Merrily We Roll Along :

Present in the Past: What Makes Theatre Theatrical

Posted on: February 13, 2019

Columbia@Roundabout is a collaboration between Columbia University School of the Arts and Roundabout Theatre Company which provides exceptional educational and vocational opportunities for the next generation of playwrights and theatre practitioners.

The program includes an annual reading series for Columbia MFA students, Teaching Artist training facilitated by Education at Roundabout and two fellowship positions in Roundabout’s Archives.

As a part of the Archives fellowship, the MFA candidates conduct deep research into our historic records and are encouraged to produce scholarship that explores Roundabout’s contribution to American theatre. James Monaghan is one of the first Archives Fellows. Over the course of the coming months, James will write a series of articles about Roundabout’s production canon.

Let’s have a new conversation about theatre. Think back to the last show you saw that you really loved. After the final bow, what were people talking about? Maybe there were comments on a particular actor, a moving moment of dialogue, or the director had a brilliant bit of staging. We trust ourselves to be the critic of these elements of theatre, to decide for ourselves who we think is talented or what stories we are interested in. But, when it comes to most other elements of production: set, lights, sound, costume, projections, the space itself, our vocabulary is limited.

The purpose of this series of essays is to begin to open the idea that design is not extra; that it is a crucial element of what makes theatre, Theatrical. I want to encourage audiences to see all the aspects of a production and how they are working together – or not. Let’s dive deeper than spectacle for spectacle’s sake. Design does more than create an image that is nice to look at or impressive in scope. It does more than help us understand setting. The characters on stage and the words they are saying are just one way the story gets told. Through Roundabout’s Archives, we can take a closer look at design elements and test the idea that theatre isn’t quite Theatre without considering design.

“Theatrical,” like “site-specific” or “immersive,” is a term that gets thrown around frequently in theatre conversations. But over-use over time tends to generalize meaning rather than clarify it, especially with an idea so abstract to begin with. Is every moment of a performance in the theatre inherently “theatrical?” To get us started, I’ve pulled a few specific moments from Kneehigh Theatre’s production of Brief Encounter (Roundabout 2010) and Fiasco Theater’s production of Into the Woods (Roundabout 2014) where the design elements and performers combine in a very specific way to see if we can capture theatrical lighting in a bottle. Let’s start with what “theatricality” isn’t. Flashy lights, massive sets, and mechanization are spectacular, but in many cases are intended to “wow” the audience more than tell the story clearly or in a more nuanced way. Of course, this isn’t a universal truth—there are certainly times when elaborate, flashy moments are helping to tell the story. For example, the revolve in Bernhardt/Hamlet that turned the entire set between scenes could’ve easily just been for “oohs” and “ahhs.” Instead, as the world turned, we got a private glimpse into a character preparing to enter a scene or recovering from it—a private, backstage moment put in front of our eyes because of the design elements. But generally, theatricality uses less to suggest more.

Four theatrical Ideas (an incomplete list)

1. Audience

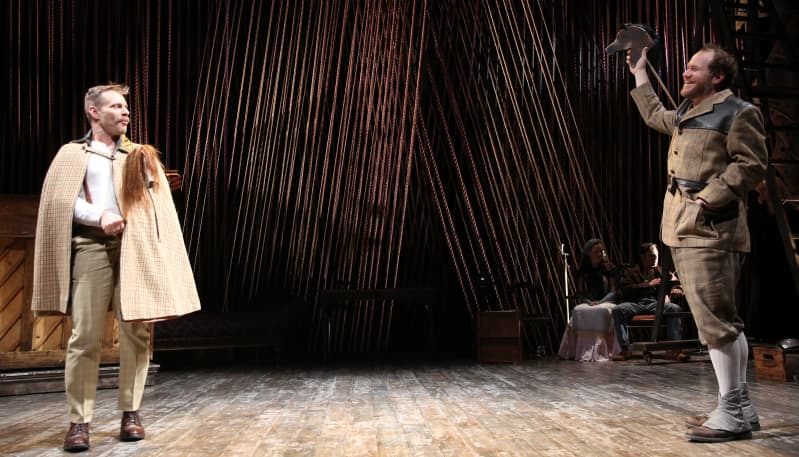

- In a fairy tale land, two pampered princes search for their missing damsel in distress. In the middle of an agonizing search, they pause to pass their faithful hobby horses to two people in the front row. This almost always provokes laughter—I think because it reminds us of the fiction. The audience is a group of people sitting in the dark watching a play, but they are also invested in this effort to find two maidens and stop a giant.

