Jump to:

The setting of a play is never random. It is a deliberate choice that creates or contributes to the conflict and mood by virtue of its inherent qualities or an audience's preconceived notions—even if it is not the playwright’s first thought. In a recent Upstage interview, playwright York Walker describes how the inspiration for Covenant came to him. First, there was an image of a girl in a blue dress that kept coming to mind. Once he had the image of the girl, he began to see the world she inhabited, and it happened to look like the town from The Color Purple. "In my head,” he said, “that's where this play takes place.” In the same interview, Walker goes on to say:

I am fascinated with period pieces, especially period pieces with Black people. I'm so curious as to how Black people lived their lives in the past and got through all the terrible things that were going on, and especially Black queer people. How do they navigate the world in different time periods?

Walker may not have specifically chosen rural Georgia in 1936, but by finding himself drawn to the setting of The Color Purple, an incredibly specific world to navigate clicked into place—a world that pressured Black women into following strict rules governing faith, sexuality, and gender that often had devastating consequences whether they were adhered to or not.

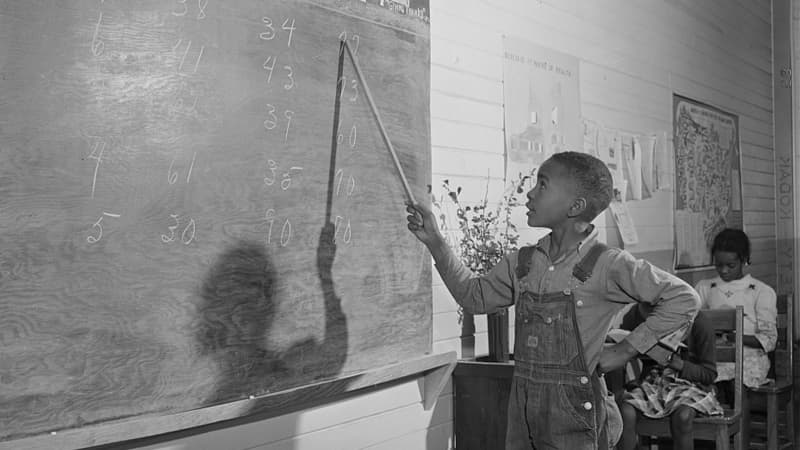

Boyd Jones doing his arithmetic lesson at the blackboard in the Alexander Community School in Greene County, Georgia.

Photo by Jack Delano/Library of Congress.

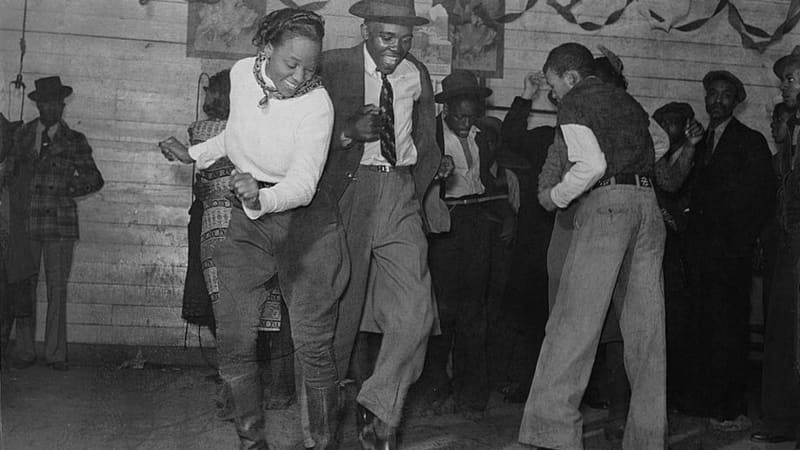

A couple dances the jitterbug in a juke joint outside Clarksdale, Mississippi in 1939.

