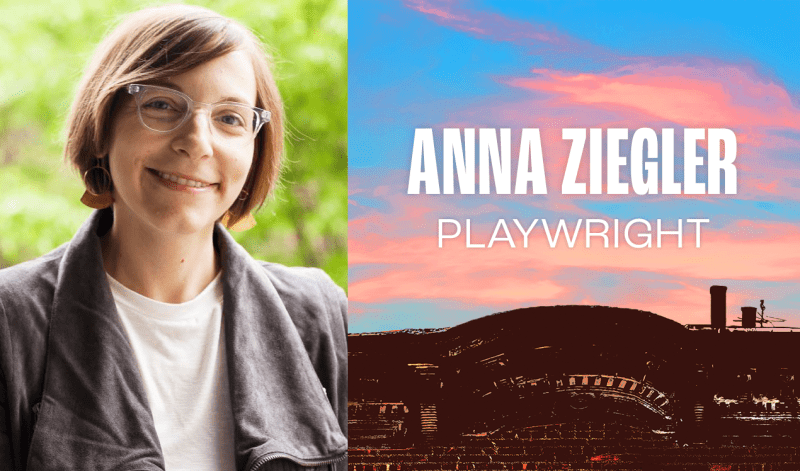

Teaching Artist Leah Reddy spoke with playwright Anna Ziegler about The Wanderers.

Leah Reddy: What is your theatre origin story?

Anna Ziegler: I’d say there isn’t a single story. I grew up in New York City, so I went to see a lot of theatre (mostly musicals) as a kid, and I loved those experiences. I went to an artsy progressive school in Brooklyn that offered playwriting in high school and got up the nerve to take that class in 12th grade (only to find myself at the high school playwriting festival at the end of the year clutching the arm of my chair, filled with the same terror I experience to this day watching my own work). But it probably wasn’t until the summer after college, when Arthur Kopit (whose class I took as an undergrad) invited me to join The Lark’s inaugural Playwrights Workshop — where I wrote my first full-length play in a sort of fever (never to be repeated) — that I started to get hooked on the idea of making my life in the theatre.

LR: Were there any teachers or educational experiences that inspired or helped you? If so, how?

AZ: Growing up and in high school, my teachers Marty Skoble, Beth Bosworth, and Elise Meslow made me feel like a writer — like I was already a writer. My school (Saint Ann’s School, in Brooklyn) churned out writers the way Wharton churns out investment bankers, in part because many of the teachers there are writers themselves and make that life seem real, and possible. I mostly wrote poetry at Saint Ann’s and in college, but as an undergrad I was lucky enough to take two playwriting seminars too. These were taught by Donald Margulies and Arthur Kopit, both of whom admitted me on the basis of poetry I’d written, as opposed to plays. I’m grateful to them for seeing something in me I didn’t yet see myself. Especially Arthur — who told me I was a playwright, and then shepherded me into The Lark and then to NYU for graduate school. I’d always tell Arthur that I both thanked him and cursed him for leading me into a life that was not without its challenges. He died last year, and I wish I could let him know (I hope he knew) that I’m much more grateful than anything else. If not for him, I’d have gone out to San Francisco in 2002 to work at this literary journal, The Threepenny Review (I’d been offered a job there at the same time as I was offered a spot at NYU) and while a life in books and publishing might well have been satisfying, I feel pretty confident that I ended up in the better lane for me.

LR: What inspired you to write The Wanderers? What drew you to explore the Hasidic community, and the questions this play raises about Jewish community and identity?

AZ: I’d always wanted to write about an arranged marriage. I’m fascinated by the idea of them — particularly by what it would feel like to pledge oneself to someone you barely know, and what those first days and nights might contain — I mean, how could that first week not represent a microcosm of the human condition?? How could any emotion be left out? And because I’m Jewish it felt natural to write about an arranged marriage inside of that community and to write about one in that community meant writing about an Ultra-Orthodox community.

In the summer of 2016, when I was working on my arranged marriage play, initially set in Monsey, NY, I was also working on another play about marriage — this one the marriage of a secular Jewish couple in New York City. This couple was threatened by an intrusion from the outside world, the presence of which unearthed some of the couple’s internal struggles, whereas the Hasidic couple in my other play was threatened by internal struggles — struggles that existed inside of these people and their community — that kept the outside world at bay. By the end of the summer I realized I was actually writing one play — after all, both couples were straining against the perceived boundaries of their lives, but in different ways — and I spent the next several months stitching the stories together (moving them both to Williamsburg, Brooklyn, for one thing).

LR: Are there any insights into your writing process you would share with young or emerging playwrights?

AZ: Well, I have many more play fragments that I couldn’t manage to stitch together into a single play than instances where I could, so I don’t know that I’d advise spending too much time on that particular exercise. In general, I’d say that my process has been…not to force the writing. I know that many writers feel very differently, but I tend to find that when I force myself to write, or feel uninspired, the work that emerges is also generally uninspired. So if my writing “process” is any model, it’s largely about trying to be forgiving of oneself on those days (or weeks, or months) when the writing doesn’t come.

LR: The Wanderers includes scenes that take place online, in email exchanges. How do you approach writing about online life for the stage?

AZ: I approach it mostly by not thinking about these scenes as being online. I wrote the dialogues between Abe and Julia as though these two characters were in the same room; I think we’ve reached a place in our online discourse where we can be as frank and natural as we are in in-person interactions, or, if anything, franker, which is helpful in a play where you want people to slip into revealing more than they intend to or be bolder versions of themselves.

LR: What do you hope audiences take away from this play?

AZ: I hope, to steal a line from the play, that it makes people think about putting aside a sort of galvanizing restlessness that leaves us always empty. To endeavor to enjoy our lives for what they are as opposed to what we’d wish them to be — a nearly impossible task (for me, at least) but worth a shot anyway.

LR: Is there anything I haven’t asked you that you’d like to talk about?

AZ: I’d just like to thank the amazing Roundabout for sticking with and standing by this play all these years. The theater first committed to the play in 2018; it would have been produced here two years ago if not for COVID-19, and of course the world has changed in that time, in ways large and small, and one never knows how a piece of art will be perceived in a different moment. For one thing, TV shows and movies about Hasidic life have suddenly become de rigueur, which could either make this play feel more relevant or annoyingly trendy (though I’d humbly point out that I wrote the early drafts of this play in 2016 before Unorthodox, Shtisel, and My Unorthodox Life were in the American consciousness…) Either way, I’m grateful to Todd and Jill and Anna and Nicole and everyone at Roundabout who continued to champion the play. Todd promised me that he would eventually produce it but, being a worrier, I wasn’t sure. I’m so thankful we’ve finally reached this moment and, again, to steal from the play, I feel just how fortunate I am.