In the dedication of Doubt: A Parable John Patrick Shanley writes:

This play is dedicated to the many orders of the Catholic nuns who have devoted their lives to serving others in hospitals, schools and retirement homes. Though they have been much maligned and ridiculed, who among us has been so generous?

In writing Sister James and Sister Aloysius, Shanley created three-dimensional characters out of what is often a trope: the Catholic nun. This article delves into the history of nuns, their role in the American church in 1964, and issues they face today.

An illustration of 12th century nun Hildegard of Bingen receiving a vision from God. Bingen created this illustration as part of her book Scivias (completed in 1175), which tells the story of 26 of her visions.

Women in the Catholic faith have never been permitted to be priests, but women who wished or felt called to devote themselves to the church and a life of doing good works have the option to join a Catholic religious order in which their lives would be devoted to service and prayer. These women are called nuns or sisters.

Nuns began as early as the fourth century, when women (and men, known as monks or brothers) began to remove themselves from society to follow lives of religious contemplation in monasteries or cloisters. This was mostly something women of upper classes could afford to do.

Women in these communities began to wear special clothing, or habits, that set them apart from other women; the type of habit told what congregation one belonged to. In 1215, a law was made within the church saying that women of religious orders not wearing habits could be excommunicated, so habits became the rule. It is around this time that the term “nun” came into use.

In 1298, Pope Boniface VIII issued a proclamation that nuns must live away from society (especially away from the company of men), devoting themselves to prayer – they had no place in the day-to-day life of the church. This hampered what a nun could do beyond the cloister walls.

In the 1600s two French Catholics – Father Vincent de Paul and Louise de Marillac, a devout widow – realized the wasted resource of cloistered servants of God, and recruited women interested in serving the poor. These women were called the Daughters of Charity. Their numbers grew, and soon they were serving all over France in hospitals, schools, and poorhouses. They were referred to as secular sisters as opposed to nuns. Now, the terms sister and nun are interchangeable.

Today, nuns teach in Catholic schools or universities, work in hospitals or nursing homes, run orphanages, assist immigrants to this country in myriad ways, and serve in many other social justice-related causes.

Becoming a Nun

A woman goes through a process, called formation, to become a nun. First there is a trial period in which she lives in a convent as a postulant. If the nuns of the convent think her a good fit for their order, she takes the next step as a novice. As a novice, she will change her name, and she will take a temporary vow of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Once she is deemed ready she takes her permanent vows and is considered formed. This final process typically takes several years.

During this trial time of years, she will be put to the test. It is important to be obedient to the Mother Superior, who has authority over the other nuns in her order, and to be humble. Being a nun means turning one’s back on the day-to-day life of marriage and family. This life allows one, in the nun’s experience, to be closer to God.

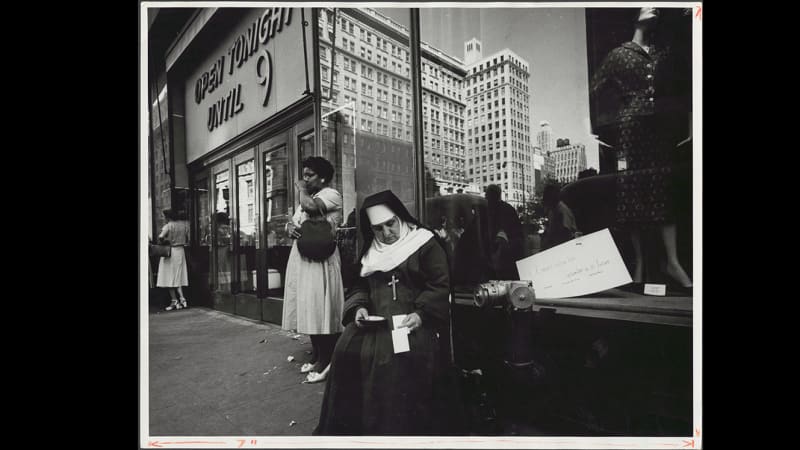

A nun sits outside a store in New York in 1958.

Photo by Angelo Rizzuto, Library of Congress.In the early 1960s, when Shanley was young, nuns were a visible presence in many neighborhoods, serving as teachers, nurses, and in other service roles. They were the face of the church, even as they lacked power in the church’s hierarchy.

This was evident during Vatican II, a years-long process to rewrite the constitution of the Catholic Church to make it more inclusive and relevant to the modern world. It wasn’t until the last two meetings that a small number of nuns – 23, compared to almost 3,000 male participants and observers – were invited to observe the proceedings.

