Jump to:

If we don’t breathe, we die. If we don’t drink water, we die. And if we don’t eat food – you guessed it – we die. Human beings have always been consumers of necessary resources. It's a fact of life: we consume to survive. But at some point, we also became economic consumers, people who buy and own things. Like Sam, the main character in I Need That, who fills his home with all different kinds of stuff. Consumerism is woven into US history and culture, but is that a good thing? As you read about the history of consumerism in the US, consider your own relationship and history with possessions and, perhaps, consider: how did you end up with all this stuff?

A Very Short Summary of the Origins of Consumerism

Before the Industrial Revolution – the shift from an economy dominated by small farms and hand-made goods to one built around machine manufacturing and large industries – all but the wealthiest Americans owned the necessities of life and little else. They might own several outfits worth of clothes, cookware, tools, furniture, and books, almost all of which were handmade and expensive.

Three shifts made consumer goods more affordable to the masses. The first: slavery, which made raw materials like cotton and sugar cheaper, leading to a boom in consumer goods in the 19th century. The second: the shift toward machine manufacturing – often done by low-paid immigrants or children – put new products within reach of ordinary Americans. Finally, the shift toward big businesses, driven by the need to make a profit for their shareholders, led to an increase in advertising and positioning new, cheap goods as something consumers just had to have.

A teacher demonstrates how the US rationing program works to a group of students. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information Black-and-White Negatives.

World War Two (WWII) was a time of increased production in the United States, in which the entire economy was organized around supplying the Armed Forces and US Allies. Under the direction of the War Production Board, the country’s war-related production went from two percent of the US gross national production to 40% by 1943, creating goods and armaments valuing a total of $185 billion from 1942 to 1945. This industrial mobilization also significantly boosted the country’s production infrastructure and capability.

It was also a time of great frugality. So many goods and raw materials were needed to support the war effort that the Office of Price Administration ran a rationing system which placed limits on both price and consumption of a variety of common goods like shoes, gasoline, tires, butter, and cigarettes. There was even the Consumer’s Victory Pledge, in which people were encouraged to abide by three promises: “I will buy carefully. I will take good care of the things I have. I will waste nothing.”

These wartime trends, increased production and decreased consumption, would ultimately set the stage for what came next.

Children in the 1950s look at a Christmas display of toys.

The period after WWII would eventually be referred to as “The Consumer Era” and came about due to several factors. The end of wartime rationing meant that there was a release of a pent-up demand for goods – people were ready to go buy some stuff. And they had the money for it. The American middle class was expanding. Over four million veterans returned home, and thanks to the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 (commonly known as the GI Bill), they were given access to the resources they needed to successfully re-enter the domestic economy. Money for higher education meant veterans could get better paying jobs. Low-interest rate mortgages meant veterans had empty houses to fill with home goods. They also had to buy things for their spouses and children. After WWII there was a huge boom in both marriages and fertility rates – this is the origin of the term “baby boomer.” One of eight children in his family, Sam is a baby boomer who grew up in this era, and this experience informs his worldview throughout I Need That.

It’s worth noting that not all this prosperity and abundance was available to everyone. Black soldiers were overwhelmingly unable to access the benefits of the GI Bill due to the segregationist and discriminatory practices of the time. Financial institutions refused to approve their mortgages, and universities often slow rolled or outright denied them admission. This led to a further widening of the racial wealth gap, which persists to this day.

At the same time, the price of goods was falling, making the consumer lifestyle much more accessible. An emerging global supply chain, dependent on cheap and exploited labor abroad, provided cheap products. New technologies also changed manufacturing – plastic, invented in 1933 and further developed as insulation for different military applications in WWII, was used to create everyday products like garbage pails, Tupperware containers, and even hula hoops.

This era was also the beginning of consumer credit, or credit cards. The Diner’s Club Card, launched in 1950, was first only used in New York restaurants. While the initial terms were not great by modern standards (users had to pay off the full balance at the end of each month), it was nevertheless popular. By 1952, the number of cardholders had more than doubled to 42,000 and covered more services like hotels and flower shops. By 1953, it had spread across the country and begun to be used internationally.

So, what did people buy at this time? In many ways, the same kinds of things we buy today. Items to fill their homes, keep up with their neighbors, and make their lives more convenient. Garbage disposals, cars, dishwashers, toasters, vacuum cleaners, and perhaps most importantly, televisions. And with TVs came TV commercials, marketing in technicolor selling people a post-war future of optimism embodied by things to buy.

