Set in 1846, El Corrido de California portrays the experience of the Segura family of Californios (the term for Spanish colonists and early settlers of California) as they face the impending invasion by the United States. Although California still belonged to the Mexican Republic, local leaders like Don Gerónimo Segura, an alcalde (a local mayor/judge) had autonomy. To understand the characters and the events of the play, it is helpful to consider California’s relationship to Mexico and the US at the time, and the forces driving the national conflicts in the background of the play.

Jump to:

In the early 18th century, revolutionary ideas about democracy and independence were rising around the world. Miguel Hidalgo Y Costilla, known as the founding father of Mexican independence, was inspired by these ideas. Costilla found support from the middle-class Criollos (the Mexican-born offspring of the upper-caste Spaniards), as well as a few former royalist army officers. The efforts seeking independence for Mexico became known as La Conspiracion de Queretaro (The Queretaro Conspiracy).

Costilla began Mexico’s fight for independence at midnight on September 16, 1810. The War of Independence lasted 11 years, during which revolutionary heroes Hidalgo, José María Morelos y Pavón, and Vicente Guerrero mobilized the Indian, Mestizo (people of mixed Spanish and Indigenous descent), and enslaved Black populations into the war effort by invoking the ideals of civil rights and racial equality.

In 1813, Morelos summoned the first independent congress and issued Los Sentimientos de la Nación (The Feelings of the Nation). In it, Morelos declared that the Americas should be free from monarchies, governments should emanate from the people, and all laws should be discussed in congress and affirmed by popular vote. The document recognized equality for all people and abolished caste distinctions, torture, and, significantly, slavery. Morelos, a mixed-race leader with Black, Indigenous, and European heritage, attempted to gain US President James Madison’s support for Mexican independence, which he argued pursued the same ideals as the American revolution. But American leaders were alarmed by Mexico’s looming abolition of slavery, particularly at a time when rebellions of Blacks and Native Americans in Spanish Florida seemed to pose a threat to white dominion in America.

Mexico formally declared its independence in 1821 and was promptly recognized by neighboring countries in South and North America as an independent nation.

Mexico was a large country. It included Texas and the land now known as New Mexico, Utah, Nevada, Arizona, California, and part of Colorado. During its first years as a republic, Mexico experienced huge political instability, including various attempts at reconquest by the Spanish Crown, the first French intervention (which was partly subsidized by the United States), and many political disagreements between liberal and conservative groups, all of which left the country politically and economically vulnerable to the US invasion.

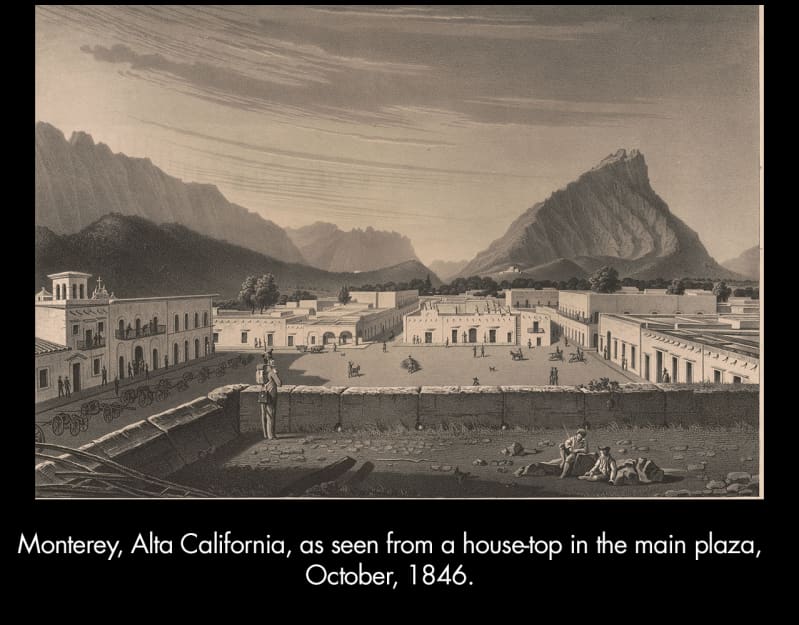

The large territory known as Alta California in 1846 encompassed land across today’s California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Arizona, Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico. The earliest Spanish settlers came to California in the late 17th century, traveling northward from Mexico. Spain established a series of presidios (military forts) along California’s coastline, and created a system of Franciscan-run missions to exert control over the native population. Small towns or pueblos developed around the missions and presidios. The Spanish crown maintained control over its California territory by giving provisional land grants to select civilians (though technically the monarchy still owned the land). An alcalde, a local mayor/judge who governed over the pueblos, was appointed to serve as representative of the crown.

