Merrily We Roll Along :

A conversation with Alan Gomberg, Stephen Sondheim Scholar

Posted on: March 13, 2019

On February 9, 2019, Alan Gomberg spoke about Merrily We Roll Along with education dramaturg Ted Sod as part of Roundabout Theatre Company’s lecture series. An edited transcript follow.

Ted Sod: How and when did you get interested in Sondheim’s work? What made you want to know everything you could possibly know about this particular artist?

Alan Gomberg: I was twelve when Company was produced, and I bought the cast recording, I listened to it hundreds of times, and I saw the show twice. At that age, you become very easily obsessed. A lot of people have become obsessed with Sondheim. It was Company that really established Sondheim as a major artist. Suddenly he was being interviewed and written about all over the place, so there was a lot for me to gobble up.

TS: Before that had you been aware of his work?

AG: I knew his name. I had the cast recordings of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum and Gypsy and the soundtrack of West Side Story. I think I’d seen the film versions of all three, and I think I had read the published scripts of Forum and West Side. And I knew he’d written the lyrics for Do I Hear a Waltz? But it wasn’t till Company that I had a sense of him as a particular force in the theatre. Soon after that I also got to know the show that at the time was most obscure, Anyone Can Whistle.

TS: Do you consider him a genius? I’ve heard him described that way and it makes sense to me because of the breadth of work and the sheer brilliance of his lyrics and music.

AG: He has said that the only genius he’s ever worked with was Jerome Robbins. I think his saying that has made me reluctant to use that word. He certainly is a genius compared to most of us.

TS: Can we talk about the musicals he collaborated on with Hal Prince? For those who are not familiar with the six shows of the Prince era, which were produced between 1970 to 1981, they were bookended by two shows with books by George Furth. Furth wrote the book for Company, which was the show that started the Sondheim-Prince collaboration, and he also wrote the book for Merrily We Roll Along. Can you tell us about why those musicals are so important to musical theatre history?

AG: Sondheim and Prince later reunited for Bounce, a revision of the show originally called Wise Guys. That later became Road Show. Bounce was produced in Chicago and D.C., but didn’t came to New York. Their 1970s collaborations were certainly groundbreaking. The critic Martin Gottfried referred to their shows as “concept musicals,” and that term caught on. The idea being that there was a central concept unifying the writing and all the elements of the production. Sondheim and Prince themselves didn’t really use the term to describe their shows, and Sondheim doesn’t like the term. Sondheim has said that one of his basic principles is that content determines form. Hal Prince learned from Jerome Robbins that when you’re doing a musical, which is such a collaborative art form, it’s important to talk. The people writing it and designing it and even orchestrating it need to talk frequently so they all are collaborating on the same show. Often musicals have failed because when they open out-of-town and they’re talking about what they need to fix, they realize that the librettist thinks the show is about one thing, the composer thinks the show is about something else, and the director thinks the show is about a third thing. So really knowing what the show is about, not just in terms of plot and character but thematically, was very important to the creation of the Sondheim and Prince shows.

TS: When I interviewed the late Joe Masteroff and John Kander about our revival of the revival of Cabaret, it was fascinating that they both mentioned that they too didn’t understand this term “concept musical” because it was applied to Cabaret too.

AG: Yes, it was, although I think it wasn’t applied to Cabaret until several years after it was produced. Concept musicals, if we consider the term a valid and useful one, were not invented in the 1960s or ‘70s but went back at least as far as the 1940s, with shows like Love Life and Allegro.

TS: It’s been said that the idea to musicalize Merrily We Roll Along came from Judy, Hal Prince’s wife. Is there truth to the fact that Judy Prince encouraged her husband to direct a piece about teenagers?

AG: The story he has told is that Judy said something like, “We’ve got two teenage kids” – Daisy, who ended up being in the original production of Merrily We Roll Along, and Charley, as in Charley Kringas, who is now a conductor. “They’re both smart, and they have a lot of feelings about the adult world and what’s wrong with it. Why don’t you do a musical about young people and their feelings about the adult world?”

And then one day as he was shaving, Prince remembered the George Kaufman and Moss Hart play Merrily We Roll Along, which he had not seen, but he had read and had great affection for. He thought, “I want to do that as a musical. I think it would make sense to cast that with young people.” It had not been cast with young people in 1934 when the play was produced. He then called Sondheim, who he says is always the devil’s advocate when he proposes a new project, and he said, “I want to do a musical of Merrily We Roll Along with young people,” and for the first time ever in Hal Prince’s experience, Sondheim said right away, “Yes, I will do that. I am with you!”

