Interview with Jack O'Brien

Posted on: April 24, 2019

Education Dramaturg Ted Sod spoke with Jack O'Brien about his work on All My Sons.

Ted Sod: Your memoir, Jack Be Nimble, is subtitled The Accidental Education of an Unintentional Director. How did you transform from being an unintentional director to an intentional one?

Jack O’Brien: I fell in love with Rosemary Harris and Ellis Rabb’s APA Repertory Company when I was at the University of Michigan. APA (Association of Producing Artists) was the resident theatre company for the brand-new professional theatre program there, and it was activated just about the time I went into graduate school. I’d never seen anything like them. I was just drunk with admiration and fealty, and I followed them everywhere. I matriculated to New York City shortly after I graduated, and they were in residence off-Broadway. I really pestered Ellis until he made me his assistant. For about six years, I was the only assistant they had and/or could afford, which meant I was taking the director’s notes for Ellis Rabb, Alan Schneider, Eva Le Gallienne, and John Houseman. I had a postgraduate indoctrination no one else in my generation had. I was submerged in this company that had residencies at the Lyceum Theatre on Broadway and in Los Angeles; Ann Arbor, Michigan; and Toronto as well. So by the time it was over, there didn’t seem to be any turning back. Houseman graciously invited me to direct at Juilliard, and around that time APA disbanded. I was tapped to direct the bicentennial production of Porgy and Bess. They wanted Hal Prince, but he was committed. The conductor, John DeMain, finally said, “There’s this guy that I think is really talented.” That was 40 years ago, and it not only created my career, but it introduced me to nearly 10 years of opera work. Opera directing commitments are at least five years in advance, and theatre’s trajectory is more like six to eight months. So, I took a chance and cut my ties and had 10 years refining my work on the road before Craig Noel invited me to work at The Globe Theatre in San Diego.

TS: You directed a television version of All My Sons in 1987. How did that come about? Was Arthur Miller involved in that version?

JO: One of my closest personal friends is Lindsay Law, who was in charge of programming American Playhouse on PBS, and he guided me into directing for television. We filmed All My Sons in Toronto. The cast included James Whitmore, Michael Learned, Aidan Quinn, Joan Allen, and Zeljko Ivanek. Arthur came up to Toronto to work with us, and he was simply wonderful. I had gone originally to meet with him to seek his blessing and his advice. He later professed it to be his favorite version of the play, and I never knew what this meant, but I took it as a compliment: he said, “It’s the most lyric production of the play I’ve experienced.” I was very proud of it. All My Sons is a great play. When we’re all dead and buried, rather than the more popular Death of a Salesman, I believe Miller may be most remembered for being the author of this particular play.

TS: It is, in fact, the fourth Broadway production. Roundabout has done it twice before Off-Broadway. Once, in 1997, directed by Barry Edelstein with John Cullum playing Joe. And earlier, in 1974, Gene Feist directed it with Hugh Marlowe as Joe. What do you think it is about this play that audiences respond to viscerally?

JO: Buried in that play is the DNA of who we were as Americans at the conclusion of World War II. We were struggling with our international reputation. We had come late to the defense of the most vulnerable countries in Europe. We played a key role with our incredible, almost naïve, positivism. It cost us dearly, but we took responsibility for what we did. I am referring to the Marshall Plan, where we forged our reputation for being not only citizens of the world, but also caretakers. That seemed to resonate with a young country that was proud, that had distinct values, that knew right from wrong and good from bad. We were a moral society and we were naïve; but it was real, and this play touches on all those issues to remind us who we once were and what we need to change in order to be better. I can barely get through the play without being overwhelmed. I think it’s profoundly touching, and it resonates within most of us because we see our parents, we see our grandparents, and we see the past from which we seem to have resolutely descended.

TS: Miller is a brilliant craftsperson in terms of how he interweaves all these characters and their histories. I keep thinking about the denial in the play. It’s so present for me: the mother’s denial, the father’s.

JO: Oh, God, yes. We’re all culpable in that aspect.

TS: I wonder if the themes of the play will resonate with an audience in 2019.

JO: I’d be very surprised if they didn’t. First of all, as you say, it’s brilliantly written. It’s just a stunning piece of craft, but it’s truly about us as Americans. At the moment, we don’t seem to want to own up to being responsible for each other. We would rather be either cynical or step away and be selfish, greedy. We’re bloated and we’re basically turning our backs on the inherent philosophical bent of the American spirit. I think the play uncovers that and asks you to take a stand, frankly. What we learned when we did the play for television, and what I’m about to go through with this new group of people, is that it’s a bit of a mystery play. You have to know who knew what and when they knew it in order to figure out how events like the ones divulged in the play could have happened. I have such respect for what Miller wrote. My only concern is to get that onto the stage. It’s not something you need to interpret. It’s not something you need to apologize for or, in the worst possible phrase, make relevant. It is relevant by the fact that it’s the handiwork of one of our greatest writers and it just needs to be heard as honestly as possible.