Six nuns were eventually invited to sit on a commission that created the Pastoral Constitution of the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes). These six women joined thirty bishops, forty-nine theological experts, and ten laymen (non-ordained members of the church). With full voting rights, they helped draft one of the most important documents of the Council, one that emphasized human rights and social justice. One of its passages reads: “With respect to the fundamental rights of the person, every type of discrimination, whether social or cultural, whether based on sex, race, color, social condition, language or religion, is to be overcome and eradicated as contrary to God’s intent.”

One of the other major shifts that came from Vatican II was that Catholicism was now understood to be one of many valid religions, not the “one true church,” and clergy were no longer considered above the laity. By making the texts and the process of the mass more accessible to all, the sacrament of baptism made all Catholics “people of God.” Holiness was now considered the responsibility of every Catholic. This put nuns in a precarious position. Not really being ordained members of the clergy or hierarchy, their devotion to the church, their “holiness,” was what set them apart from the masses, what made them special. Some sisters welcomed this leveling of the playing field, others were left adrift by this loss of elevated status.

The reasons are as varied as nuns themselves are, but women began to leave the sisterhood in droves after Vatican II, and the enrollment of new nuns has never rebounded. The above mentioned “loss of status” may be part of the shift. But, in general, 1960s society was more questioning; a nun’s vows to “poverty, chastity, and obedience” were less attractive to young women being drawn into a growing feminist movement. (Although, one could argue nuns were at the forefront of feminism where employment was concerned). Previously, joining a religious order had given a woman an elevated status and opportunities for a higher education. By the late 1960s, women had more options for upward mobility. They could also choose to have a family while seeking holiness as a layperson.

The Sisterhood Today

The Catholic Church thrives in the United States today in terms of numbers, with 66.5 million Catholics reported connected directly with a parish, and 73.5 million self-identifying as Catholic in 2022, but the reputation of the church has been rocked in recent decades due to the unmasking of sexual abuse and systems of coverups.

Meanwhile, the number of nuns of religious orders are both decreasing in number – 36,321 in 2021 compared to 74,162 in 2001, down from 179,954 in 1965 – and aging, with 81% over the age of 70.

In the past it was the younger sisters entering the orders whose small stipends from teaching, health care, and other service work supported the day-to-day operations of their order and the care of retired sisters. With very few young women entering the orders in recent years, many retired nuns face uncertainty. In fact, since nuns drew “stipends,” not salaries, it was not until 1972 that federal laws changed to allow members of religious orders to draw Social Security.

Retired nuns play bingo in February 1984.

Photo by Bernard Gotfryd, Library of Congress.These facts were brought to light in 1986 when the Wall Street Journal published a front-page article by John Fialka: “Sisters in Need: U.S. Nuns Face Crisis as More Grow Older with Meager Benefits.” Until then, most people believed the church financially supported sisters and non-ordained men (brothers) like they do priests, not understanding their unique relationship to the church. Fialka, who was educated by nuns, was moved by the outpouring of concern after the publication of his article and went on to help found SOAR! (Support Our Aging Religious), a fundraising organization for the cause of supporting elderly sisters and brothers of religious organizations.

Young nuns on the boardwalk at Coney Island.

Though many sisters are in their golden years, some women continue to be drawn to both the structure of religious life and nuns’ commitment to social justice and public service. In January of 2024, 250 nuns under the age of 65 from around the world gathered to discuss the future of religious life for sisters and build community. Though their numbers in the US are down, the sisters' work continues: assisting migrants and refugees, teaching at all levels, working with survivors of human trafficking, advocating for causes, caring for the sick, and supporting those in poverty.

References:

|

Note: Members of the New York Public Library can access JSTOR and many other research databases through the library’s Articles & Databases page. Briggs, Kenneth. Double Crossed: Uncovering the Catholic Church's Betrayal of American Nuns. Doubleday, 18 Dec. 2007. Bunson, Matthew. Our Sunday Visitor’s Encyclopedia of Catholic History. Our Sunday Visitor Publishing Division, 1995. McGuinness, Margaret M. Called to Serve: A History of Nuns in America. New York, New York University Press, 2015. “Ministries and Roles within the Liturgical Assembly at Mass” United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Stockman, Dan. “Conference to Help Younger Religious Sisters Build Community Called ‘Transformational.’” Northwest Catholic, 15 Feb. 2024. O’Toole, James M. The Faithful. Harvard University Press, 30 Mar. 2010. |