TS: Did they immediately go to George Furth to write the book?

AG: I was surprised to find while looking back at old articles that the first announcement of the show in The New York Times in April 1980 did not mention George Furth but I’m sure he was already involved. By late October 1980, there was a full draft of the book with most of the songs, so he had to have been involved by April. Maybe the Times didn’t think that Furth was as worthy of mention as Sondheim and Prince.

TS: What’s fascinating about Merrily is that, like the reverse chronology of the piece, that is also in the Kaufman and Hart play, these artists continued working on this musical for a very long time.

AG: Sondheim and Furth did, but Hal Prince, feeling that he had failed in the original production, did not. He came to feel that it was a mistake to cast it with young people, and he felt that he had not come up with a visual concept that worked. He’s a very visual director. He had been afraid to go with the visual concept that he wanted to go with, which was minimal scenery, sort of like Our Town, but with racks of costumes on stage from which the cast would pull. He was afraid that audiences might feel they should be getting more for what they were spending on tickets. So he felt that the set didn’t work because he hadn’t gone with his instinct on it, and as a result the production didn’t work. By the way, Fiasco has done something like Prince’s idea about the racks of costumes.

TS: You saw the original production quite a few times – correct?

AG: I saw that first production six times. And I second-acted it twice, too.

TS: Lonny Price, who was the original Charley, has made a stunning documentary about the original production that I found to be heartbreaking. It reflects on why the show failed and what has happened to some of the young people cast in it over the years.

AG: Yes, Best Worst Thing That Ever Could Have Happened. It’s a beautiful film.

TS: How did the original production affect you? What changes did you see happening?

AG: The first time I saw it was the third preview. I hate to say it, but it really was a shambles at that time. I had read the play Merrily We Roll Along, so I could follow it more or less, but I could tell that people in the audience were having a lot of trouble, and I could understand why. At that time, the musical was closer to the Kaufman and Hart play in some ways. Of course, the play takes place much earlier in the 20th century. It starts in 1934 and ends in 1916. For the musical, they updated it to their own times, and the character names and certain basic facts about them are different. In the play, the protagonist, Richard Niles, who becomes Frank in the musical, is a playwright. The Charley Kringas character in the play, whose name is Jonathan Crale, is a painter. He does a painting of Richard and his wife, Althea Royce, a famous Broadway star, in which Frank has one arm around Althea and the other arm around a cash register. And that painting is what destroys the friendship. In early previews of the musical, they were following the Kaufman and Hart play more closely in having a lot of recurring characters whose stories we followed to some degree. They were subordinate to the six main characters, but there was a lot to try to follow, and it was confusing. Prince and the writers decided to not make cuts during rehearsals. They probably should have made some cuts before they started previews. And the concept for the production was not helping. The cast was not as young as they’d originally intended, many of them were in their twenties, but they came off as quite young and raw, which was what Prince wanted but it didn’t work for audiences. Perhaps some of them were not ready for Broadway. I would say that the original actor cast as Frank was not ready for that role. He seemed tense and nervous when I saw him. He was replaced a week-and-a-half later by Jim Walton, who had been playing Jerome, Frank’s lawyer.

TS: They also got rid of Ron Field, the choreographer.

AG: Ron Field was used to working with top-notch Broadway dancers, and with one or two exceptions, the cast did not have top-notch Broadway dancers. Most of the kids didn’t even really move well, or so he complained. Larry Fuller, who had worked with Prince on Evita, Sweeney Todd and On the Twentieth Century, took over, and he made major improvements.

TS: A lot of people seem to attribute the failure of the first production to hubris among the creators because they didn’t go out-of-town to try it out.

AG: Prince has said it was a mistake to not go out-of-town. They thought they would save money. For some time fewer musicals had been going out-of-town. They hadn’t gone out-of-town on Sweeney Todd and that worked out very well. For Evita in London, they did only eight or nine previews before they opened. But Merrily was a very different matter. I don’t think it was hubris, but it may have been a mistake.

TS: For those who are keeping track of the original cast, a number of them have gone on to really wonderful careers.

