Vamping in the 'Sunday' Score

Posted on: March 22, 2020

In my previous post, we spent some time discussing the ways that scene changes are a unique part of the fabric of live performance, and how music can be used to smooth over the bumps in our experience that would interrupt our suspension of disbelief.

In the following posts, we will look at several examples from Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine’s Sunday in the Park with George to begin to uncover the different ways scene change music can be used to help tell a story. Sondheim’s scores are meticulously composed, and he frequently ties storytelling content to specific musical figures that evolve in tandem with the story, making a score like Sundayin the Park with George a particularly useful place to start.

Perhaps the most unique quality of scene change music is that, usually, it is written to be repeated an unknown number of times. If a scene change takes longer in performance than rehearsed (an actor unexpectedly becomes ill, a set piece is accidentally broken, someone has misplaced a vital prop) and the scene change music comes to completion before the performers are ready to continue, we’ll be left waiting in silence, instantly alerted to the fact that something is amiss. But if the music can continue playing indefinitely, we remain placated for much longer. For this reason, a great deal of scene change music is written to have a vamp—or a section of music that can be repeated indefinitely as needed—usually at the end of the song.

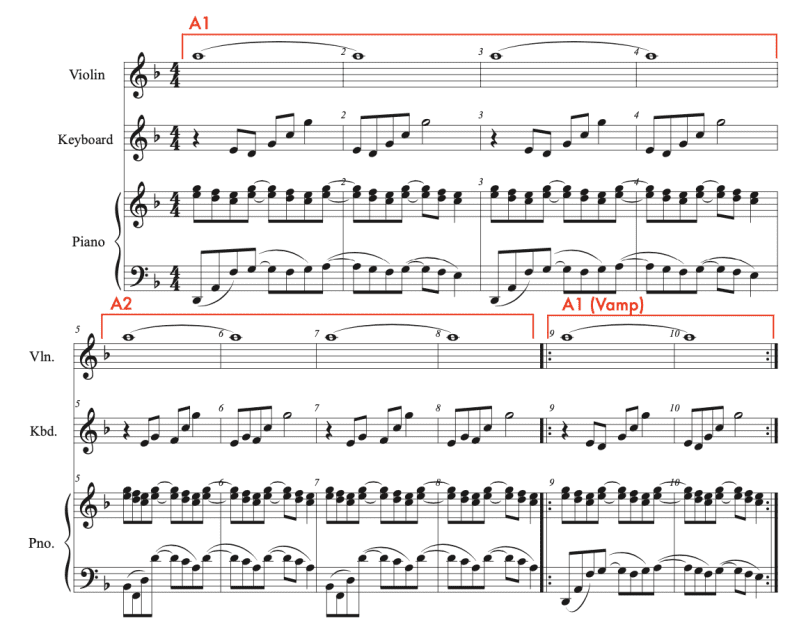

Figure 1, "Scene Change to Studio" from Sunday in the Park with George, divided into sections.

Figure 1 (above) is a reduction of a song from Sunday in the Park with George called “Scene Change to Studio.” It is played towards the beginning of the first act, aptly underscoring the scene change leading to a scene set at Georges’ art studio where he and Dot sing the song “Color and Light.”

The song is short, and simple enough: the piano plays what we can refer to as the “moving thirds” theme, a musical figure that occurs several times throughout the show, ultimately becoming the accompaniment for the song “Finishing the Hat” later in the first act. The keyboard outlines the same two arpeggios that begin the opening song in the musical (these arpeggios are also used frequently as fanfares and musical stings throughout the score). And the violin is playing a single high sustained note, anchoring the piano and keyboard parts that are both so full of movement, and supplying a bit of tension as we drive towards the next scene.

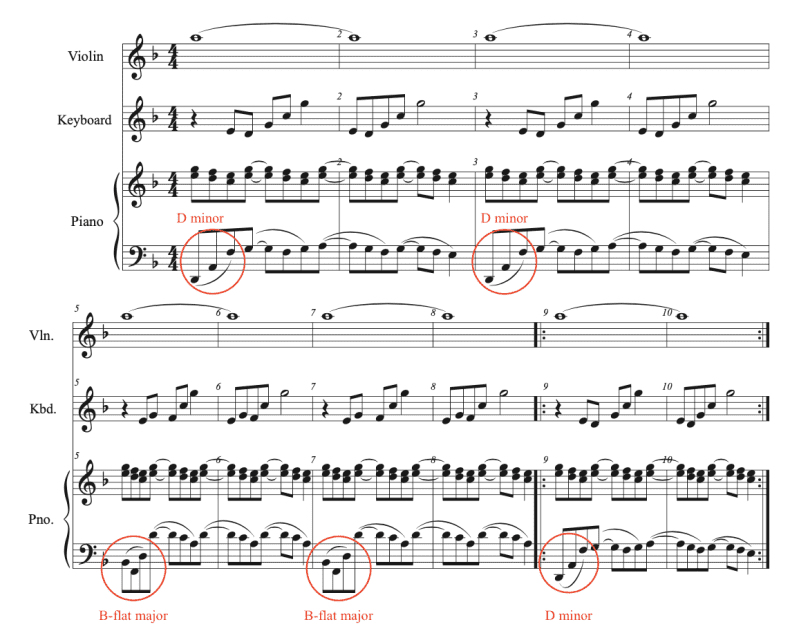

We can break this song down into three sections: A1, A2, and A1 (Vamp), annotated in figure 1 above. (You’ll notice listening to them that the A1 sections sound identical.) We can call them all A because they all contain the same component parts previously listed, just with slight variations. In figure 2 (below), we can see how in the A1 sections, the lower piano part begins by outlining a D minor chord, contextualizing those sections in a D minor sound. This lends a softer, more reflective quality to the music. In the A2 section, the lower piano part changes to outline a B-flat major chord, recontextualizing the rest of what we hear with a brighter B-flat major sound. In combination with the violin sustaining an A—a note that falls harmoniously within D minor, but that sounds very dissonant on top of a B-flat major chord—the A2 section carries quite a bit more tension than the A1 section.

