Kiss Me, Kate:

A conversation with Paul Gemignani, music director of Kiss Me, Kate

Posted on: March 21, 2019

On March 9, 2019, Paul Gemignani spoke about Kiss Me, Kate with education dramaturg Ted Sod as part of Roundabout Theatre Company's lecture series. An edited transcript follows.

Ted Sod: Let’s start with just a little history about Kiss Me, Kate. The inspiration for this musical came from a producer, Arnold Saint-Subber. He was the stage manager on a production of The Taming of the Shrew that starred Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne. He was shocked that they would fight in character as Kate and Petruchio onstage and then come offstage and keep fighting as themselves. It was his idea to create a musical that married the warring offstage of a famous acting couple with the warring in the musical play they were performing. Saint-Subber was a smart producer. He hired Samuel and Bella Spewack to write the book. They were a married couple who were separated at the time. They had already written a popular play entitled Boy Meets Girl. Bella supposedly did the bulk of the work on Kiss Me, Kate, but she loved working with her husband and evidently, even though they were separated when they started working on this show, they got back together by the time it opened. The story goes that they had to fight for Cole Porter. He was not considered a bankable composer at the time because he had had a few flops, but Bella fought for him. She said that he was the only composer who could write the score with wit and romance, which she knew the storytelling needed.

Paul, this is the second time you’ve music directed Kiss Me, Kate. How much time do you usually get to work with the performers on a revival like this?

Paul Gemignani: Six weeks sounds short, but Warren Carlyle, Scott Ellis and I have done many shows together -- so we’re organized. Just like any job, if you’re organized you can get it done. Also, we have cream-of-the-crop performers here. It starts out with me teaching all the music in a day or two during the first week of rehearsals. The principles usually come and they already know their music. That’s new. That never used to happen. You used to have to teach everybody everything from scratch. These days, you teach them once and it sticks. Yes, you finesse it and correct your own mistakes, but these performers are professionals. They know what they’re doing. Once that initial teaching happens, I don’t really see them again. I move on to the orchestrations and then to supervising.

I bring the orchestrator in really early on, so he’s not thrown. Larry Hockman did the orchestrations for this revival and he is a genius. You can talk to him in terms of colors and images and reasons for things to happen as opposed to just musical notes. And his ability to work that way is really great for choreographers and directors who don’t always have a musical vocabulary. This show has 4700 bars of music in it, which Larry orchestrated in less than three weeks. I give Larry at least 91% of the credit for making this show sound the way it does.

Throughout the rest of the rehearsals and tech, I put my time into watching rehearsals, making sure Warren, the choreographer, and Scott, the director, are getting what they want. I act as a supervisor, making sure everyone is happy, taking care of the ensemble, ensuring that they’re healthy by reminding them how to take care of their voices if they don’t already know how to do that.

TS: How long before rehearsals started did you know you would be involved with this show?

PG: I knew about six months before we started. I got called to do the concert version two years ago, but I couldn’t do it because I was working on a film. I thought whoever did the concert was going to do the show. It just so happens that the person who did the concert version is Hugh Jackman’s musical director and he got busy and suddenly my phone rang. That was lucky for me.

TS: Isn’t one of the music director’s jobs to make sure that the composer and lyricist are happy with the way the music is being interpreted?

PG: Dead or alive. It’s easier when they’re dead. I feel that a huge percentage of my job is to protect Cole Porter. I don’t mean the other two people on the creative team won’t. I just mean I feel more responsibility for Mr. Porter than maybe they do. I take that responsibility seriously. And we’re dealing with an estate that is very hands on – they check every change of lyric, every word, every musical note, every cut. I think that’s great.

I think it’s so important to revive this period of musical theatre. The Met keeps doing Carmen and La Boheme over and over and everyone comes to see them. Shows like Kiss Me, Kate, She Loves Me, A Little Night Music -- we don’t have an institution that presents these significant works, except for Roundabout. This show was written in 1948 and it’s only had one revival before this one in 1999. So, for students of theatre or just people who love musical theatre, it’s very important that these works get done – otherwise, everyone will forget about them. Yes, doing shows like this is more of a challenge, mostly because you have to tailor them to what audiences will accept nowadays. You might have noticed how fast-paced the show is. You might have noticed the overture is gone, the entr’acte is gone, there are little cuts in the script and there’s a reason for that. Audiences won’t sit still.

TS: Kiss Me, Kate won the first Tony Award ever given for best musical in 1948 and wasn’t revived for 50 years. Why do you think that is?

PG: When you think about it, from 1950 on was a very rich time in musical theatre. You had big shows like Fiddler On the Roof, Sondheim started to write amazing work directed by Hal Prince in the 1970s. The only thing that would get revived then would be a Rodgers and Hammerstein show. What I think has happened is that since the modern musical has come about, people crave this kind of musical. There’s no real romance in most of the newer works and I think that shows like Kiss Me, Kate are coming back because of that. There’s a need for the heightened language, romance and this style of storytelling. The way the creators of this musical incorporate Shakespeare into their story is genius. It becomes the language of the show and the audience doesn’t even know it. Suddenly the characters are speaking Shakespeare’s lines and by the time we get to the end of the show, everyone knows what they’re talking about.