AG: That is one of the things that I think is sometimes forgotten. At the time, the critics were overall fairly kind to the cast, but I spoke to some people who thought that the cast was untalented and that none of them would do anything again. Many of them did leave the business, but a number of them have continued to work, some of them very successfully. Tonya Pinkins, Lonny Price, Jim Walton, Jason Alexander, Giancarlo Esposito, Liz Callaway, Donna Marie Elio (now Donna Marie Asbury). Ann Morrison left New York but she worked regionally.

TS: In seeing subsequent performances after the early previews, did you see much improvement?

AG: I was at the third preview, and the last time I saw it was the closing performance. There were massive improvements, although there was one thing that puzzled me. When I first saw it, there was a moment in the second scene when Gussie goes to push Meg, the young actress with whom Frank is having an affair, into a swimming pool. The swimming pool was represented by a rectangular structure on the stage floor, and there was a piece of blue paper representing the water stretched across it. Gussie goes to push Meg in, but Gussie falls into the pool instead. She literally fell through this piece of blue paper, with the stage floor open beneath it. You could hear the tear. When I saw the show again, a week-and-a-half later, so many changes and improvements had been made -- including Jim Walton having taken over as Frank – but the swimming pool was still there! But it was eventually gone.

TS: There were 44 previews and 16 performances. Can you tell the audience what happened after that first production?

AG: The version that opened on Broadway was licensed and made available for production. It wasn’t exactly what had opened on Broadway, there were a few changes. Some monologues that helped to introduce the five principal characters around Frank were cut, and the first-act version of “Not A Day Goes By” was given back to Beth. Sally Klein, the original Beth, had sung it for the first three weeks or so of previews, and then it was given to Frank. Within five months of the Broadway closing, there were starting to be productions, mostly at colleges and community theatres all over the United States and also some in England. In 1983, a production with students of the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London got great reviews and a lot of attention. A few commercial producers, including Bill Kenwright and Cameron Mackintosh, expressed interest in moving it to a commercial run, but Sondheim and Furth were planning to revise the show and they wouldn’t allow that.

TS: Around this time, James Lapine directed it at La Jolla Playhouse. What changed? Did Lapine direct a completely rewritten version?

AG: That was in 1985. Some major rewrites had already been done, although more would come later. “Rich and Happy” was replaced by “That Frank,” which is mostly sung by Frank’s friends about him. Sondheim said the reason “Rich and Happy” was replaced was because when he wrote it, he did so with the idea that it was going to be performed by young people, so he wrote it from a young person’s idea of adult sophistication. He then thought that the song would make no sense if the show was being done with older actors, so he wrote “That Frank” to replace it. Many people prefer “Rich and Happy,” and it’s back in this production. Also, the song “Growing Up” was added for La Jolla, and there were a lot of changes to the book.

TS: There have been many revivals. Do you know which of those were fundamental to the evolution of this piece?

AG: The La Jolla production was the first in which Sondheim and Furth made major changes. One of the other important changes in the production was that they eliminated the opening and closing high-school scenes that were seen on Broadway. In the first scene of the Broadway version, 43-year-old Frank came back to his high school to give a commencement address. And in the final scene, we were again at the high school, seeing Frank at 18 giving the valedictorian speech, which is also in Kaufman and Hart. Those scenes included the song “The Hills of Tomorrow,” although we only heard it complete in the final scene. That was the song that Frank as a young composer wrote for his graduation class to sing. The removal of “Hills of Tomorrow” is somewhat odd because several other songs in the score are built upon it. Though it may not seem obvious the first time you listen to the score, all of the songs we hear that were composed by Frank are variations on “The Hills of Tomorrow,” as if Frank is continually reworking the melody until it reaches its most perfect form, or a less charitable interpretation would be that he really only has one song in him.

TS: Let’s talk about the other two seminal revivals.

AG: After La Jolla in ’85 there was a production in Seattle in ’88 in which Furth was involved and that seems to have had some further book changes. Meanwhile, small theatre companies were still being allowed to do the licensed version. Some of them removed older Frank, who had been added to the opening and closing scenes late during Broadway previews.

