Toni Stone:

A conversation with author Martha Ackmann

Posted on: July 1, 2019

On June 15, 2019, Martha Ackmann spoke about Toni Stone with education dramaturg Ted Sod as part of Roundabout Theatre Company’s lecture series. An edited transcript follows:

Ted Sod: I read a biography of you that said that you were a tomboy and played baseball. Is that true?

Martha Ackmann: I played softball, but not very well. This was when I was about 12 or 13. I couldn’t run, I couldn’t hit, I couldn’t catch, but I could throw, so they put me in center field. It was a neighborhood team, but we didn’t have a sponsor. All the good sponsors—the hardware store, the dairy—had already been taken. But somebody knew somebody who knew somebody who had an uncle who ran a garden supply company called “Flexible Hose.” They became our sponsor and--let me tell you--when you run out to center field with “Flexible Hose” on your back, it’s a challenge to be much of a ball player.

TS: I’ve also read that you have written about sports for various publications. What is the interest on your part in sports?

MA: I grew up in a sports-minded family. We watched the St. Louis Cardinals baseball games or listened to them on the radio. I liked the game itself, but I also liked what it signified. Later on, I started writing pieces for The New York Times. The Times used to have a column in the Sunday edition called “Back Talk,” on the social significance of sports. As a nonfiction writer, I’ve always believed in what David Halberstam once said, “Behind every great sports story is the story of a nation.” If you think about Billie Jean King, Mohammad Ali, Jackie Robinson and others -- I think he’s right. When I went looking for the subject of my next book, I knew I wanted to write about sports because I love it and I know baseball best. At that point, the only thing I knew about Toni Stone’s story was one phrase: The woman who replaced Henry Aaron. When Aaron went to the majors -- he was a second baseman for the Clowns -- Toni replaced him. That’s all I knew. So I said, “I’ve gotta find out more about this.” And that began the process.

When I first started the book and I was in the preliminary stage of research, my big question was, is this a magazine piece or is this a book? Will there be enough material out there for me to find? Will her story deepen and resonate and mean more than the statistics?

TS: You’ve also written a book about the thirteen women who were being trained to be astronauts and then were summarily dismissed by NASA.

MA: That’s right. It’s a book called The Mercury 13. In the early 1960’s a group of hotshot women pilots were secretly tested to become astronauts along with John Glenn and Alan Shepard, and when they scored too well, NASA scrapped the program.

TS: I also want to ask about your interest in Emily Dickinson, because your book about her has a very specific point of entry.

MA: Yes, it’s a new book called These Fevered Days and it’s coming out in February. I’ve studied Dickinson all my life and at Mount Holyoke College I taught a course on Emily Dickinson – a seminar that I taught in the poet’s house in Amherst, Massachusetts. In the book I focus on ten specific days in her life – days that are chronological, but not consecutive. Something happens in the course of each day that changes her, where she’s different at ten o’clock at night than she was at ten o’clock in the morning. It might be a letter, a thought, or idea that is transformative. I crack open each of those days to take a look at what happened, trying to animate Dickinson as a living, breathing woman—not as an literary artifact trapped in amber. As a nonfiction writer, I’m bound by fact, so each chapter is grounded in letters, documents, diaries, newspaper accounts, even weather reports. The first chapter, for example, focuses on a day when she is fourteen and writing a letter to a girlhood friend. To my ear I hear her voice for the first time: cocky, good at language--someone who knows she has talent.

TS: We should talk about Toni. How do you write a book about someone history has forgotten?

MA: Sometimes the challenge is selling the book: when a publisher might say, “Nobody knows this person.” I always respond, “Well, that’s the point. That’s why I’m doing what I’m doing.” When you’re writing narrative nonfiction, you’re wearing several hats. You’re a journalist because you’re tracking down facts, you’re a detective because you’re trying to uncover details that are often hidden, and you’re a bit of a fiction writer in that you’re using the tools of fiction – character, setting, plot – to tell a true story.