Photo by Marion Post Wolcott/Library of Congress.In 1936 the United States was a nation in distress navigating the impact of the Great Depression, which caused internal displacement and migration. In the previous decade, many Black Americans moved from the South to the North in the first wave of what came to be known as the Great Migration. Between 1910 and 1930, larger northern cities like New York and Chicago saw their Black populations grow by about 40 percent. Additionally, the number of Black industrial workers doubled. While those who moved north had their own obstacles, those who remained in the rural South continued to struggle against specific regional disparities. By 1930, nearly 90 percent of urban homes had electricity while only ten percent of farms did. This is just one example of an advancement in the standard of living that didn’t reach struggling farmers. Ironically, advancements in farm technology led to over production that ultimately caused the price of crops to plummet. Additionally, an infestation of boll weevils—beetles that feed on cotton buds and flowers—significantly impeded the production of the South’s most important cash crop, cotton. This caused a major financial disruption that would only be exacerbated in the 1930s with the onset of the Great Depression. In Georgia, New Deal initiatives to aid impoverished farm workers were slowed by Governor Eugene Talmadge whose resistance was fueled by bigotry and fear that these projects would serve as an equalizer between the races. Despite his efforts, several projects were initiated. One such project was the Rural Electrification Act, signed May 20, 1936. The REA not only brought electricity to the area, but also created thousands of jobs. By 1942, half of US farms had power.

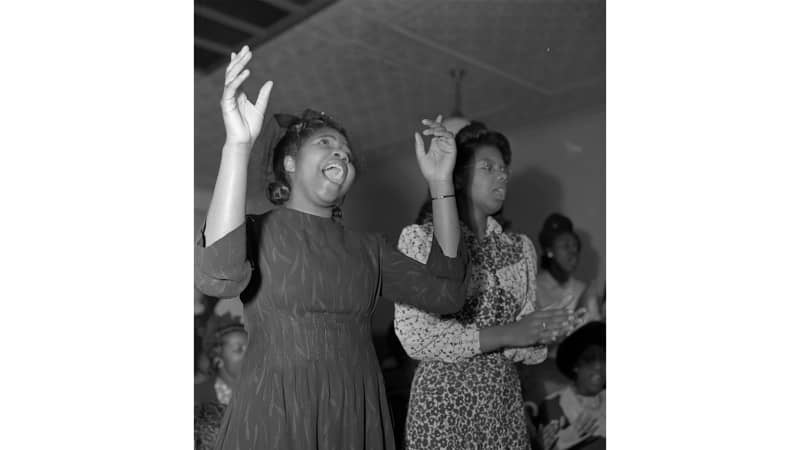

Members of the congregation of the Church of God in Christ in Washington, DC, in 1942.

Photo by Gordan Parks/Library of Congress.While there is little by way of specifics about the town in Walker’s play, it is evident that church and religion are the backbone of the community’s norms and expectations. Formalized Christianity for Black Americans was an opportunity to find comfort in community, create social safety nets that didn’t exist for them otherwise, mobilize a civil rights movement, and nourish a flourishing culture. Historian Henry Louis Gates notes:

We do the church a great disservice if we fail to recognize that it was the first formalized site within African American culture perhaps not exclusively for the fashioning of the Black aesthetic, but certainly for its performance, service to service, week by week, Sunday to Sunday.

It is important to note that while the term Black church is a useful umbrella term, the many denominations and congregations are not a monolith. Between 1896 and 1916 six major denominations were founded: African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, African Methodist Episcopal Zion (AME Zion) Church, Christian Methodist Episcopal (CME) Church, National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc., Church of God in Christ (COGIC), and the National Baptist Convention of America International, Inc. The term "the black church" evolved from the phrase "the Negro church," which primarily served as an academic term by social scientists such as W.E.B DuBois who sought to edify Black culture by using an academic lens to name its existence. Formalized study was a means by which to elevate the Black experience to the same plane as predominantly white fields. In his 1903 report on the Eighth Conference for the Study of the Negro Problems, held at Atlanta University, DuBois notes:

The Negro Church is the only social institution of the Negroes which started in the African forest and survived slavery; under the leadership of priest or medicine man, afterward of the Christian pastor, the Church preserved in itself the remnants of African tribal life and became after emancipation the center of Negro social life. So that today the Negro population of the United States is virtually divided into church congregations which are the real units of race life.

Over 100 years later, Henry Louis Gates echos the observation DuBois made and articulates the reason for the continued use of such an all-encompassing term, writing:

Collectively, these churches make up the oldest institution created and controlled by African Americans, and they are more than simply places of worship. In the centuries since its birth in the time of slavery, the Black Church has stood as the foundation of Black religious, political, economic, and social life.

