A Soldier's Play:

Designer Statements

Posted on: February 25, 2020

Derek McLane/Set Design

When I first read A Soldier's Play, I was totally absorbed by the murder mystery of it. Who killed Sgt. Waters? The play, of course, has bigger themes in mind, but that structure is very effective at grabbing your attention. For me, the play taps into a certain nostalgia for World War II — a war with far less ambiguous goals than more recent wars — and the patriotism I associate with it. That patriotism is the backdrop for every character in A Soldier’s Play, and the nostalgia I felt makes the racism the soldiers deal with that much more jarring. The play is very fluid in the way it is written. It jumps backward and forwards in time as various soldiers tell their story of the events surrounding the murder. Many scenes are simultaneously in an office and outside somewhere, as soldiers recount their last encounters with Sgt. Waters. So the play requires several different realities to co-exist, with both specificity and simplicity.

Members of the 2nd battalion, 25th Infantry, during the Louisiana maneuvers of 1941

After I read a play, I always start by doing some research. In the case of A Soldier’s Play, I looked a lot at WWII army bases, particularly in the south, where this takes place. I was struck by how simple they were. Virtually everyone was made of unadorned wood boards and beams; there was no decoration and simple construction. It is clear looking at the research the buildings were built quickly, and presumably not necessarily intended to last past the end of the war. Even senior commanders had very simple offices. And so I started sketching structures based on these images, to create a space simple enough and flexible enough that all of the many scenes could be contained with really minimal scene changes. From the sketches, I moved onto models—I usually make several different drafts—as I did here. Eventually, director Kenny Leon and I settled on the version that became the design. The last step in my studio was to draft the set —produce a set of scale drawings that a scene shop could use to build from.

Set model #1 by Derek McLane

I’ve done a pretty wide variety of shows with Kenny, from intimate plays to big television musicals, and I know how interested he is in bringing out the human side of every story and also in making every show feel that it is somehow of “today.” So my work with him on this was about putting us confidently in the America of 1944 and to do it in a way that also has the immediacy of 2020. My goal was to give it just enough detail that you feel WWII military base, and not so much that it feels fussy.

Set model #2 by Derek McLane

Dede Ayite/Costume Design

Suspense, thrill, sadness, and pride were emotions I felt as I read the last sentence in A Soldier’s Play. Written beautifully, I am honored to be a part of telling this story. A story that delves into the complexity of race in America. Although set during World War II, the heart of this piece feels just as significant for today. When I first read A Soldier’s Play, I was deeply intrigued by the sense of duty these brave men had that made them serve a country that did not recognize them as equals.

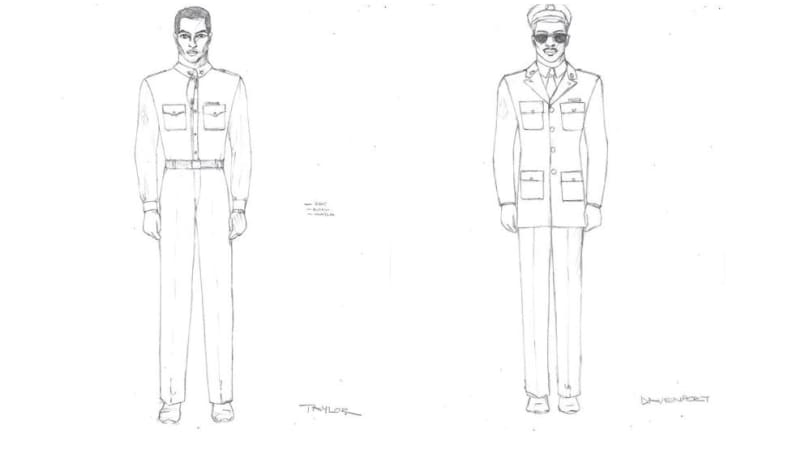

Costume sketches by Dede Ayite

Supporting this story with costumes, my first step was to identify the status of each character; identifying the rules and parameters that surrounded them in the army. A deep dive through historical material ensured accurate portrayal of the uniforms they would have worn during this time. Speaking with people who have in-depth knowledge of the time we are aiming to represent on stage is always a crucial point to get the most accurate sense of the period. The next step for me was to then identify their individual journeys through the play, noting what makes them different from each other. How their personalities, backgrounds, and sense of self might affect the way a character is presented.

Yet another helpful part of the process was to sit with the rest of the design team and the director, Kenny Leon, to discuss how we want to manifest this story. Collaboration is key here — in order to create a world that feels seamless. Hearing various viewpoints and approaches surely enriches the process and final product. The next step for me after gathering enough information will be fittings with the actors playing the various roles. This is vital, as the uniform pieces and costumes don’t become real until there is a human being wearing them. Here the pieces start to take form. Ultimately, the individual pieces begin to tell a story that adds depth and specificity to the character wearing them.

Warner Miller, Nnamdi Asomugha, and Blair Underwood

© Joan MarcusAllen Lee Hughes/Lighting Design

I designed the lighting for the original production of A Soldier’s Play directed by Douglas Turner Ward at The Negro Ensemble Company (NEC) in November of 1981. The first time I designed lighting for this play, I thought of it as a “whodunit” — and it still is a “whodunit” because the opening scene is a murder, which is the first thing the audience sees happening on stage. But this time around the play has different resonance, I believe, because of Sergeant Waters’s disturbed state of mind and recent race-inspired crimes that have occurred in our country. This is an African American story that speaks to me as an African American man, especially in this day and age — when we see so-called “good people” acting in questionable ways.

My job as lighting designer is often to bring together the set and the costumes in terms of how they are lit and the colors I choose. Once I speak to the director and I receive samples of the costume fabrics and renderings of the set, I find a complementary color palette. With A Soldier’s Play, I also have to decide how to use the lighting to delineate scenes that are taking place in the past as opposed to those taking place in the present. I will be using backlight and color to highlight the scenes in the past. I also will be using a technique called selective visibility, so the audience isn’t aware of who is using the gun in the opening scene. The entire action of the play takes place at Fort Neal in Louisiana in 1944, and that location requires specific color choices as well. Kenny Leon, the director, has asked that the heat and humidity of that area be reflected in the lighting, and it is my job to make that happen.

Dan Moses Schreier/Sound Design

This powerhouse of a play has personal resonance for me as someone who grew up in Detroit, Michigan in an integrated neighborhood and who went to integrated schools. The play deals with racial politics of the segregated United States Army during World War II and very skillfully delineates attitudes towards race in the entire country at the same time. The first thing I have to do is read the play over numerous times and jot down my thoughts, and then I meet with the director. My initial meetings with director Kenny Leon have been about how to best evoke the time period and themes of the play in terms of the music choices we make.

The original script calls for the play opening with the Andrews Sisters recording of “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree,” but Kenny and I have been looking into using a recording by Son House, who was an American delta blues singer and guitarist, noted for his highly emotional style of singing and slide guitar playing in the 1920s, ‘30s, and ‘40s. In fact, his work was rediscovered by the late Alan Lomax, who spent almost 70 years as a folklorist and ethnographer, collecting, archiving, and analyzing folksongs and music in America. In addition to music, this play literally starts with a bang because the first thing after music — sound-wise — is a gunshot, but so far we haven’t decided whether those shots will be live ammo or recorded.

As sound designer, I am not only responsible for music and all the necessary ambient sound, I am also in charge of how best to hear the actors in a space that has tricky acoustics. So, I will be making decisions about the best way to mic actors subtly, so that everyone in the audience can hear them.