One of my first Toni Stone research trips was to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. I didn’t find any of her stats, I didn’t find any information about her progression -- how she went from the San Francisco Sea Lions to the New Orleans Creoles and eventually to the Clowns. I did find one tape recording. It happened that I was getting ready to leave and the archivist said, “You might want to listen to this.” In the early 1990’s, the Hall had a salute to the Negro league players and had invited about fifty men to Cooperstown to be celebrated at a banquet. Hank Aaron was there. I listened to the recording and there was nothing, only people thanking everyone for the celebration, but then, all of a sudden I hear this odd high-pitched voice. Toni, when she was a kid, for some reason drank horse liniment and it changed her voice: it became very high and squeaky. She always said that when she wanted to be heard, she carried a whistle and a baseball bat. She knew she had a strained voice, which was so antithetical to who she was. But in this recording, I heard her voice. It was unmistakable. She sounds as if she’s standing up at the end of the banquet, wanting to be heard--yet again. She said, “Could I say something?” And then goes on to say, things weren’t always easy. Sometimes I got a pat on the back and sometimes I got a foot, she said. But she was grateful. “I had the opportunity to play with some of the finest guys in the country,” she said. “They thought I would leave and not come back ‘cause things were tough. Nuh uh. Baseball is my game. And I’m thankful!” That’s actually how I close the book.

When you’re writing a baseball book, people always want to know about the stats. But the thing about the Negro leagues is that the stats aren’t complete. Very often the pitcher was keeping the stat book and he’d be called in to pitch in the later innings and the stat book would be forgotten on the bench and they wouldn’t have stats from the sixth inning on. Or the club manager would have to call in the records to the newspapers, to the black newspapers because white newspapers didn’t carry Negro league news. And maybe they’d had a hard night, they couldn’t get to the phone, they didn’t call them in, so records are spotty. And that’s one of the reasons why many Negro leaguers aren’t in the Hall of Fame, because the records have been lost. Certainly many more Negro leaguers should be in the Hall.

To get back to your question about how I went about the research, I tried to collect as many of Toni’s numbers as I could, but I was running short on time, so I hired my nephews as research assistants. Christian and Jon read all the back issues from 1948 to 1955 of the Chicago Defender, the Kansas City Call, and other well-known black newspapers, photocopied every single page that had something to do with Toni, and sent them to me. I spread the pages over my dining room table and I went through them as best I could. I think, thanks to Jon and Christian, what we assembled is the most accurate record for Toni Stone anyone has ever put together. I should mention that my nephews were 12 and 13 years old at the time they were helping me.

I never interviewed Toni. She had already died by the time I started the book. I deeply regret I never spoke with her because in audio interviews I found, she was a great storyteller. I tracked down her teammates and umpires, even fans who saw her play. I spent a lot of time traveling from San Francisco to New Orleans to Norfolk, Virginia, interviewing older guys in their garages and basements and having them tell me what they remembered. I recall one guy, he actually provided the epigraph for the book, his name was Thomas “Tater-Buster” Burt. That’s another great thing, all the nicknames. He told me about how impressed he was with Toni’s determination, perseverance, skill and athleticism. We had finished the interview and I was getting ready to leave – you’ll always get your best quotes when you’re packing up to leave -- and I said to Tom, “What do you do these days?” He was in his 80s by then and he said, “I coach my grandkids.” I asked, “What’s the hardest thing for them to learn?” He said, “a curveball.” Not knowing how to hit a curveball myself, or what exactly he meant, I said, “What do you mean?” So, he said, “Stand up.” I stood up and assumed a stance and he said, “I’m gonna throw you a curve. The secret to hitting a curveball is you step into it.” I remember taking down that note and thinking about it. It took me about two-and-a-half years to write the book and I kept staring at that quote from “Tater-Buster” Burt. “You don’t step away from a curveball, you step into it.” Then it became clear to me that that phrase represented the larger theme of Toni’s life. Toni Stone was handed one imperfect chance to live her dream. And what did she do? She stepped into it.

TS: Had you been completely aware of how much sexism and racism Toni encountered or all women encountered at that period and probably still do? Did that encourage you to take on this subject?