The establishment of a Black church in the United States traces its roots back to slavery. Prior to enslavement, some Africans were Christian but many more were followers of traditional religions specific to regions in West Africa. Influence from Christian missionaries began to affect a shift in religious practices of enslaved people, something many slaveowners opposed. They feared that a shared religion would result in a belief that they were each other’s equals. Enslaved Black Christians had to deal with restrictions by masters who forbade them from attending church or prayer meetings as well as sermons from white clergy who preached obedience to their slaveholders. Services were held in secret, often in cabins, ravines, thickets, or any other place that offered cover for their own distinct style of prayer and song. Perhaps emboldened by faith, worshippers did not remain shrouded for long. The founding of the earliest Black Christian congregations was roughly contemporaneous with the Declaration Independence (1776). Significantly, Black churches were the first institutions built by Black people and run independent of white society in the United States. Autonomy was in fact necessary as they were confronted by white Christians who still would not allow them into the fold. For example, Richard Allen found faith while still enslaved but even after purchasing his freedom was ejected from a church when he was found praying in a segregated space. His expulsion led, in part, to his founding of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1816. This model of carving out specific spaces and organizations for themselves would continuously be employed by Black Americans across all sectors of life – religious, academic, and entertainment.

As previously mentioned, the Great Migration was marked by a huge movement of people. This led to increased dissemination of Black denominations as well as the proliferation of new congregations. They provided a source of community and familiarity to folks adjusting to urban life, led deftly by confident ministers. Meanwhile, those who remained in the rural south had to cope with the dwindling population and economic disparities. Ministers were frequently uneducated, and congregations were held together by lay members: “deacons, ushers, choirs, song leaders, Sunday school teachers and "mothers" of the congregation.”

Fourth of July in St. Helena, South Carolina, 1939.

Photo by Marion Post Wolcott/Library of Congress.In the era of Covenant, many Black Americans saw Christianity as a possible route to acceptance by white society. As such it was crucial to strictly adhere to its teachings in a way that lifted the perceived virtue of their entire community. “Mothers” of the congregation were informally tasked with policing the behavior of their community by uplifting moral choices and admonishing perceived deficiencies of character from promiscuity to idleness. This campaign is a major tenet of “politics of respectability” as identified and described by Professor Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham as the promotion of temperance, cleanliness of person and property, thrift, polite manners, and sexual purity. The goal was to reform individual behaviors as a strategy to shift racist preconceptions and thus achieve equal consideration under the law. While adherence to respectability enabled Black women to counter racist ideas and structures held by their white counterparts, it also created opportunities to viciously condemn what they perceived to be negative practices and attitudes among their own people. Two areas of focused disdain were music and sexuality.

Gospel music is closely associated with the culture of the Black church yet its contemporary, the blues, was often condemned as “devil’s music.” Around the turn of the century, many congregations still worshipped with no instruments and sang acapella as was part of many folk traditions. These hymns and spirituals were considered sacred music, but to evolve those into something secular was sinful. In Covenant, Mama chastises Johnny: “You in a house of God with an instrument of the enemy. Unless they started playin’ the guitar during service on Sunday mornin’.” Mama gives voice to a prevailing notion of the time—that music could be the root of immoral behavior and personal ruin. The threat of the blues was imbued by its performers who borrow sounds from their churches but stripped away faith. Music historian Paul Oliver explains:

In its bare realism the blues is somewhat bereft of spiritual values. [Black Americans] often had to decide whether to accept with meekness the cross they had to bear in this world and to join the church with the promise of “Eternal Peace in the Promised Land” or whether to attempt to meet the present world on its own terms, come what may. The blues singer chose the latter course.

Sacred music and the blues were two sides of the same coin. Each was the expression of a person with doubts and questions and longings, but one was calling onto the Lord for strength while the other was sure they were on their own. The solace and comfort found in the blues competed with that which the Black church offered, threatening its place of power in the politics of respectability. In some lights, one might see the juke joints as a kind of secular church: a meeting place where folks could express their innermost thoughts and desires and be in community with other seekers. Speaking on the danger of secular music and juke joints, one Baptist leader stated that "improper dancing will completely demoralize the womanhood of today.” Note in this reprimand that the concern surrounding deteriorating morality was aimed squarely at women.

