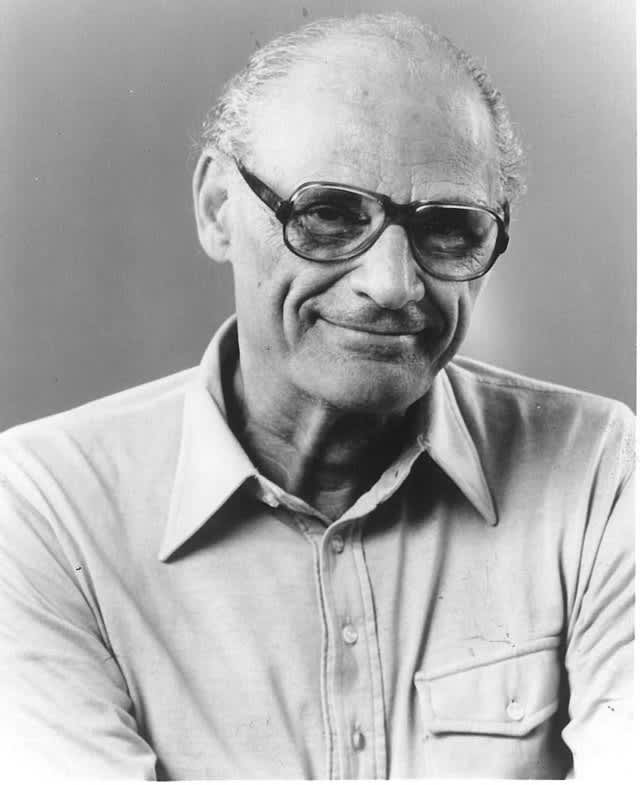

Arthur Miller's All My Sons:

An Introduction to Arthur Miller

Posted on: May 6, 2019

Miller’s Early Life

Arthur Miller was born in October 1915, on West 110th Street in New York City, to parents of Polish-Jewish descent. His father Isidore, an immigrant who never learned to read, had risen from traveling salesman to prosperous coat manufacturer, and his mother Augusta was an avid reader and educator. Prior to 1929, the family—including Arthur’s older brother and younger sister—lived comfortably, and young Arthur was driven in a chauffeured car. But the stock market crash and the Great Depression changed everything. The Millers moved to Brooklyn, living in drastically reduced circumstances, experiences that would influence young Arthur Miller and inform many of his plays.

Miller attended James Madison High School and graduated from Abraham Lincoln High School in 1932. After high school, he worked odd jobs, including carpenter, delivery boy, and clerk for an auto parts warehouse, to save for college. He attended the University of Michigan, where he wrote for the student paper and majored in English. There Miller was mentored by playwright and professor Kenneth Rowe, who taught classic plays and their dramatic structure. In 1936, Miller won the school's Avery Hopwood Award for his first play, No Villain. The $250 prize helped him pay for school and encouraged him to pursue playwriting.

The War and Miller’s Writing

After graduating in 1938, Miller returned to New York to write radio plays for the Federal Theatre Project. He married Mary Slattery, his college sweetheart, in 1940. When the United States entered World War II in 1941, Miller was declared unfit for combat due to an old football injury. His brother, however, was drafted. Miller remained in Brooklyn, writing by day and repairing ships at the Brooklyn Navy Yard by night.

Miller took notes on the laborers he worked with and featured them in short stories like “Fitter’s Night” that framed them as “heroes,” pondering the men’s role in the broader war effort. His war-related writing continued when Miller received government and Hollywood contracts to work on the 1945 film The Story of GI Joe, a dramatization of war correspondent Ernie Pyle’s front-lines columns.