About 25 years before El Corrido de California begins, Alta California experienced a period of growth and independence. Under the new Mexican Republic, the mission properties were removed from the Franciscans. The land was re-granted to Mexican citizens, and for the first time, to select foreigners who swore allegiance to Catholicism. These grants were no longer subject to government control, so more land became privately owned.

A new economy built around rancheros (cattle ranchers) like the Segura family took hold along the coast, with beef and cow hides as the key commodities. Californios now had much more freedom to trade with foreigners than under Spanish rule, and merchants from Britain, Canada, France, and the United States became part of the economy. John Sutter, a German-born businessman, arrived in San Francisco in 1839 and established a large fort, which would be a stopover for the white settlers who were now entering California from the Oregon border. Many of these settlers were trappers and hunters, as well as sailors who arrived in San Francisco and stayed. It took just a few years for the new white settlers to grow resistant to Mexican authority, leading to the 1846 Bear Flag Rebellion (see below).

Alta California was organized into two districts. The larger population inhabited the Southern towns: Los Angeles, San Diego, and Santa Bárbara (the setting of the play), while the northern, less-populated district included the towns of San Luis Obispo, Puerto de Monterey, San Francisco, and Sonoma. The alcaldes remained important local rulers. Living far from the capital in Mexico City, Californios grew resistant to intervention from the central government. The last Mexican-appointed governor, Manuel Micheltorena, was so unpopular that the Californios rose up in revolt. He fled in 1845, and the Californios appointed native-born Pio Pico, a local ranchero with African heritage, as their governor. Californios thus obtained unofficial home rule, the ability to govern themselves, for a short time before the US invasion.

The term “Manifest Destiny” was used for the very first time in 1845 by John L. O’Sullivan in a pitch for the annexation of Texas to the US. The term conveys the idea that imperialistic expansion was the God-given right and the destiny of the US. This idea justified several expansionist wars, including the invasion of Mexican territory in 1846, which permitted the forced acquisition of what is now known as the Southwest.

The term has its basis in “Anglo-Saxonism,” a racial belief that emerged in Britain in the 1500s, asserting the specifically Anglo-Saxon superiority of the Caucasian race, and that was revived with aggressive nationalism by American intellectuals in the 19th century. This belief conveys a conviction that “inferior peoples” must not only assimilate to the “superior institutions'' but must ultimately be exterminated. The same Anglo-Saxons classified the “inferior peoples” and racialized any group that stood in the way of their imperialistic expansionism. Thus, the concept of “Manifest Destiny” was used to justify slavery in the south, and the removal or genocide of Native Americans in the West.

After its independence, Mexico abolished slavery, providing a safe haven for many enslaved people from the US. This created tension between the U.S and the Mexican governments. In 1826, the US tried to negotiate a treaty with Mexico for the surrender of fugitive slaves that might attempt to escape to the Mexican Republic, but the Mexican Congress denounced slavery and rejected the treaty.

In the years preceding the war with Mexico, debates raged over the role of slavery in US foreign policy. The desire for the aquisition of the Mexican territories was meant to “tip the scales” in favor of slave-owning states. In 1836, John Quincy Adams stood up in Congress to denounce Texas’s fight for independence as “a war between slavery and emancipation, (in which) every possible measure has been made, to drive us into the war, on the side of slavery.” Adams praised the abolitionist sentiments of the Mexican people, while exposing the aggression of the Anglo-Saxon expansionist values of the white settlers against Blacks, Seminoles, and Mexicans.

Before and during the Mexican-American War many abolitionist newspapers denounced the American expansion to the west as a means to expand the institution of slavery, while praising the Mexican values of equality and liberty for all. In a letter published by the National Anti-Slavery Standard in 1847, Frederick Douglass critiziced the US goverment and exposed its real intentions for the acquisition of the West:

The real character of our Government is being espoused…. The present administration is justly regarded as a combination of land-pirates and free-booters. Our gallant army in Mexico is looked upon as a band of legalized murderers and plunderers. Our psalm-singing, praying, pro-slavery priesthood are stamped with hypocrisy; and all their pretentions to a love of God, while they hate and neglect their fellow-man, is branded as imprudent blasphemy.

El Corrido de California takes place in 1846, against the background of a war already in motion. US President James K. Polk based his 1844 campaign on a message of manifest destiny and the importance of acquiring all lands across the North American continent. Specifically, Polk set his sights on territory in southern Texas and all of Mexico’s Alta California.