Then in 1990, it was staged at Arena Stage in Washington, D.C. This was the first production in which Gussie became a performer, and the first time that her second-act–opening version of “Good Thing Going” was in the show. In the Kaufman and Hart play, the Gussie character was an actress, but in the original version of the musical Gussie was a society dilettante who married a slightly crass but likable Broadway producer. There was also an attempt to employ a sort of framing device by starting with part of the 1957 rooftop scene, with Frank and Charley meeting Mary for the first time. Then the production went to the party scene in California, and from there it moved back in time, and at the end there was the complete rooftop scene. That was never done again.

Then in 1992 in Leicester, England, there was a production at the Haymarket Theatre, which received a cast recording. At that point they made the last major change, which was to take what had been two scenes and make them into one scene. Those were the scenes at the Beverly Hills Polo Lounge, where Mary sang “Like It Was, and Charley tries to make it up with Frank, and the scene on the talk show. In the version that is currently licensed, it’s all in a television studio, with some dialogue revisions. Today, we saw them again as two scenes, although Fiasco is using the name of the restaurant in Kaufman and Hart’s version of the scene -- Le Coq D’Or – rather than the Polo Lounge.

TS: It feels like the work never stopped. How present were Furth and Sondheim in this evolution?

AG: They were very present. And the work did stop eventually. The version done in New York in 1994 at the York Theatre Company is what is licensed now. There was also a cast recording of that production. Soon after that production, the old version could no longer be licensed. A couple of the later major productions had some adjustments, but that 1994 version is what is licensed. But there was one major production that was an exception. In 2000, there was a production at the Donmar Warehouse in London. That production caused some problems because Michael Grandage wanted to use some aspects of the 1981 version. Sondheim said in The Sondheim Review that Grandage was going to try putting back the graduation scenes. Later he said that he and Furth had no idea the production was going to do the original version, and they would have stopped it if they had known. And the truth is the Donmar production did a lot more than put back the graduation scenes. They did a real mix of the two versions, and I guess Sondheim and Furth didn’t know they were going to go that far. But the production was a success and got great reviews and won awards for best musical.

TS: We should mention that the Arena version you talked about was directed by Douglas Wager and choreographed by Marcia Milgrom Dodge and the 1994 York version was directed by Susan H. Schulman. Can you talk a bit about how Fiasco came up with the version we saw today?

AG: I know that they were given a number of drafts to look at. They’ve incorporated some lines that were performed during previews in ’81 and were cut before the opening, along with a few bits from the monologues that were in the opening-night version but not in the first licensed version. There’s also the use of the 1981 versions of the two scenes we discussed a few minutes ago. Probably the most surprising thing is that there’s a whole scene in this production that is not in any earlier version of the musical. That is the scene where Frank and Beth are living with Beth’s parents. It’s adapted from a scene in the Kaufman and Hart play. A fair amount of the scene here comes directly from the play but there is some new dialogue.

TS: It’s amazing what they had to do to create a revised version. They have to get the blessing of four estates and Sondheim gave them everything he had in his personal archives. I believe that this musical is personal for Sondheim because it talks about how difficult it is to have a relationship and a career simultaneously. Do you see this musical as a piece about losing faith?

AG: Certainly, that is not what was intended in 1981, and I don’t think that’s what Sondheim and Furth were going for in the revision. One of the odd things that happened in 1981 is that in the lead-up to the production, Prince said that the show was not going to be an especially serious evening. It was the first Sondheim-Prince show since Company that was called a “musical comedy” in ads and the playbill. Sondheim has talked about how he had been using extended and open song forms in most of his earlier shows, but in Merrily he wrote mostly 32-bar type songs, more like old-style musical comedy. Even though most of the songs are not exactly 32 bars, they tend to be more traditionally structured. They saw it as a show about hope and a positive show. Jonathan Tunick, the orchestrator of many of Sondheim’s shows, later talked about how they told him it was going to be fun and upbeat, but he was puzzled when he started to look at the material because it seemed to him that it was a very sad show. I think Prince’s perception of the show as more upbeat had to do with the casting of young people. A lot of people had trouble believing those kids as bitter middle-aged people. I never thought I was supposed to. I thought I was supposed to see the youthful hope in those people all the way through the show. I do think it’s a show about loss of hope and innocence, but in all the versions we end with young people believing they can change the world. We have a perspective they can’t have, so it’s bittersweet. It’s not just bitter, and it’s not just hopeful. It has both. That’s why it’s so moving.

