiana University Press. 1998. "play-within-a-play." Oxford Reference. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021. “Rattlestick Playwrights Theater Presents our 2021-2022 Season.” Rattlestick Playwrights Theater. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021. “Shirley Graham Du Bois.” Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021. “We See You W.A.T.” We See You W.A.T. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021. Wilson, August. “The Ground on Which I Stand.” Theatre Communications Group Conference, 26 June 1996, McCarter Theatre Center, Princeton, NJ. Keynote Address. |