Some of the earliest tensions between Mexico and the United States focused on Texas. White Anglo settlers flooded into Texas soon after the Mexican independence, and soon outnumbered the Spanish-speaking Tejanos. These Anglo settlers brought aspirations for both a democratic government and a slavery-driven economy. In 1836, they rebelled against the Mexican government and declared an independent “Lone Star Republic.” In the Velasco Treaty, Texas guaranteed to Mexico that it would not join the US, but in 1845, it joined the union as a slave-holding state.

One of Polk’s first acts as President was to order US troops to occupy the area on the Rio Grande—150 miles south of the border Mexico had initially negotiated with Texas as part of its independence. Prior to any overt military aggression, this occupation was perceived as a provocation, both by Mexicans and by American opponents of Polk’s expansion policy.

Polk sent John Slidell, a Congressman and supporter of his goals, to Mexico with an offer to settle the Rio Grande as Texas’s southern border for $3.25 million, and to purchase California for $3 million. Mexico rejected Slidell’s diplomatic credentials and his purchase offers, which gave Polk the basis he needed to discuss a declaration of war with his cabinet. Soon afterwards, Mexican troops attacked a unit of American soldiers in the disputed Texas border territory, and Polk officially declared war against Mexico in May, 1846.

While much of the war was fought on land in Northern Mexico, primarily around the Rio Grande, Polk’s key objective was the conquest of California. Conflict between the Californios and the white settlers was brewing even before news of the war reached California. The rebellion of white settlers known as the “Bear Flag Rebellion” set the stage for a full-scale conquest by the US. In February 1846, the unannounced arrival of US Captain John C. Frémont and a troop of 60 American soldiers, claiming to be on a scientific expedition raised Mexican suspicions. In April of 1846, José Castro, the governor of Alta California, threatened to revoke the land grants previously issued by Mexico to some American settlers. The settlers asked Frémont to aid their cause, and though he initially claimed neutrality (while encouraging resistance), he and his troops joined their armed rebellion in June. Frémont and the American rebels captured the town of Sonoma, then moved south to take a poorly-armed Mexican fort near San Francisco. They declared an independent California Republic and raised a flag bearing a single star and the image of a grizzly. The independent republic lasted mere weeks, but it paved the way for the US to challenge Mexico’s claims to California. The rebels soon learned that America was at war with Mexico, and when an US battleship arrived at Monterey Harbor, Frémont and his men enlisted in the official US military operations.

Over the next two years, US troops conquered Northern Mexico from three directions: from southern Texas, moving southward into the Mexican state of Monterrey; from New Mexico moving west to California; and along the California coastline, aided by the US Navy. In Northern California, most of the Californios submitted without resistance to the US; however many Californios perceived the Americans as unjust invaders and took a stand to fight for their land. In September 1846, a small group of Californios drove US troops out of Los Angeles and took back control of the town. The Americans retreated, and for about six months, Californios held control of its southern district, including Santa Bárbara and San Diego. The Mexican government, facing attacks from the US on multiple fronts, was unable to provide more support; however, the Californios held their ground against the US until they were eventually outnumbered and defeated in January 1847. In Apuntes para la historia de la guerra entre México y los Estados Unidos (Notes on the History of the War between Mexico and the United States), published in 1848, a contemporary Mexican historian wrote:

This was the last effort that the children of California made in favor of the freedom and independence of their country, whose defense will always do them honor, because without resources, without elements and without instruction, they launched into an unequal struggle, in which more than once they made the invaders know what a people can do when it fights in defense of its rights.

El Corrido de California demonstrates the nationalism and pride that motivated Californios’ resistance. It also offers a critical portrayal of some of the actual Americans who would be instrumental to the conquest of California, including Navy Commodore Robert Stockton, Lt. Archibald Gillespie, and the wealthy trader Abel Stearns.

The war continued until February 1848, when Mexico surrendered and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed. Although Polk served only one term, he accomplished all of his objectives to expand the US’s hold on the continent. Despite the calls by some Americans to seize all of Mexico, the US ended up with about half: including all of California and New Mexico, and the expansion of Texas to the Rio Grande. Polk had given little heed to how the slavery debate would escalate as the nation nearly doubled in size as it expanded to the West—thereby escalating a conflict that would lead to the Civil War. In the newly conquered California, Mexican thinkers and journalists continued to express their criticism against slavery, denouncing the US's attempt to expand slavery in Latin America.