Audience Question #1: What do you think the impact of Frank Rich’s New York Times review panning it had on the production?

AG: Well, he did praise some of the score. He didn’t praise all of it, but he wasn’t alone in that. His review certainly hurt the show greatly, and most of the daily papers and television reviews were not positive, and there had been so much bad word-of-mouth. But there were more good reviews than is sometimes realized. Clive Barnes -- who had been the critic for The New York Times for some years but was then writing for the Post — gave the show its most prominent favorable review. If he’d still been on the Times and had written that review, the show would surely have run at least somewhat longer. And there were good reviews from some others, including Michael Feingold in the Village Voice. Liz Smith tried to make up for having been among the first to spread bad word-of-mouth in print. A few days before it opened she wrote that she was hearing that the show had improved so much that it might be a hit. And it is true that audience response had improved greatly. I saw audiences so genuinely involved in it, huge amounts of laughter at points, and it seemed that many people were very moved by the end. I thought it was a terrific show by the time it opened.

Audience Question #2: Do you think the original cast album was one of the persistent forces in making it a more dominant work?

AG:Absolutely. RCA did not want to record it after the reviews came out. Hal Prince and Thomas Shepard, RCA’s producer of cast recordings, had to put pressure on them to do it, and Prince had clout. When the recording came out, some of the critics who had at first believed the score was below Sondheim’s usual standard changed their minds, saying things like “When you get away from the production and just hear the score, you realize it’s fantastic.” Within three or four weeks of its release, there was a Newsday article about how the recording was proving to be a surprise hit for RCA, selling as well as the RCA cast recordings of two current hits, Sophisticated Ladies and 42nd Street. So the cast album that RCA was sure they would lose money on sold extremely well from day one. People fell in love with the score and wanted to see the show. It certainly is one of the reasons why the original licensed version was performed all over the place by colleges, community theatres and even high schools, until it was supplanted by the revised version. That would not have happened without the cast recording.