MA: Most of the books I write have something to do with sexism or racism or the intersection of multiple forms of oppression. It didn’t come as a surprise to me that she had to fight and that she had to have a strong sense of herself, what she wanted to do. She was driven to do what she loved and always said she couldn’t do much of anything else; she realized there was the one thing she could do better than anyone.

Toni had a terrible experience in school because of racism. She didn’t see herself reflected in anything she was studying. She loved history. Before she played for the Clowns, she played for traveling semi-pro teams: guys in a station wagon traveling from town to town. She loved the experience because she could hear all those stories about playing ball. That’s history, but it wasn’t the history she was being presented in the classroom. She once said, “When I studied history in school, it was all Captain John Smith and Pocahontas, and we were cotton pickers.”

The history of the Negro leagues reflects the racism of our country: some teams were forced to wear grass skirts, paint their faces. There was a player who pitched in Pelican Stadium in New Orleans. He’d search the stands for his wife who came to games. She was so proud that he was on the mound and pitching. But she was seated behind chicken wire because black Americans were forced to sit in cages. How do you hit your best, run your fastest, see the ball clearly, when so much else bigotry surrounds you? Fans sometimes yelled at Toni, “Why don’t you go home and fix your husband some biscuits?”

TS: Toni’s mother, who we get to see in the play, cannot accept that her daughter wants to do something that she doesn’t think is appropriate.

MA: Toni really didn’t get flack from her family about wanting to play baseball. It was that they didn’t think she’d be able to support herself financially. It was really a class question. Was she going to be able to earn enough money to support herself? It was more about economics than gender.

TS: The relationship with Millie that is portrayed in the show -- this was a real thing. Toni couldn’t stay with the men when they were on tour. Correct?

MA: The story I was told is that the team pulled up to a boarding house in the Jim Crow south, and there were lots of places where a black team was not allowed to stay. There were curfews. The bus couldn’t be on the road after ten o’clock in some places. One night they pulled up to a boarding house and it was late, they players are dead tired and all the men get off the bus and Toni is the last one. The boarding house proprietor sees twenty men and one woman get off the bus and assumes she’s a prostitute. Toni was devastated that her teammates did not stick up for her. She had nowhere else to go, so she went to a brothel where she later said that she met “good girls” who took care of her, who gave her a clean place to stay, something warm to eat, and who even sewed padding into the inside of her uniform so she could take hard throws to the chest. The good girls then started following the sports pages and knew where she was playing. Toni developed an informal network of brothels throughout the south where prostitutes would meet her. Millie has one line in the play where she says to Toni, “You’re playing for all of us.” Every time I hear that line, it breaks my heart because it’s true.

TS: Could you tell us how this play version came about?

MA: I got a call from my agent and she said, “I have someone who is interested in your book.” I’d done a lot of press when Curveball first came out and I did some interviews for ESPN. Samantha Barrie, who is the independent producer of Toni Stone, is a fanatic about baseball. She had her mirror in the bathroom positioned so she could watch ESPN in the background. One morning she was getting ready for work, and she saw reflected in the mirror my Toni Stone interview. Samantha said, “I’ve got to get in touch with her.” She called my agent, we had a conversation. As a writer, when you option your work, you hope that your vision of the story coincides with the person who’s optioning it. I had an immediate sense about Samantha; I liked her and trusted her. She knew baseball was more than box scores. That’s what I believe too. She brought on Pam MacKinnon, the director, and Lydia Diamond, the playwright. I am one lucky duck to be connected with such a remarkable group of women. Ours is an all-woman creative team and I think this is the first American theatrical treatment of baseball that is entirely by women: producer, director, choreographer, lead actor, playwright and author. We’re very proud of that fact.

Audience Question #1: I am interested if there were other black women at that time who were not as famous, but who were working in baseball.