TS: You music directed the 1999 revival with the late Marin Mazzie and Brian Stokes Mitchell. How did that version differ from this one?

PG: When you do a revival, it’s hard to do the same thing you did before. There are two different people playing the leads sitting in front of me singing, so why would I force them to do something that somebody else did? This version is completely rethought. Of course, there are similarities, it’s the same play, it’s the same music, but it has been completely reconceived because every performer brings something different to the process.

TS: You’ve mentioned how much you love being up in the boxes here at Studio 54 because you’re able to see the entire action in the show as opposed to being down in the pit.

PG: The orchestra being in the boxes was first done when I worked on the revival of Assassins here in 2003. They originally wanted the orchestra to be backstage and I’m somebody who won’t work on a show if you’re going to put me backstage. Orchestras are not supposed to be backstage. They are supposed to be seen. Joe Mantello was the director on Assassins and I said, “Okay, Joe, if I find a place to put the orchestra that’s not backstage, will you do it?” I tried sitting on the orchestra floor, taking up two rows of seats. Can you imagine a producer giving up two rows of seats? That wouldn’t have worked anyway because no one could get low enough and anyone who sat behind us wouldn’t be able to see. As a last resort, I was going to put the orchestra up in the balcony. I saw a European production of Cabaret that put the band up in the balcony, so I went up to the balcony and was looking around. At that time, the boxes here had doors and you entered from the balcony rather than from a stairwell in the orchestra. I went in and a bunch of junk was in there -- old chairs and stuff they didn’t need. And that’s how the boxes came to be. The first time we did that show, we would get up in the boxes and they would sway. Roundabout eventually built these steel structures to make them sturdier. What I didn’t know or anticipate was how incredible the acoustics are here. If you look up at the ceiling, there’s a European opera ring up there because Studio 54 was built to be an Opera House in the late 20s. This arrangement works so beautifully, acoustically. I’m just trying to make the boxes a little bigger now, so that we can get a few more musicians in there.

TS: When did you know who you wanted to be in your orchestra?

PG: I pick the orchestra first for musicianship. The first quality someone has to have to be in this orchestra is to be able to play extraordinarily. I hire a musician because I love the way they play, or I heard them somewhere, or someone recommended them and they came in and subbed and I remembered them. There are three or four people who have been with me for over 20 years. I also feel responsible for young people. The whole band shouldn’t be a bunch of old guys and girls. When I first started conducting there were no women in the orchestra. I started adding female string players in A Little Night Music. And everyone asked, “Well, how come…?” And I said, “Because I want it that way.” That’s what you have to do. It’s not a big deal. You just have to invite them and let them play The women in the orchestra inform the sound of the orchestra and I don’t just mean on the harp. Women in the orchestra make a whole difference, especially the string section. Sylvia D’Avanzo is one of the best players in town, if not the country. She’s is the first violinist who plays the solos. All the people up there are soloists in their own right. That’s a string quartet that carries the whole string section. It should be minimum 8 violins, 3 violas, 2 cellos. I have 2 violins, a viola, and a cello. So they have to be top notch. It’s artistry first and anything else second.

TS: Some music directors use contractors, but you don’t?

PG: There used to be contractors that hired musicians for the conductor, but the guy I worked for early on didn’t do it that way. He taught me to do it this way, which is much better. You hire your own people.

TS: Did you know you would be a character in this piece? That they would be calling you by your real name?

PG: I knew that in the show they talk to the conductor. I didn’t know they were going to address me.

TS: Is that fun for you?

PG: No. It’s just something I have to put up with.