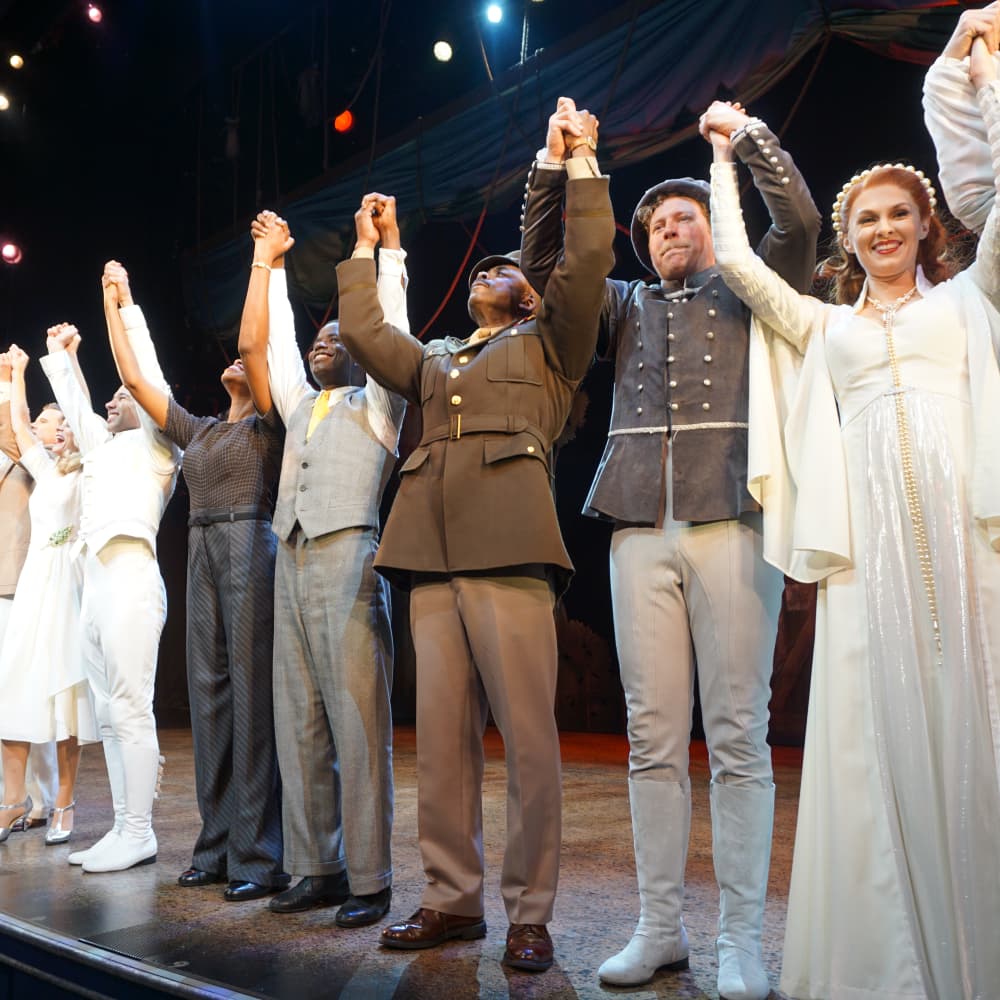

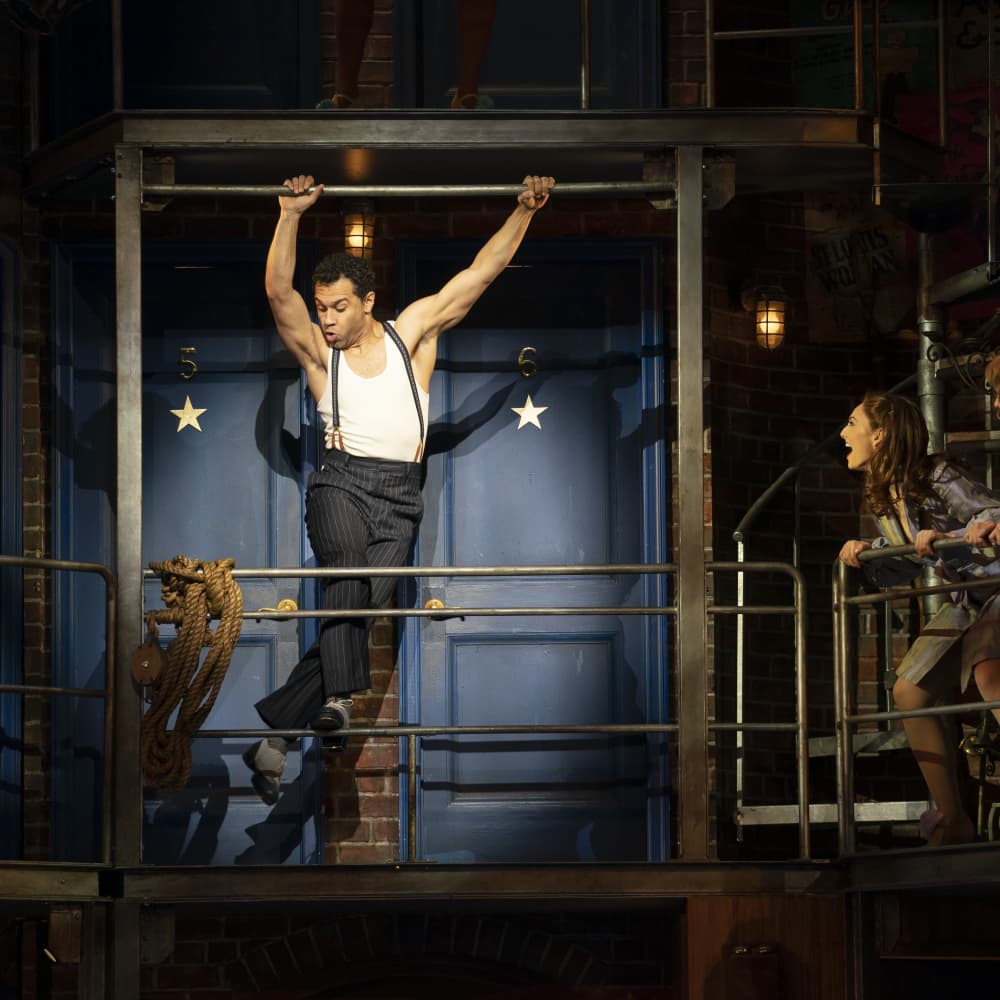

Merrily We Roll Along is now playing at the Laura Pels Theatre through April 7. For tickets, visit roundabouttheatre.org. For more information about our Lecture Series please click here.