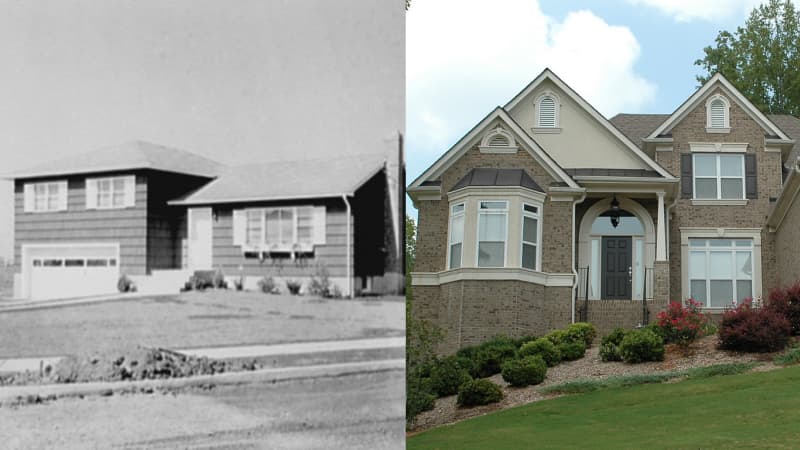

Left: a model suburban home in 1954. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Gottscho-Schleisner Collection [LC-G613-T-65120]. Right: A new suburban home, 2017.

Today, we’ve got even more things than the post-war folks. Online shopping fueled by social media ads has made shopping that much easier, supplanting brick-and-mortar businesses and TV advertising. E-commerce businesses like Amazon saw record profits during the pandemic. Overseas manufacturing has also expanded, leading to even cheaper goods. “Fast fashion” companies that sell mass-produced, cheap, trendy clothing rely on the exploitation of overseas workers to make a profit. Replacing the optimism of the consumer era, we often purchase products as a response to anxiety – think fidget spinners, weighted blankets, sun lamps, and adult coloring books.

With more stuff comes more space to store it. In 1949, the average single-family home was 909 square feet, and by 2021 that number had more than doubled to 2,480 square feet. But it may not be to our benefit. A recent UCLA study found that people experience more stress based on the amount of clutter in their homes. In fact, there’s so much of that clutter, we need space outside the home. The personal storage industry was valued at $48 billion worldwide as of 2020, and almost 10% of Americans rent a storage unit. This adds up to a global footprint of 2.3 billion square feet. There are so many of these units that they are often abandoned and then auctioned off, creating a multi-million-dollar secondary industry.

What Now?

What’s next for consumerism? There’s some evidence that we may be moving away from this lifestyle. Minimalists strive to own as few things as possible, believing that “less is more.” The tiny-house movement encourages people to build and live in homes under 400 square feet. Ethical consumerism tries to reshape the consumer impulse, by advocating that people purchase products that are ethically sourced, made, and distributed. A new profession, organizing consultation, has sprouted up to help people organize the things they love and need, and get rid of everything else.

In I Need That, Sam struggles to make this distinction between which objects matter and which ones don’t – he loves and needs it all. Each thing seems to contain a precious memory, a piece of his identity, or the essence of someone important to him. He’s not entirely wrong. Life is ephemeral, and objects can give us something stable to hold on to. But the world keeps moving, and stability can turn into just being stuck. Like Sam, we all have to consider: Which items enrich our lives, and which just take up all that space?

References:

|

Baillargeon, Michael. “Self-storage is on a growth kick.” REjournals, 30 Mar. 2022. Delmont, Matthew. “How a Hostile America Undermined Its Black World War II Veterans.” Dec. 2022. Feuer, Jack. “The Clutter Culture.” UCLA Newsroom, 1 Jul. 2012. Higgs, Kerryn. “How the World Embraced Consumerism.” BBC Future, 20 Jan. 2021. “Industrial Revolution.” Brittanica, 26 Sep. 2023. Lawrence, Quil. “Black vets were excluded from GI bill benefits.” All Things Considered, 18 Oct. 2022. “Plastics and American Culture After World War II.” PBS American Experience. “Rationing.” The National WWII Museum. “Salvage for Victory: World War II & Now.” The National WWII Museum. Sanburn, Josh. “America’s Clutter Problem.” Time, 12 Mar. 2015. “Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (1944).” National Archives. Stewart, Emily. “Why do we buy what we buy?” Vox, 7 Jul. 2021. “The Consumer’s Victory Pledge.” Hoover Institution. “Victory Garden at the National Museum of American History.” Smithsonian Gardens. White, Matthew. “The Rise of Consumerism.” British Library, 14 Oct. 2009. |