Men were just as vulnerable to condemnation from “mothers” of the church, but young women were assumed to shoulder the responsibility of maintaining and promoting respectable, chaste behavior. There is now a plethora of work that supports the pattern of hyper-sexualization and demonization of Black women and its role as a tentpole in white supremacy. This was another stereotype that the politics of respectability sought to debunk. In 1941, Charles Johnson published Growing Up in the Black Belt: Negro Youth in the Rural South, a study on the attitudes and behaviors of southern young people. One participant voiced her great fear of not “being saved” and being sent to hell instead of heaven. From her view, the greatest sin was a pre-marital pregnancy followed, in order, by drinking, killing, then stealing. Girls were warned against the outcome of sex (having a baby out of wedlock) to avoid discussion of sex itself, a topic too taboo to broach with young people. Many families were mindful to create environments in which it would be nearly impossible for premarital sex to occur. It was standard practice of parents to implement age restrictions around dating and when a daughter came of age to enforce supervision and curfews. This can be seen in Mama’s behavior with Avery throughout Covenant. Even when Avery and Johnny are in church alone, a place associated with sanctity and good behavior, Mama is suspicious—and perhaps rightfully so. In Susan Cahn’s book, Sexual Reckonings, she notes that sexual encounters took place most often in areas and during times identified with safety or moral health: the home, the fields, the woods, and during the day, after church or while school was in session. This illustrates a distinct dissonance between expectations and reality surrounding sexual behavior. The vilification of a pregnancy outside of marriage did little to affect the opinion or actions of young people. In the same study mentioned above, a 15-year-old girl recounted having a mother who deterred her from dating and yet she was still sexually active. She said, “I tell the boys not to make me pregnant. . . I don't see nothing wrong 'bout it, so long as they don't mess me up." This was the consensus of the majority of her peers: sex was fine if you weren’t caught and didn’t get pregnant. Other young people made mention of non-consensual or incestuous sexual encounters which were seen as outside the informally established norm of premarital sex and widely understood to be wrong. However, these violent and manipulative transgressions were just as much avoided as a topic in conversation between peers as the topic of consensual sex was between parents and children. A culture based on the politics of respectability couldn’t stem the natural human impulse towards sex, but it did indirectly cultivate environments in which physical and psychological harm could thrive in silence.

In a 1989 essay, historian Darlene Clark Hine theorized that Black women were driven to create a culture of dissemblance, meaning “the behavior and attitudes of Black women...that shielded the truth of their inner lives and selves.” She asserts this grew out of the prevalence of, as well as constant threat of, sexual assault and a desire to protect one's inner self if not her physical self. In partnership with respectability, this practice “enabled the creation of positive alternative images of their sexual selves and facilitated Black women's mental and physical survival in a hostile world.” Hine named this phenomenon so that there would be a framework for excavating and analyzing the contributions and narratives from Black women in American history. Today, we can see fierce refusals to cow to dissemblance, most visibly in the music industry in albums like Beyonce’s Lemonade and Janelle Monae’s Dirty Computer which loudly proclaim and explore Black women’s desires.

In Covenant, much goes unnamed. Most of what the audience learns about the women’s inner lives comes from soliloquies delivered as interludes between scenes. Even at that, the characters speak in the third person, putting distance between themselves and their truths. There is no pastor, nor is there a scene where we see what services look like for this congregation. Still, the power of the church is keenly felt even in the women’s most private moments.

Published on October 19, 2023.

References

|

Cahn, Susan K. Sexual Reckonings: Southern Girls in a Troubling Age. Harvard University Press, 5 March 2012. DuBois, W.E.B., editor. Eighth Conference for the Study of the Negro Problems. 26 May 1903. Atlanta, Georgia. 1903. Evans, Curtis J. The Burden of Black Religion. United Kingdom, Oxford University Press, 2008. Gates, Henry Louis. “How the Black Church Saved Black America.” The Harvard Gazette. 9 March 2021. Gates, Henry Louis. “To Understand America, You Need to Understand the Black Church.” Time.com, 17 Feb. 2021. “Great Migration: The African-American Exodus North.” Fresh Air, NPR, 13 Sept. 2020. Transcript. Higginbotham, Evelyn Brooks. Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880-1920. Harvard University Press, 15 March 1994. Johnson, Charles Spurgeon. Growing Up in the Black Belt: Negro Youth in the Rural South. Schocken Books, 1941. Internet Archive. Mellowes, Marilyn. “The Black Church.” God in America, PBS.org, 2010. Oliver, Paul. Blues Fell this Morning: The Meaning of the Blues. United Kingdom, Cassell, 1960. Pew Research Center. “Chapter 10: A brief overview of Black religious history in the U.S.” Faith Among Black Americans. 16 Feb. 2021. Raboteau, Albert. Slave Religion: The ‘Invisible Institution’ in the Antebellum South. Oxford University Press, 7 Oct. 2004. Shipley, Jonathan. “A Light Went On: New Deal Rural Electrification Act.” LivingNewDeal.org, 5 Dec. 2020. |