TS: What kind of an atmosphere do you create in the rehearsal room? Can you give us some insight into your process as a director? How do you collaborate with actors?

JO: It’s a complicated thing to describe, but basically I like to stay out of the way as much as possible and listen to the actors, respond to them, edit them. I think of myself as their first audience. I’m not a dictatorial director at all. I like to create an atmosphere of inclusion where everyone gets to express what they feel and think, and we evolve from there.

TS: Do you have history with other Miller plays? When you were at The Old Globe, did you direct any plays written by Arthur Miller?

JO: No. Mark Lamos directed Resurrection Blues at The Old Globe just before I left as artistic director. I thought it was a wonderful production. For American Playhouse, I also directed Arthur’s adaptation of Ibsen’s An Enemy of The People. Miller’s work has a very strong moral code, and being responsible for your actions and owning them is something we’re not really good at these days.

TS: How are you collaborating with your design team?

JO: I reached out to the very same team that did such an exemplary job with the production of The Sound of Music I directed recently. We know each other well, and we had a wonderful time working on the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, so it’s a joy for us to be able to get back together. We’re doing it as faithfully to the period as we possibly can.

TS: Will there be original music?

JO: Yes. Bob James, who has been a frequent collaborator of mine, is composing original music for this production. He also did the scores for Stoppard’s The Hard Problem as well as Two Shakespearean Actors and The Invention of Love, which were all done at Lincoln Center.

TS: Do you have any advice for a young person who says they want to direct for the stage?

JO: In order to be a director, you have to be a lot of other things first. I think it’s the last thing you do, because you are basically the overseer. I think you back into directing. One needs to experience all the elements that go into putting a play up in front of an audience first. I also believe that if one seriously wants to have a career directing, get the hell out of New York.

TS: Is there a question you wish I had asked about the play, your career, or about Arthur Miller that I didn’t?

JO: No, I don’t think so. I’m in the honorable position of having something that I feel very strongly about fall suddenly and fortuitously into my hands. I’m grateful for it and eager to get started.

