Kiss Me, Kate:

Interview with Paul Gemignani

Posted on: June 3, 2019

Education Dramaturg Ted Sod spoke with Paul Gemignani about his work as Music Director for Kiss Me, Kate.

Ted Sod: Were you born in California? I read you were educated in San Francisco.

Paul Gemignani: I was born in Albany, California. It’s across the bridge and west of Oakland. It’s almost on the water. And I was educated at San Francisco State University because the music staff was incredible. On the faculty teaching you your instrument were Laszlo Varga, Earl Bernard Murray, and the entire San Francisco Symphony. Roland Kohloff taught me percussion. Several of us gave up scholarships to other colleges in the area because of the collective talent in that music department.

TS: Will you talk about the teachers or other professionals who had a profound impact on you?

PG: Jewel Lord was a high school music teacher who let me do everything. He let me conduct, he let me write, anything I wanted to do. I must have played four or five instruments in high school before I made up my mind. He didn’t care. He was a professional French horn player who taught school, and he was fantastic. The other influential teacher in high school was Arley Richardson, who was a woodwind player. They were both very open. They weren’t dictatorial. That’s totally unheard of in the music business. Lenny Bernstein, even though I never took lessons from him, taught me every day of my life. And Steve Sondheim, too. Those people have influenced my career the most.

TS: On Kiss Me, Kate you’re going to be music director and conductor. Can you tell us what those job titles are responsible for?

PG: The music director is responsible for teaching the score and teaching it in a way that will make both the composer and director happy. The conductor conducts the orchestra every night as part of the performance. On Broadway, they hire someone called a “contractor” and that person hires the band. I don’t like to do it that way. The guy who first hired me on Broadway didn’t do it that way, and I thought it was a great idea, because I can hire people who I know will make the orchestra sound the way I want it to, which is my responsibility. In Kiss Me, Kate’s orchestra, there are three new people out of a total of 16 who have never played at Studio 54 before. It’s similar to what a director does with a cast, only I am casting musicians.

TS: Larry Hochman is doing new orchestrations, correct?

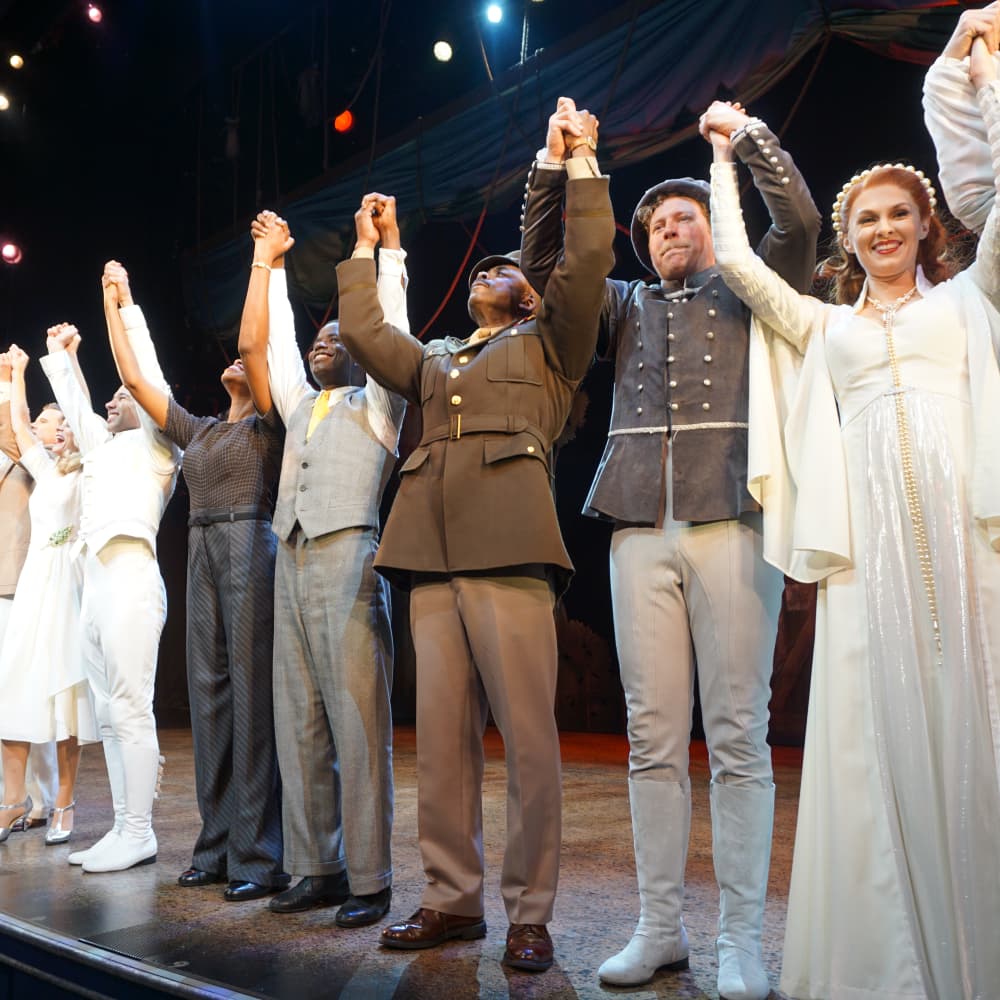

PG: Yes, because the revival I worked on in 1999, with Brian Stokes Mitchell and the late Marin Mazzie in the leading roles, was so specific. Don Sebesky was the orchestrator then, and we did a whole different thing on that.

TS: Is it a challenge returning to a piece you’ve already music directed?