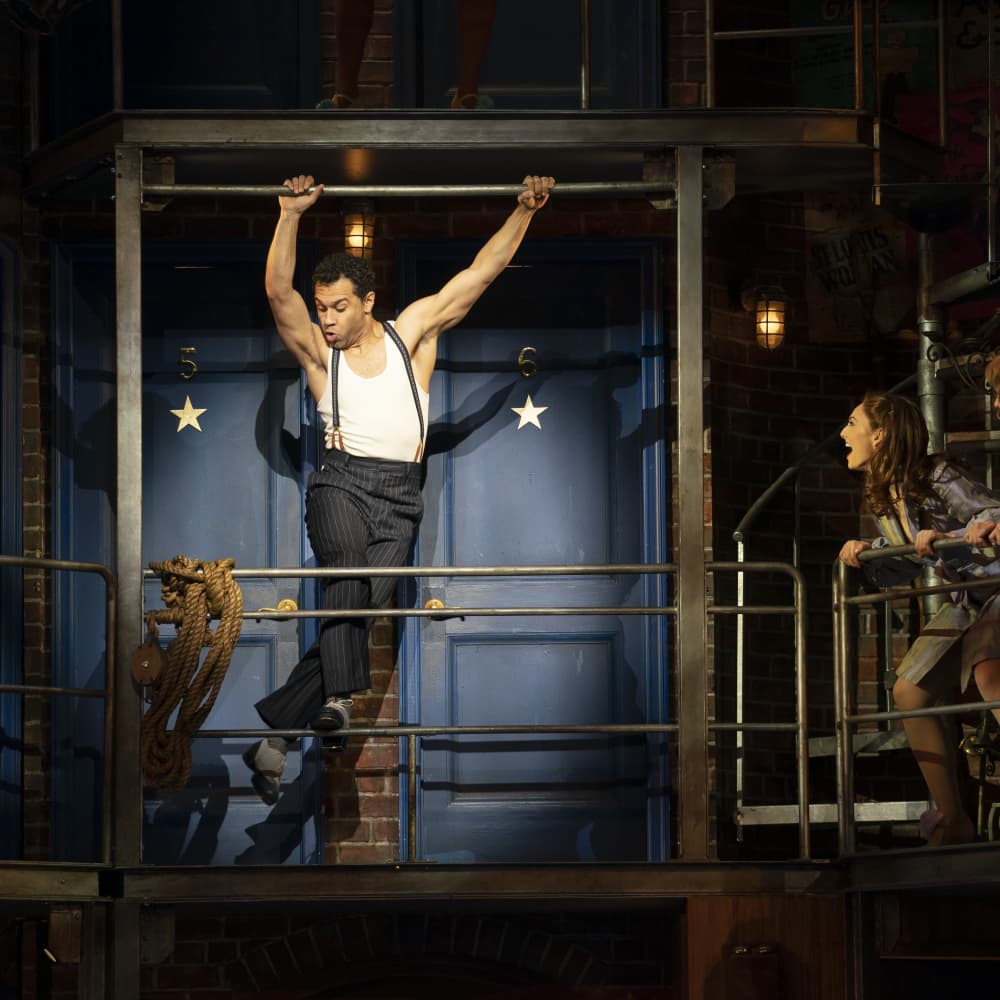

TS: How did you select Greg to be the musician who plays onstage in “Too Darn Hot”?

PG: I knew he could walk around doing different things and still play.

Audience Question #1: If the conductor is on one side, how do the musicians on the other side see?

PG: Through the miracle of technology. Except for the strings who are right in front of me, all the musicians have little five-inch monitors that sit on their music stands. And there are monitors for the actors on the balcony rail. They don’t use them because I train them to sing on their own.

Audience Question #2: Cole Porter is integral to the American Songbook and to jazz. I thought what was remarkable was the marrying of classical sound into jazziness. Was that purposeful?

PG: Absolutely. He didn’t write “Too Darn Hot” to be square. He didn’t write “Tom, Dick, and Harry” to be square. The guidelines in this show are so clear. That’s why you hear Elizabethan sounding orchestrations here and there. I thought, well we’re doing Shakespeare now, we can’t be playing 1940s dance music. In the 1940s, piano was not played like it was later in the century. You didn’t hear the piano playing rhythm. It’s more like Count Basie. You hear the harmony on the piano. In a show like this, the piano is used to comp, which means to play little fills and enhance a run. The rhythm section is guitar, drums, and bass. And that’s what we have up there. That was the whole idea in the ’99 revival, too.

Audience Question #3: What was the decision-making process in changing the lyric from “I am ashamed that women are so simple” to the universal “I am ashamed that people are so simple?”

PG: The sarcastic answer is that the Cole Porter estate didn’t care if we changed Shakespeare. They were very willing to let us do that. We agonized over how we would make that lyric change. It’s very important to this version of the show. The reason why we did the ending that we did is because it’s very difficult to not include how society works today in any revival of a musical you do. The ending that you saw today has only been in for a week. We had been doing the conventional ending. Scott always knew in the back of his mind that we needed to show Fred and Lilli by themselves.

TS: There’s been so much press about Amanda Green, the daughter of Phyllis Newman and Adolph Green, who was brought in to look at the piece, not to reinvent the wheel, but to make sure it worked with current sensibilities. The raison d'être for the lyric change that made complete sense to me was when Scott, the director, said, “I want my 9-year-old daughter to see this and I don’t want her to feel like a woman always has to capitulate.” I think that’s really what’s behind the change.

PG: Yes, we changed up and focused “I Hate Men” a bit too. She’s not just screaming and throwing dishes. She’s talking to the audience. That’s another moment where we tried to put Kelli’s character forward in a different light. And Kelli wanted it that way.

TS: I love the fact that Lilli is on this journey of self-discovery because we know how hard it is for a woman to be in this business.

PG: Any business.

Audience Question #4: Is the score the same as the original 1948 score? Has anything changed?

PG: “From This Moment On” is in the score now because Ron Holgate, who played Harrison Howell in the 1999 revival, would not take the role of the General without a song, so now it’s stuck in there. I can’t tell you why we did it. It wasn’t written for the show.

TS: “From this Moment On” is from a Cole Porter musical entitled Out of This World.

Audience Question #5: What was it like working with Kelli O’Hara?

PG: She is exactly what you’d think she’d be. She’s a perfectionist. You don’t hear a voice like that in the theatre every day. She’s a team player and a lot of fun.

Kiss Me, Kate is now playing at Studio 54 through June 30. For tickets, visit roundabouttheatre.org. For more information about our Lecture Series please click here.