El Corrido de California ends with the words of South Carolina Senator John Calhoun during the debate over the treaty. A defender of slavery and soon-to-be leader of Southern succession, Calhoun opposed aquiring Mexican land because he feared the increase of non-white American citizens. At its heart, El Corrido de California gives voice to the identity and history of the Mexican-American people: portraying the pride with which the Californios fought for their rightful place on their own lands, and honoring their role as original inhabitants of the Southwestern territory.

The Mexican corrido is oral storytelling, usually in song form. It reached its peak in the first decade of the 19th century during the Mexican revolution. The origin of the corrido is a polemical topic among Mexican scholars. Some relate the genre to the Spanish Romance, an oral and literary tradition characteristic of the Iberic and Spanish regions. Others relate it to indigenous Pre-Hispanic oral traditions. Still others believe that the corrido is a result of mestizaje, the blend of Spanish and indigenous cultures. Corridos often focus on epic, political, and historical events, but many of them also tell the stories of everyday hardships of working class people. Throughout history, this musical expression has served as a source of information and has been used for educational purposes.

After the Mexican-American War, corridos were popular among Mexicans in the newly conquered California, serving a similar function to that of the blues in Black American culture. They provided a common way for Mexicans to build community and to find identity. Today, corridos continue to be well-liked among Mexican and Mexican-American communities, evolving throughout the years to accommodate different musical trends and subgenres. An example of an original corrido written just after the Mexican-American war can be heard here.

REFERENCES

|

Barreiro, Alejo, et al. Apuntes para la historia de la guerra entre México y los Estados Unidos. Translated by Ana Cantoran Viramontes, edited by Alcaraz, Ramón, México, Tip. de M. Payno hijo, 1848. “Bear Flag Revolt, June 1846.” Golden Gate National Recreation Area California. National Park Service. 28 February 2015. Chávez, Ernesto ed. The U.S. War with Mexico: A Brief History with Documents. Bedford/St. Martin's, 2008, pp 118-120. Creason, Glen. “CityDig: Border Problems of the 19th Century.” Los Angeles Magazine. 16 September 2015. “Early California History: An Overview.” COLLECTION: California as I Saw It: First-Person Narratives of California's Early Years, 1849 to 1900. Library of Congress, ND. Grivas, Theodore. “Alcalde Rule: The Nature of Local Government in Spanish and Mexican California.” California Historical Society Quarterly, vol. 40, no. 1, 1961, pp. 11–32. “HISTORY: Fast Facts on Alta California.” Los Californianos. 2021. Accessed 18 July 2022. “John Slidell.” A Continent Divided: The U.S.-Mexico War. Center for Greater Southwestern Studies, UT Arlington Library Special Collections, 2022. “La Conspiración de Querétaro (1810).” Secretaria de la Defensa Nacional, Gobierno de México, Momentos Estelares. “La Revolución Mexicana y los Estados Unidos.” COLLECTION: México de la Independencia a la Reforma, 1800-1857. Library of Congress. “209 Aniversario de la independencia de México.” Biblioteca de Publicaciones Oficiales del Gobierno de la República. 13 September 2019. “Las Revoluciones de México. El Proceso Independentista de México.” Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de las Revoluciones de México, 2015. Porrúa, Miguel Angel. Documentos para la Historia del México Independiente 1800-1938. Editorial, Porrua, 2010, pp. 290-306. “Federalismo y Centralismo.” Portal Académico Universidad Autónoma de México. “The Myth of Manifest Destiny.” Jstor Daily. 5 May 2002. Robert C. Bannister. (1982). "Review Of "Race And Manifest Destiny: The Origins Of Racial AngloSaxonism" By R. Horsman." Pennsylvania Magazine Of History And Biography. Volume 106, Issue 2. 309-310. “Speech of John Quincy Adams on the Joint resolutions for distributing rations to the distressed fugitives from indian hostilities in the states of Alabama and Georgia, 1836 May 25.” Keith Read, Hargrett Rare Book and Manuscript Library, The University of Georgia Libraries, Digital Library of Georgia. Ortiz, Paul. An African American and Latinx History of the United States. Beacon Press, 2018, pp. 33-53. Pinheiro, John C. “James K. Polk: Impact and Legacy.” Miller Center, UVA, 26 June 2017. “REMEMBER THE ALAMO: The Republic of Texas.” American Experience. PBS. ND. “Sentimientos de la Nación.” Orden Jurídico, Constitución de 1813, Gobierno de México. “The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.” Hispanic Reading Room, Hispanic Division. The Library of Congress, 9 Mar. 2022. “War In The West.” A Continent Divided: The U.S.-Mexico War. Center for Greater Southwestern Studies,UT Arlington Library Special Collections, 2022. Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: Harper & Row, 1990, pp 149-169. |