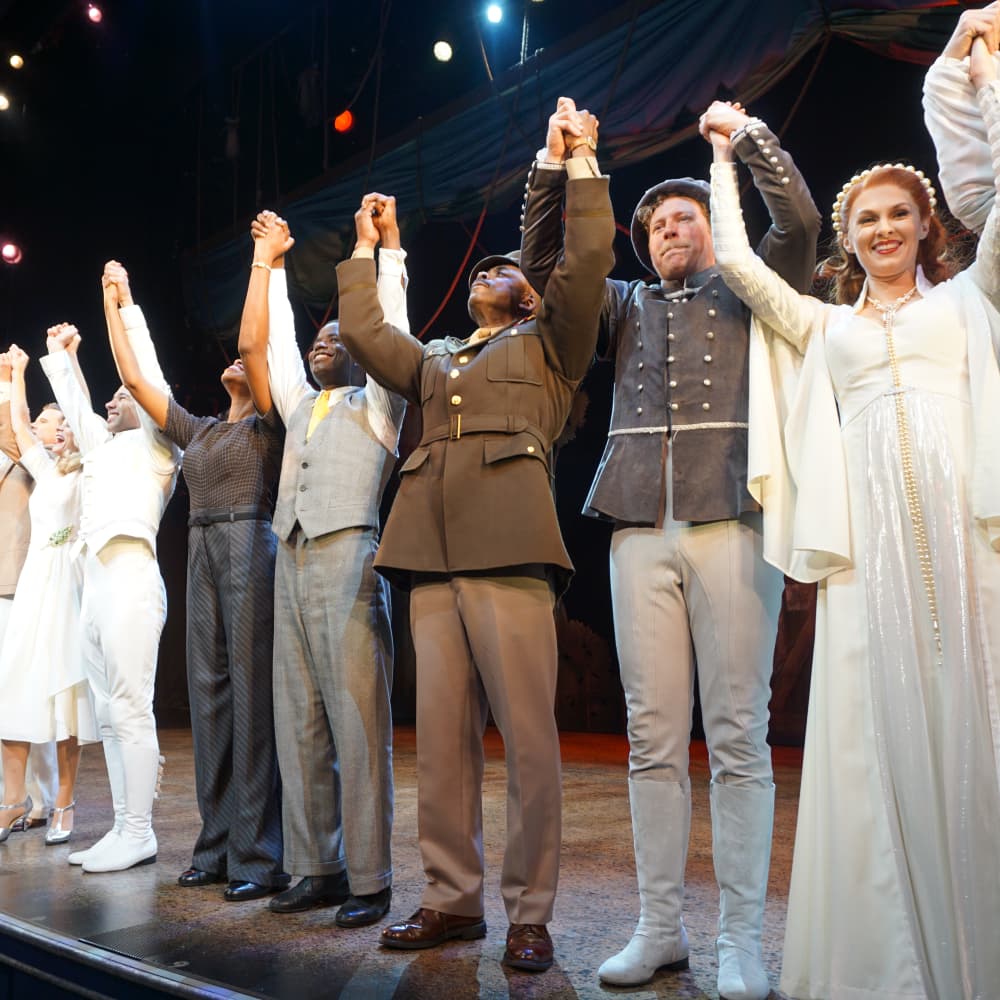

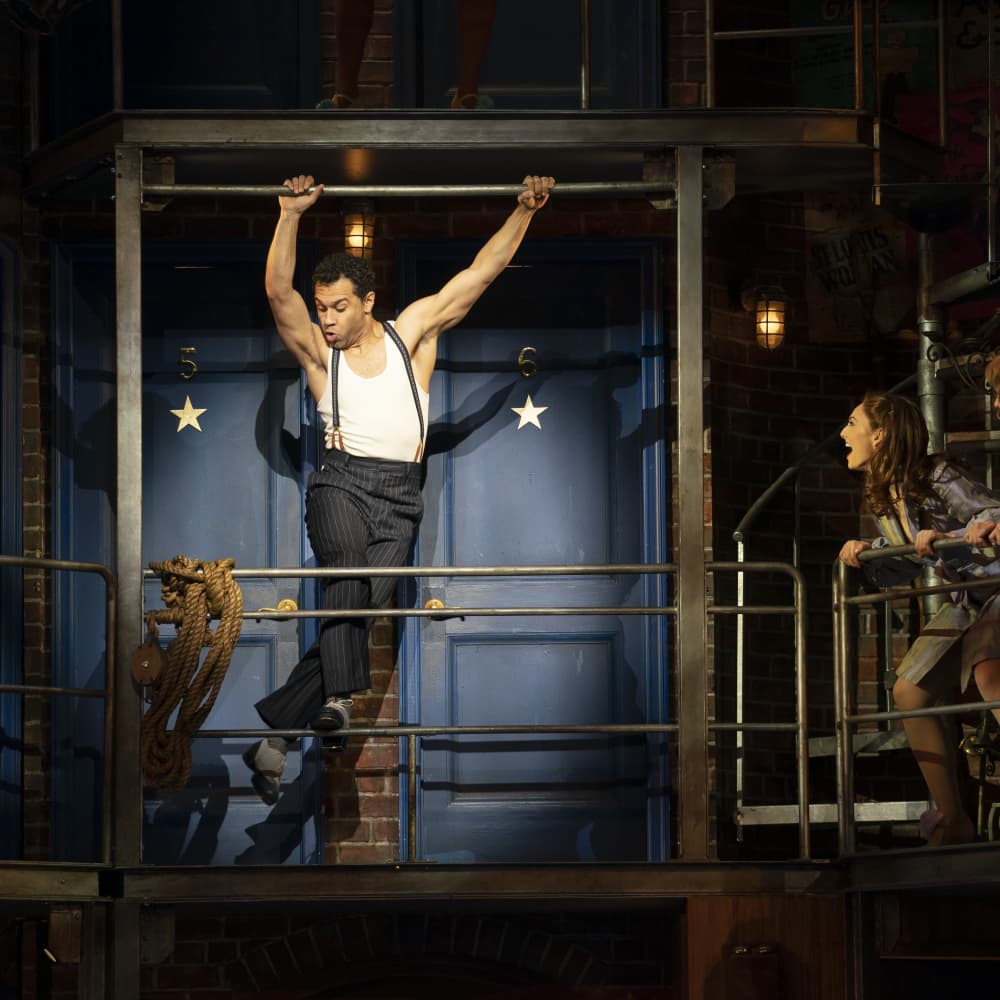

Although Miller’s 1944 Broadway debut, The Man Who Had All the Luck, closed after four performances, he hit the bigtime in 1947 with All My Sons. Influenced by Miller’s time on the Navy Yard and research into the lives of soldiers, this tragedy resonated with a war-weary, Depression-pummeled nation. It ran for almost a year and earned Miller his first Tony Award for Best Author.

Miller next wrote Death of Salesman. His creation of Willy Loman, an aging salesman confronting his own failure, resulted in an American masterpiece. Under the direction of Elia Kazan (who had also directed All My Sons), Salesman premiered on Broadway in February 1949 and won the Pulitzer Prize, the Tony Award, and the Drama Critics’ Circle Award.

The Crucible and Government Criticism

With The Crucible in 1953, Miller dramatized the 1692 Salem witch trials as an allegory for McCarthyism. Miller wrote the play as a rebuke against Kazan, who had betrayed mutual friends by naming them as Communists to the House Committee on un-American Activities (HUAC). Although the original production was not as successful as his previous plays, it has since become one of Miller’s most frequently produced plays around the world. When Miller himself was called before the HUAC in 1956, he refused to “name names” and was cited for contempt of Congress. The ruling was overturned two years later.

Monroe, Morath, and Miller’s Later Work

Miller initially met Marilyn Monroe in 1951 through Kazan, who was dating her at the time. Their friendship turned into a romance, and in 1956, Miller divorced his first wife to wed Marilyn, hailed by Norman Mailer as the union of “the Great American Brain” and “the Great American Body.” Throughout their marriage, Monroe worked steadily while struggling with addiction and personal problems, but Miller wrote very little. An exception was his screenplay for The Misfits, penned for Monroe. Miller and Monroe divorced in 1961, and she died of an overdose the following year.