MA: Yes, Toni was the first of three. She played one season for the Indianapolis Clowns and was traded to the legendary Kansas City Monarchs, the team of Jackie Robinson. She did so well in the 1953 season that some people said she carried the Negro league on her shoulders, both as a player and as a gate attraction. Once Jackie Robinson integrated the major leagues, the Negro leagues had begun to lose their fan-base as more and more people turned to watching Jackie and Larry Doby in the major leagues. Negro league owners like Syd Pollack were looking for ways to continue to have African-Americans interested in the game. He took a chance on Toni and when she did so well, he said, well I’m going to bring in more women players. Toni let it be known she was not pleased to share the limelight and she was traded to the Monarchs. Syd brought in another second baseman, a woman from Philadelphia named Connie Morgan, and then a five-foot-two right-handed pitcher named Mamie “Peanut” Johnson. Peanut earned her name when a batter said she was as little as a peanut. Mamie died a couple of years ago. So to answer your question more directly, two more women joined the Negro league: Connie Morgan and Peanut Johnson.

If you’ve seen A League of Their Own, there’s one famous scene where players are warming up before a game and someone throws a ball to Geena Davis. It flies over her head and a black woman picks it up. The woman looks back as if to say, can I throw this back to you? And she does, firing back a mean strike. That scene is meant to suggest Toni, Connie, and Peanut Johnson. Peanut did in fact want to try out for the so-called League of Their Own, the All-American Girls’ Professional Baseball League, but it was segregated and they wouldn’t allow a black woman to play.

Audience Question #2: They say no matter how much things change, they remain the same. We saw how difficult it was for women back then to be in sports and now we have the women’s soccer team who cheered themselves on enthusiastically with every goal, which caused people to get negative toward them too. What is your take on that?

MA: I fully support women’s soccer and basketball. But here’s the thing – women athletes have to earn a living, and they’ve got to make more than they’re currently receiving. To do that, sponsors have to step up, and fans have to get behind the teams. It infuriates me to see stellar collegiate basketball players who make it to the WNBA, and who are not being paid adequately. It hasn’t been that long ago that women and men weren’t paid the same prize money in professional tennis. So we need equitable salaries and sponsorship for women athletes. In everything aspect of life, we need women to go as far as they possibly can and in whatever direction they choose to go.

Audience Question #3: Did Toni have any children and did she stay with her husband?

MA: Toni did not have children. Her husband, Aurelious Alberga, was a fascinating individual, involved in San Francisco politics and civic matters. Toni married late in life. I forget how old she was because she always lied about her age. Alberga was forty years older than Toni. Toni seemed to be most comfortable around older men. She was born in West Virginia and then grew up in the Twin Cities in St. Paul and she played for a while with the St. Paul Meatpackers League. She loved hanging out with older guys. Part of that may be because they didn’t appear to pose any kind of sexual threat. She had what I would describe as a difficult relationship with women. When she was growing up, girls made fun of her. If you are thinking Toni was a lesbian, I don’t think that’s true.

I regret that I could never get a complete beat on her relationship with Alberga Their relationship was rooted in respect and affection, I think. Was it romantic? I’m not sure. Toni’s story is clearly a love story. But it’s is a love story about work, what you love, what defines you, what you most love to do more than anything else in the world.

Toni and Alberga stayed together until the end of his life, which was at age 104. When he was in a nursing home, she visited him every day. I think that says a great deal about the tenderness, mutual respect, and affection between them. She was 75 when she died.

TS: I was curious about the scene where Alberga went to Woody after he roughs her up. Is that something you uncovered?

MA: Toni endured sexual harassment and possibly sexual assault, but she wouldn’t talk fully about it. I never uncovered an instance when Alberga confronted players who were giving Toni a hard time—but I think it’s possible. I love the wonderful line in the play that Lydia wrote where Alberga takes on an abusive player and says, “If that happens again, I’ll kill you, not because she can’t, but because it would be my pleasure.” Alberga did stick up for Toni and he certainly took her seriously as a ball player.

Audience Question #4: Earlier you said that you were trying to decide whether this should be a book or a magazine article. When did you know it was a book?

MA: To be honest, I don’t know that I ever made that decision. I wanted so badly for Toni’s story to be a book. But it is a matter of finding the material. Time and time again I came up against the way racism affects everything in our culture, including archives and what gets saved, remembered, and valued. There were many times when I didn’t find what I hoped to locate. Materials, memories, the past was lost. So I think I willed Toni’s story into becoming a book—a book about baseball, Jim Crow, and how far we’re willing to reach for a dream.

