The Refocus Project: Year One:

On "Wedding Band: A Love/Hate Story in Black and White" by Alice Childress.

Posted on: April 7, 2021

1.

| Summer 1918… Saturday morning. A city by the sea… South Carolina, U.S.A |

Charleston, SC. The setting of Alice Childress’ Wedding Band: A Love/Hate Story in Black and White. Alice Childress’ birthplace. And my second hometown. Where - in my African-American Theater Studies class at the College of Charleston – I pored over works by August Wilson, Ntozake Shange, Lorraine Hansberry, Douglass Turner Ward, Amira Baraka, Adrienne Kennedy, and so many others. Extraordinary theater artists who would all have lasting impressions on writing. But, Alice Childress, quite literally, met me where I was.

The College of Charleston’s Simons Center for the Arts sits on St. Phillips Street between George and Calhoun Streets. Calhoun Street serves as a main artery into Downtown Charleston and functions as a reference point when navigating one’s way across campus. As a student I walked countless miles along Calhoun from dorm rooms to shops to classes and back again. And past the statue of the street’s namesake as it welcomed students, visitors, and locals alike to Charleston’s Downtown Historic District from Marion Square. Needless to say, John C. Calhoun’s legacy looms large over Charleston. And Alice Childress understood his white supremacist legacy as foundational to the tensions that have lingered in the Lowcountry long after his death. Those tensions are the foundation on which Childress builds her “Love/Hate Story in Black and White.” And it is this “Love/Hate” relationship with the American South that would prove foundational to my own brand of storytelling.

2.

There are a number of reasons why I chose to do my undergraduate studies in Charleston. The arts scene, for one. The queer scene for another. Charleston was that blue dot in a sea of red where I could “find myself.” And, not only was it both close enough to home (in Columbia, SC) to call for a lifeline when I needed one and far enough away from home to practice some sort of independence, Charleston was - above all - stunningly beautiful. Its romantic landscape and architecture housed the stories of so many ghosts. Stories abbreviated on historical markers and along carriage tours. But, fully detailed in truths whispered among those descendants of slaves who made up the town. Truths crested just above the surface like cobblestones that line the town’s winding narrow streets; making them hard to navigate. Truths at war with a tourist industry built on the altering and softening of history. Truths in each gentle blade of sweetgrass made more resilient in their weaving. Charleston, in so many ways, a beauty labored into existence by Black hands.

Charleston’s beauty stands in stark relief to its violent past. One born out of the other, it is impossible to tell the story of Charleston without this juxtaposition. And, it is impossible to understand the American South without acknowledging both that juxtaposition and the carefully constructed divisions placed between poor whites and the descendants of slaves. (See John. C. Calhoun). Whereas wealthy slave owners and their heirs never questioned what of Charleston belonged to them, Blacks and poor whites were left to fight their way into narratives never intended for their inclusion. With poor whites feeding off the crumbs of white supremacy to do so. Wedding Band, at first glance, reads as a story of forbidden love. Julia (a Black seamstress) and Herman (a white baker) are unable to marry legally or love freely in a relentlessly racist world. But, look deeper and it becomes a story of ownership.

| HERMAN: | My father labored in the street…liftin’ and layin’ down cobblestone… liftin’ and layin’ down stone ‘til there was enough money to open a shop. …We were poor…No big name, no quality. |

||

| JULIA: | Poor! My gramma was a slave wash-woman bustin’ suds for free!...We the ones built the pretty white mansions…for free…the fishin’ boats…for free…made your clothes, raised your food…for free…and I loved you-for free… …If it’s anybody’s home down here it’s mine…everything in the city is mine—why should I go anywhere…ground I’m standin’ on—it’s mine. |

Dig deeper and the question becomes “whose story of this American South gets to be told?”

| JULIA: | …all the dead slaves…buried under a blanket-a this Carolina earth, even the cotton crop is nourished with heart’s blood…roots-a that cotton tangled and wrapped ‘round my bones. | ||

| HERMAN: | And you blamin’ me for it… | ||

| JULIA: | Yes!...For the one thing we never talk about…White folks killin’ me and mine. You wouldn’t let me speak. …It hurt me not to talk…what you don’t say you swallow down… |

3.

Like Childress my initial goal was to “make it” as an actor in New York City. Graduate school had mostly trained my South Carolina accent away. And when I did access it for auditions, I was often asked to substitute my authentic voice for a more palatable “general southern” sound. I watched with curiosity at depictions of a “General South” that was totally unrecognizable to me. A South that could hold Herman’s story, but made little room for Julia’s. The American theater’s “South” served mostly as a scapegoat for the nation’s ills. Wedding Band, by contrast, reflected America; Police brutality. Racial inequality. Global pandemic. (1918 meet 2021.)

Rarely used was the nuanced brush that Childress painted her Black Charlestonians with in Wedding Band. Julia’s autonomy and ferocity rocked me to my core upon reading. Her neighbors (Fanny, Mattie, Lula, and Nelson) were as familiar to me as the folks outside my door; challenging, complicated, and gloriously imperfect. Each holding phenomenal stakes in this South they helped build. Ownership of place. Ownership of story. That’s what Childress gave me. Every seed of my Black Queer Artist existence was set in the “Carolina earth.” Alice Childress challenges me to write with a mandate to specificity. To write my Southern truth. Not so as to absolve the South, but to unpack the harder thing…the loving it.

“Carolina water is sweet water…Wherever you go you gotta come back for a drink-a this water. Sweet water, like the breeze that blows ‘cross the battery…” - (Julia) Alice Childress ♦

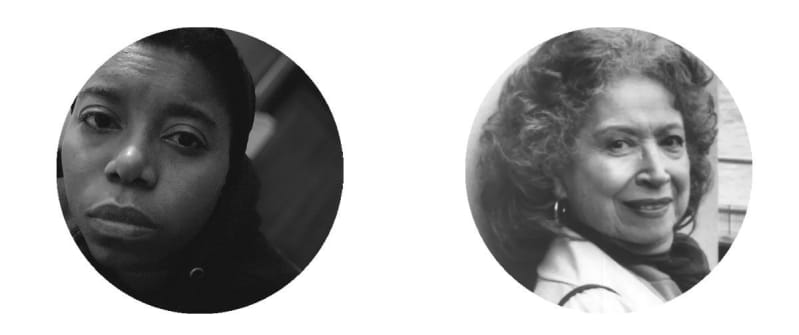

DONNETTA LAVINIA GRAYS is a Brooklyn-based playwright from Columbia, SC. Plays include Where We Stand, Warriors Don’t Cry, Last Night and the Night Before, Laid to Rest, and The Review or How to Eat Your Opposition among others. Donnetta is a Lucille Lortel, Drama League, and AUDELCO Award Nominee. Recipient of the Helen Merrill Playwright Award, NTC Barrie and Bernice Stavis Playwright Award, Lilly Award, Todd McNerney National Playwriting Award, and is the inaugural recipient of the Doric Wilson Independent Playwright Award. She holds commissions with Steppenwolf, Denver Center, Alabama Shakespeare Festival, WP Theater, and True Love Productions.

ALICE CHILDRESS (1916 - 1994) was a playwright, novelist, and actress. Other works include the plays Florence (1949) and Trouble in Mind (1955), and the film A Hero Ain't Nothin' but a Sandwich (1978).