Figure 2, "Scene Change to Studio" from Sunday in the Park with George, with chord changes annotated.

Ultimately, having gone on a journey from a place of rest in A1 to a place of tension in A2, we return to a place of rest in a shortened version of the A1 section. We can call it “A1 (Vamp)” because it is written to repeat until the scene change is finished and the conductor receives their cue to continue to the next song. Vamp sections are written intentionally to be loopable—that is, the end of the vamp leads seamlessly back to the beginning of the vamp. This is so we are not alerted to each new repetition, resulting in a composition that sounds coherent in performance, but can also respond and adapt in the moment to the immediate needs of the production. As soon as the scene change is completed, the conductor receives their cue to continue, and they in turn signal to the orchestra to conclude the song.

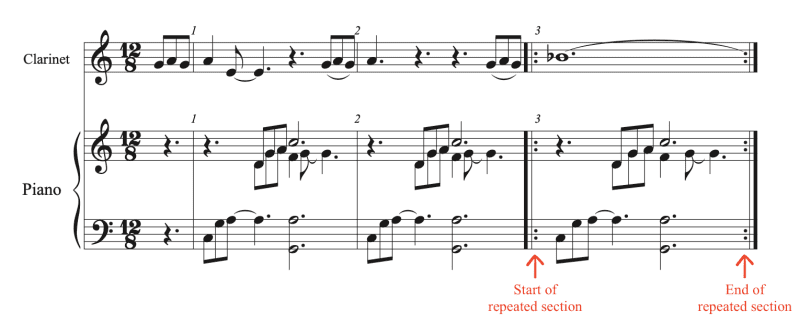

Figure 3, "After Children" from Sunday in the Park with George

Figure 3 (above), a reduction of a song called “After Children,” is played during the scene change immediately following “Children and Art,” a song late in the second act that Marie (Georges and Dot’s now-elderly daughter) sings to George (Marie’s grandson). During the song, she offers him comfort and wisdom that the only things of real value we leave behind after we die are children and art. Immediately following, Marie is wheeled off-stage, and we transition to a scene where George returns to the park from the first act to meet his past and wrestle with his insecurities as an artist. The music played during this transition is a direct quote from “Children and Art,” the clarinet in “After Children” playing the melody previously sung by Marie on the lyrics, “He should be happy / Mama he’s blue / What do I do?” and “You would have liked her / Mama did things / No one had done.”

This song is much shorter than the first example, consisting of just a single musical phrase. (We can gather that this scene change probably took much less time to complete than the one covered by “Scene Change to Studio.”) But it’s built similarly in that brings back musical material we’ve heard before and concludes with a vamp. In “After Children,” the vamp section (the beginning and end of a repeated section in music is signified by double dots, annotated above) is just one measure long, repeating the same accompaniment figure in the piano that appears throughout the song “Children and Art,” and holding the sustained B-flat in the clarinet. This B-flat a borrowed note outside the song’s key, so it carries an unexpected, slightly surprising quality, hanging in the air like a question. What will George do?

As we can see, these songs exist first for their utility. They are made intentionally to stick around exactly as long as it takes for everything to get into place on stage, and no longer. But if we look beyond their structure, we can see that there’s also an impressive amount of dramaturgy compacted into these songs. The curated re-introduction of particular themes during these shifts bring to mind the places in the story where we’ve previously heard them, guiding us to consider certain plot points as we move towards the next part of the story. (We will discuss in the next post how the “moving thirds” theme played during “Scene Change to Studio” comes to represent something deep and complicated at the heart of Georges and Dot’s romantic relationship, and how hearing it during this (and one other) scene change helps to codify that relationship between music and story.) And listening to that fragment of melody from “Children and Art” during “After Children” encourages us to reflect on those sentiments that were previously accompanied by that same music: how there is a lineage that connects “every artist [to] everybody who’s ever painted a picture” (as Sondheim put it in a 1990 interview with David Savran). How we ultimately connect or fail to connect with that lineage, with our loved ones, with our purpose in life, and how making those connections helps us to forge a path forward.

Whether or not George will consummate those connections hangs in the balance during the “After Children” scene change. So, as we listen to that melody, waiting for the next scene to begin, we do indeed wonder: what will George do next? And we know we’re about to find out—but not until the music stops playing.

Columbia@Roundabout is a collaboration between Columbia University School of the Arts and Roundabout Theatre Company which provides exceptional educational and vocational opportunities for the next generation of playwrights and theatre practitioners.

The program includes an annual reading series for Columbia MFA students, Teaching Artist training facilitated by Education at Roundabout and two fellowship positions in Roundabout’s Archives.

As a part of the Archives fellowship, the MFA candidates conduct deep research into our historic records and are encouraged to produce scholarship that explores Roundabout’s contribution to American theatre. Josh Brown is one of the Archives Fellows, and over the course of the coming months, he will write a series of articles about interstitial music from Roundabout’s musical productions.