PG: I erase everything; it’s like an Etch a Sketch. I think there’s a hundred different ways of doing something. The most important thing is to remember that you are working with different people who are gifted in different ways. Kelli O’Hara is not Marin Mazzie, and Will Chase is not Brian Stokes Mitchell, and vice versa. They don’t approach things the same way. I like starting with a clean slate. That’s part of the reason we’re doing new orchestrations.

TS: So, there are 16 in this orchestra. How many were in the ’99 version?

PG: I think there were four more. It’s not about Roundabout being cheap. I can get four more, but I can’t fit them into the stage left and right boxes at Studio 54—which is where the orchestra is situated. I love Studio 54’s set-up, because the orchestra can see the action instead of being underneath it.

TS: I’m curious how you decide which instruments will be in the house left boxes and which will be house right?

PG: Well, it’s funny you ask that. I’ve changed it. I need the strings by me this time around, because they need the most attention. That’s why I put them in front of me on the house left side. Why do I sit on house left? Because it’s a better view of the stage. I can see more if I sit there. In terms of which instruments go where, you think about families. The string family goes in one place, the rhythm family goes in another, the woodwind family goes in another, the brass goes in yet another. The rhythm section in a 1940s show always incorporates guitar, drums, and bass, so I put the rhythm section upstairs house left, above my head. I moved the keyboard player to the house right side, since he’s not playing rhythm. The woodwinds are sitting below, and up above that we have a bigger brass section than usual (two trumpets, a trombone, and a French horn). They are actually building a platform and fixing that area in order for this band to fit. We’ve had more people playing shows at Studio 54 before, but not this particular instrumentation. That’s why we have to change it.

TS: How different is it to music direct a revival like Kiss Me, Kate as opposed to a new show?

PG: With a new show, you don’t know what’s going to work. You know “So in Love” is going to work. You know “Too Darn Hot” is going to work. All you have to do is do a fantastic job of putting it together. At the first preview of Sweeney Todd, we had no clue. We did the first act of Sweeney Todd, and when I came back at intermission, half the audience had gone away. When we did the first preview of Sunday in the Park with George, we sang “Sunday” at the end of the first act, and when we came back after intermission, there was no audience there because they thought the show was over. With a revival, all you need to do is a superior job of putting this score together. You use everything you’ve learned about the score since that show’s original production.

TS: What are the challenges for performers singing a Cole Porter score like this one? Is there part of the show that you especially love?

PG: Well, I think “So in Love” is fantastic. I think all of Porter’s songs are extraordinary. The challenge in this score becomes working with somebody for whom the whole world portrayed on stage is different from what they know and understand. They need to explore the style of this music to the point where they can do it justice. Not for the audience, but for them, for their characters. To hold on to the beauty of the period and the Shakespearean language can be difficult for some people. It is sometimes a challenge for actors who were born long after the show was first written, because nobody hears music like that on a daily basis anymore. Which is, in my mind, all the more reason to do it.

TS: Why do you think Cole Porter’s work has staying power?

PG: I think he is a complete artist like Steve [Sondheim] is. I’m not comparing Porter to Sondheim, but he did write both music and lyrics. And when anybody writes both, their material is unmistakably intertwined. Kander and Ebb sounds like Kander and Ebb; it sounds like two people. With Cole Porter, the tune and lyrics come from the same soul and passion. I think Porter’s work has longevity because it wasn’t just frivolous. Yes, he’s funny and witty, but he also wrote a lot of poetry that has lasting power. If you read the lyrics to “Were Thine that Special Face,” you’ll understand what I am saying.

TS: You have been working with Warren Carlyle, the choreographer, and Scott Ellis, the director, for years now, and I’m wondering what you think makes this a successful collaboration?

PG: Scott and I have been working together since he was a performer in The Rink. Ever since he became a director, we’ve collaborated. We’ve done a lot of television together, we’ve done two productions of A Little Night Music at City Opera when it was going. He understands collaboration. I mean, when the choreographer can stand up and say to the director, “What would happen if we did it this way?” without getting his head bitten off or fired— that’s true collaboration. Warren and Scott take it one step further. Anyone sitting in that room can suggest things. It’s what makes their work great. It is why I’m here. It’s why I keep coming back.

TS: Scott says that you are absolutely the best at working with actors.

PG: The three of us care about each other and what we’re doing. Everyone working on a show of ours has a voice, which is what it’s always been about for me. That’s how I was trained by Hal Prince for 12 years in his office with Sondheim and other artists. I learned that collaboration means “speak up!” The ironic thing is that it doesn’t happen very often. I can count on my left hand the times Scott and Warren and I have disagreed, and we have, heatedly, but it is because we don’t want the audience to see a mediocre production. We want them to leave the theatre thrilled.

TS: You and your son Alex are going to be music directors on Roundabout’s two musicals this season. Kiss Me, Kate and Merrily We Roll Along will be running simultaneously. What did you teach him?

PG: He’s got many talents, and I always say to him, “You can do all these amazing creative things, and I can only do this one damn thing.” But, it’s true. Alex can do anything. He’s orchestrating Merrily, too. I taught him nothing. He learned by example. He was in the theatre with me a lot. I always answered the questions he asked about the theatre. When he was at Michigan and decided he wanted to be a performer and not a musician, I simply said, “Do what you want. Follow your heart.”

TS: Are there any musicals that you’d like to music direct or conduct that haven’t been revived lately?

PG: I would have liked to conduct Carousel. And funnily enough, I wouldn’t mind doing A Little Night Music again. Anything Steve Sondheim writes, I will do.