Toni Stone:

On Tour With the Clowns

Posted on: August 5, 2019

For Toni Stone, her teammates on the Indianapolis Clowns, and all other black baseball players in the early- and mid-1900s, the only way to professionally play the sport they loved was to endure the grueling schedules and pervasive discrimination of a career in the Negro Leagues. What was life on tour like for Toni Stone and her fellow ballplayers?

A Relentless Season

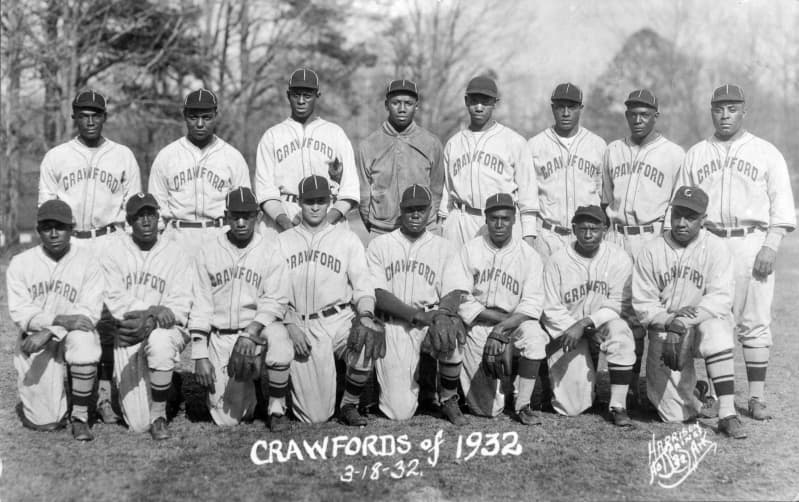

While everyday life for Negro Leaguers depended greatly on the financial situation of their particular team owner, all players’ daily schedules were nonstop. Each year, pre-season barnstorming games would begin for Negro League teams as early as February, with their regular season starting in April and ending in September. Negro League teams would, if possible, play a ballgame every day — sometimes even three or four — in order to keep the teams themselves in business and make the players enough money to live on. In between games, teams would travel up to hundreds of miles from town to town, sometimes overnight, on buses or in touring cars that could be uncomfortable and prone to breakdowns.

The Negro Leagues and Jim Crow

Negro League teams generally sought to forge connections with the local communities that they visited. Some towns welcomed players, but in many others, Negro League teams would have to contend with the discrimination of Jim Crow laws — statutes in existence from the end of the Civil War to the end of the Civil Rights Era that instituted racial segregation on the state and local levels and denied rights to black citizens.

Negro League teams like the Clowns were often prohibited from white-owned hotels in the towns and cities where they spent the night. For lodging, then, players would stay at black-owned hotels, or with black homeowners — generally Negro League fans — who opened their doors to them. Finding a meal could be a challenge, as white restaurants frequently wouldn’t serve Negro League teams or required players to take their food at the back door.

Clowning and Minstrelsy: Performance on the Field

A Clowns game featured much more than standard baseball. In addition to playing a regular game, the team would incorporate bursts of “clowning” — that is, a performance of a sort of “imaginary baseball” using exaggerated physicality, comedic timing, and feigned foolishness. While these tricks were impressive, team owner Syd Pollock’s influence often caused them to verge on minstrelsy — a kind of performance founded in false and negative racial stereotypes, designed to make others laugh at the expense of marginalized people.

Minstrel acts first gained widespread popularity in 1830, when white actor Thomas Rice performed in New York as the character Jim Crow (after whom Jim Crow laws were later named), an offensive caricature of a disabled black stable groom. Darkening his face with makeup, Rice sang and spoke with an exaggerated accent and slowness, reinforcing negative stereotypes about enslaved black people. Rice and his peers helped make minstrel acts the most popular form of entertainment in the United States in the years preceding the Civil War.

The popularity of minstrelsy waned in the early 1900s, but television, film, and radio programs featured white actors portraying black people well into the 20th century. And when black actors were cast, their characters also contained offensive stereotypes. But for countless black actors, performing in these roles was the only way to gain access to Hollywood.

As the Indianapolis Clowns’ experience attests, some white owners of 1930s and ‘40s-era Negro League teams designed those teams with minstrelsy in mind. Owners assigned teams derogatory names like the Coconut Grove Black Spiders and the Florida Colored Hoboes. The Indianapolis Clowns themselves started as the Zulu Cannibal Giants (later the Ethiopian Clowns), who were made to wear costumes of stark white face paint, clown wigs, and grass skirts. When Syd Pollock bought the team in 1937, he renamed them the Indianapolis Clowns.

Though Pollock replaced the grass skirts with ruffled collars, the white greasepaint remained, and Pollock capitalized on the “novelty” of his players’ blackness and talents. He aggressively advertised their slapstick routines, and when black sportswriters critiqued his team management, he’d rent space in the papers to write angry op-eds defending his choices.

By 1943, however, when the Clowns were officially incorporated into the Negro American League, much of the belittling costuming and overt minstrelsy ended, in accordance with League regulation. And while physical comedy remained a hallmark of the Clowns’ reputation, the team began to play by-the-book baseball.

On the Road and on the Field as the “Gal Guardian”

As the only woman on her team — and in the Negro Leagues overall — Toni Stone faced added targeting every day. It was in the advertising for the Clowns where Stone felt most “capitalized on.” Syd Pollock scouted Stone as an answer to lagging ticket sales, marketing her gender over her athleticism when he dubbed her “the Gal Guardian of Second Base” in 1953.

A first clash between Pollock and Stone came with the question of her uniform: when told she’d be wearing a skirt-and-shorts combination, Stone refused: “I wasn’t going to wear no shorts.” As some male sportswriters responded negatively to a woman on the field, Pollock relied on promotional pieces to soften Stone’s image, often enlisting black-owned publications to promote her as demure and unthreatening.

A spread in Ebony magazine showed her applying makeup in a mirror. One caption read: “Stone is an attractive young lady who could be somebody’s secretary.” Others commented on her size, the shape of her figure, and whether or not she was good “wife material.” Stone resented these sexualizing comments, feeling displayed “like a goldfish” and wanting to represent herself on her own terms.

Through all the unique challenges of a life in the Negro Leagues, Toni Stone and her fellow ballplayers drew strength from each other and from their love of the game to return to the field again and again. In remaining dedicated to their game, they paved the way for the racial integration of the Major Leagues in the mid-20th century.

Toni Stone is now running through August 11th at the Laura Pels Theatre.