Audience Question #5: Why did they accept women in the Negro Leagues?

MA: It was a matter of trying to bring fans in. Once Jackie Robinson went to the major leagues and television came on the scene, there were more and more people who were following the white major league. Negro league team owners were trying everything they could to bring fans in. When Toni joined the Clowns, it was a gimmick and she knew it. But she also realized it was the best chance she would ever get to do what she loved. She went into it with her eyes wide open.

Audience Question #6: I love that in the play Toni was a very literal person. Is that true?

MA: Toni was single minded. She had a laser vision when it came to baseball. I think Lydia saw that orientation as a kind of literalness and spun it off in the play.

TS: Her logic is wonderful to behold, the way she breaks things down for herself.

MA: Pam MacKinnon, out director, said that Lydia Diamond has written a play that tells us about Toni’s life and her brain. In the play, we get inside Toni’s head. I think that’s wonderful.

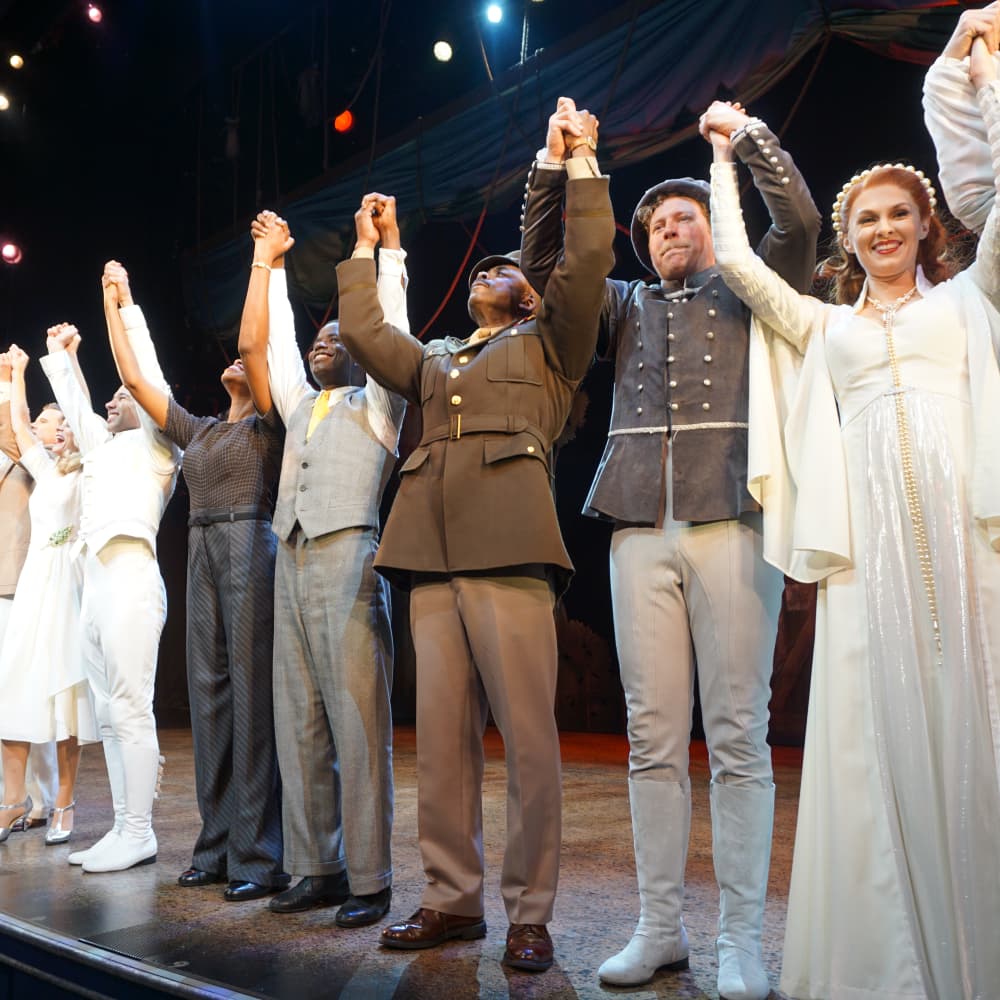

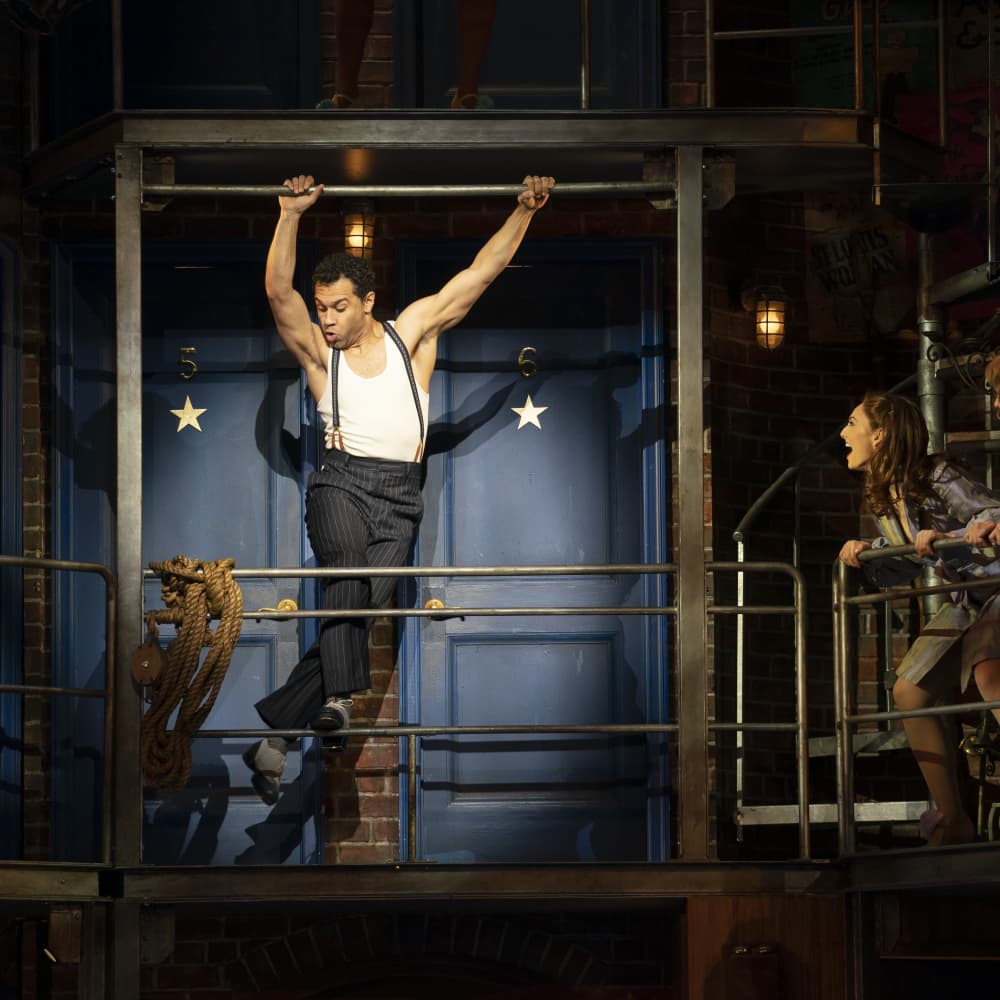

TS: It’s a true ensemble piece. Even though Toni is at the center, everyone fluidly moves in and out of every role, and then they collectively break into the minstrel moments.

MA: I’ve seen the play here at the Laura Pels nine times or more and I always watch the audience at that pivotal moment. The audience often applauds -- especially when Jonathan Burke as Elzie does those splits -- but then they recoil because they realize what clowning is really all about.

Toni Stone is now playing at the Laura Pels Theatre through August 11. Click here for tickets. For more information about our Lecture Series please click here.