2. Gesture

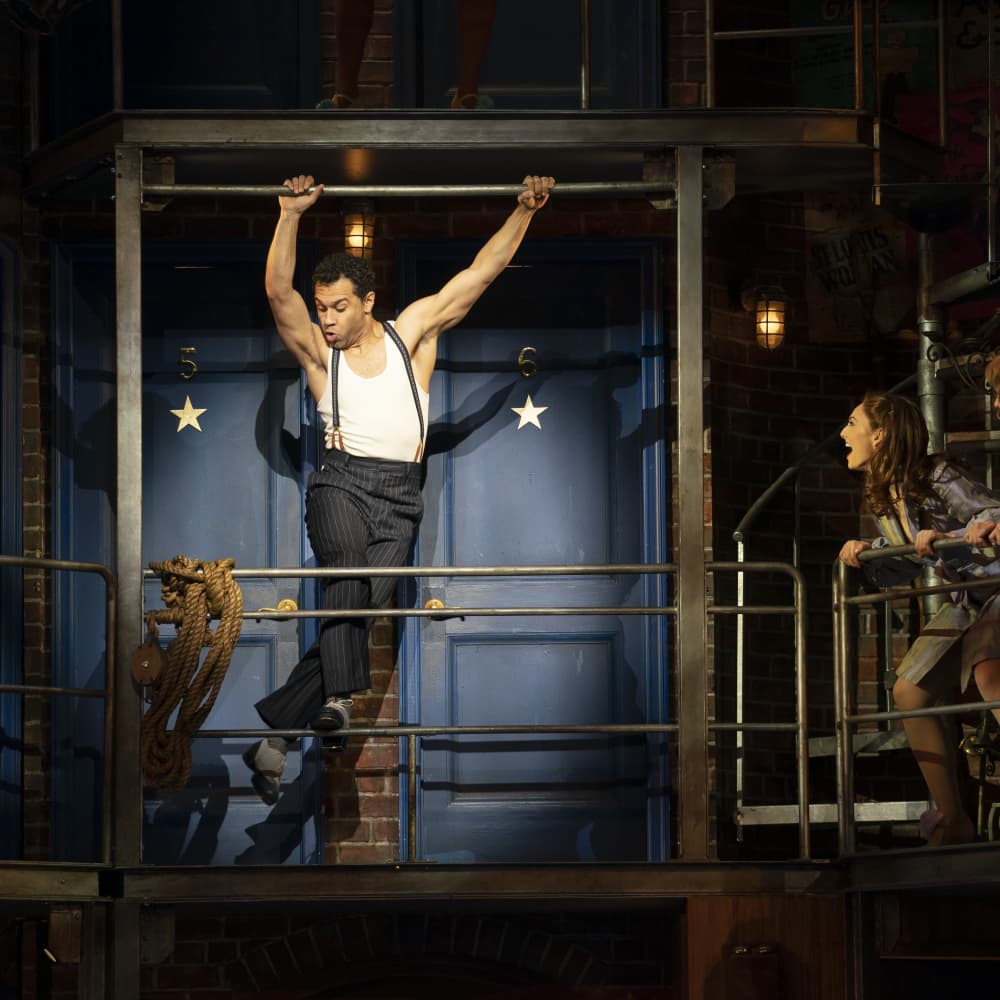

- At a small cafe in London two forbidden lovers, both in loveless marriages, long for some way to escape and to express their feelings for each other. They could try with words, but with a physical gesture, they are literally swinging from the chandeliers. This gesture makes hidden internal feelings, visible and visceral. She makes him feel like he can fly and he, her—and in this world, they can.

3. Dilation

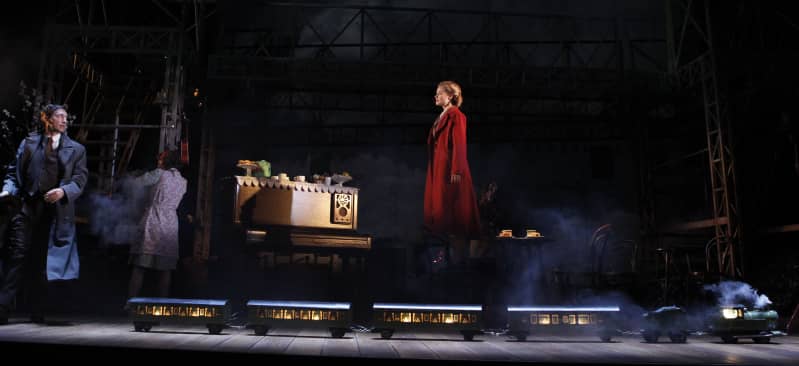

- In an earlier encounter, these doomed lovers are pulled apart by prior obligations—he must catch the next train. How to show this? Exit through a door marked “Train” or a more theatrical choice? A conductor guides a toy train, complete with smoke stack and lights in the passenger cars across the stage. The outbound lover falls in step and the one left behind waves from the platform. Our imaginations fill in all the missing pieces.

4. Transformation

- A young woman has lost her mother and is tormented by her father’s new wife and her wicked step sisters. Every day, she sits under a tree near her mother’s grave. This could be shown with a tombstone and some branches or, a wiry mannequin in the form of a woman can be lifted, endowed by the young woman with the emotional significance of a lost parent, and we understand instantly what the girl feels and what she sees when she looks at the tree.

In brief, theatricality is the performance of imagination – it requires a precise alchemy of design and performer to trigger an imaginative leap in the minds of the audience.

All photos by Joan Marcus.

Want to see Fiasco Theater in action? Check out the re-imagined production Merrily We Roll Along now playing the at the Laura Pels Theatre through April 7th. For tickets, please visit roundabouttheatre.org.

Want to reach out to James? Contact him at jamesm@roundabouttheatre.org