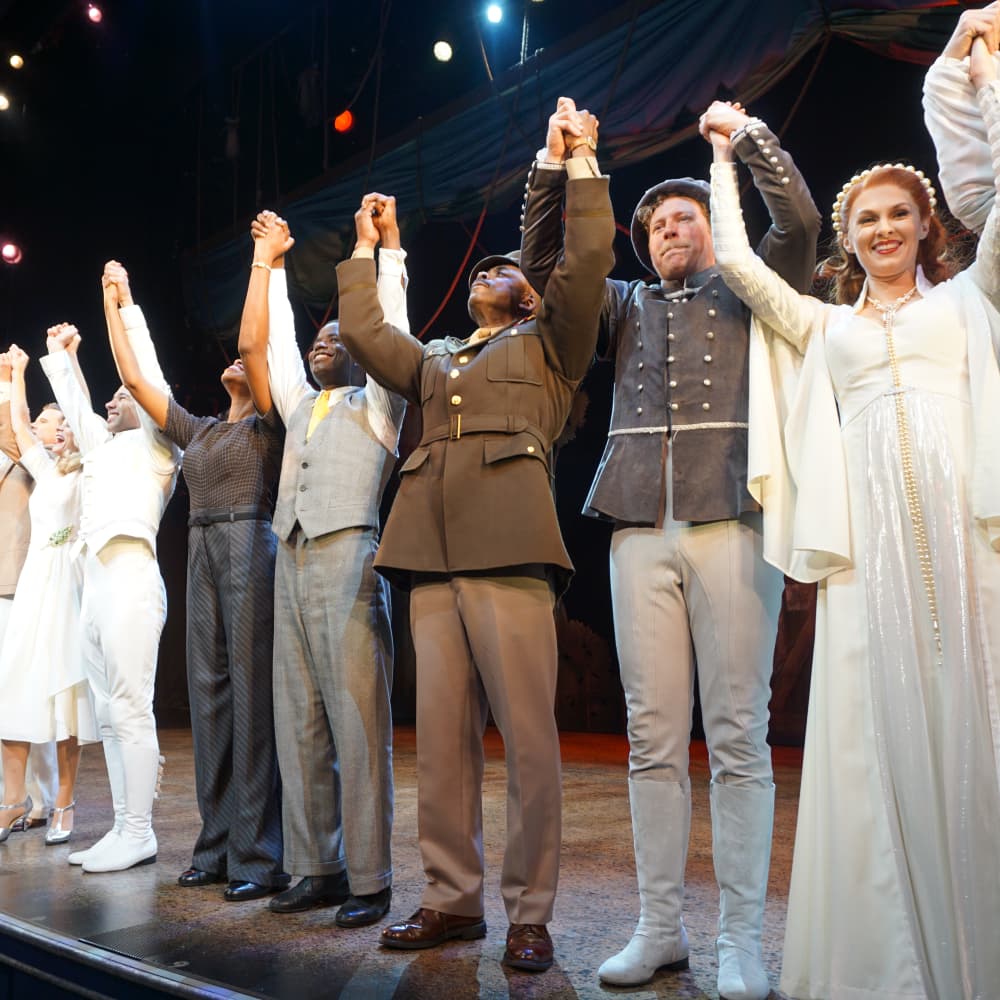

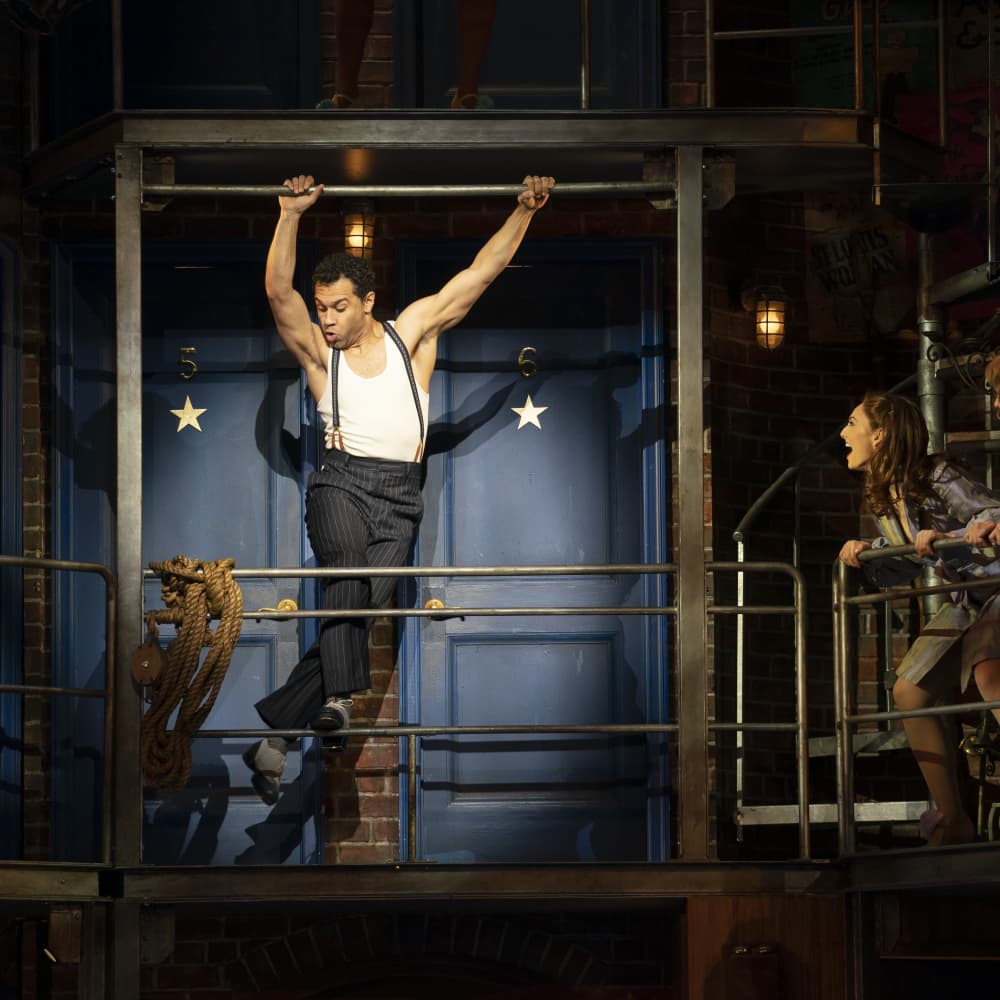

Arthur Miller's All My Sons is now playing at the American Airlines Theatre through June 23. For tickets, please visit roundabouttheatre.org