Though the next few decades did not yield the hits of the postwar years, Miller remained a presence in the theatre. His 1964 play After the Fall was thought by many to have been inspired by his marriage to Monroe; however, Miller denied this, stating, ''The play is a work of fiction. No one is reported in this play.” Miller reunited with longtime collaborator Elia Kazan for its premiere. Other works included Incident at Vichy, The Price, and The American Clock (inspired by his family’s experiences during the Depression). He also scripted the 1980 TV movie Playing for Time, based on the true story of Jewish musicians in an Auschwitz orchestra during the Holocaust.

Outside of the theatre, Miller worked for the rights of international writers as president of PEN International. He spoke against the Vietnam War in 1965, participated locally in Connecticut politics, and served as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1968. Miller married Austrian-born photographer Inge Morath in 1962, and the couple had two children, Rebecca and Daniel. He collaborated with Morath by writing the texts for three books. Miller’s own memoirs include Salesman in Beijing (1984) and his autobiography, Timebends (1987). The marriage lasted until Morath’s death in 2002.

In the 1990s, three new plays, The Ride Down Mount Morgan, The Last Yankee, and Broken Glass, brought renewed attention. Miller’s themes of success and failure continued to resonate and find a new audience for revivals of his earlier work, including a 1996 film of The Crucible, a 2005 Tony-winning production of Death of a Salesman, and, most recently, acclaimed reinterpretations of A View From The Bridge and The Crucible from director Ivo Van Hove.

Death and Legacy

By the time of his death at age 89, Miller’s work was being performed somewhere around the world on any given day of the year. Miller died of heart failure on February 10, 2005, which coincided with the 56th anniversary of Salesman's original Broadway opening, surrounded by family and friends. The BBC obituary praised Miller as “a man of the highest integrity, both in his work and in his personal life, Arthur Miller was an old-fashioned liberal, who never accepted the American dream at face value.” Besides his many plays, his legacy includes The Arthur Miller Foundation for Theater and Film Education, chaired by Rebecca Miller, which promotes access to theatre and film education for NYC public school students.