Bernhardt/Hamlet:

A Conversation with Theresa Rebeck

Posted on: October 22, 2018

On September 22, 2018, Theresa Rebeck spoke about Bernhardt/ Hamlet with education dramaturg Ted Sod as part of Roundabout Theatre Company’s lecture series.

Ted Sod: You were born in Ohio, you went to the Ursuline Academy, you graduated in 1976 or so, you did your undergraduate work at Notre Dame and you have three advanced degrees from Brandeis: an MA, an MFA and a PHD.

Theresa Rebeck: That’s all true.

TS: You are not only a playwright, but you are also a novelist, a writer for television— you created the series Smash—and you have two new movies coming out for which you wrote the screenplays—one with Bill Pullman and Anjelica Huston entitled Trouble and one with Jessica Chastain and some other fabulous women entitled 355.

TR: 355 is just in script form now. I wrote it for Jessica, Marion Cotillard, Penelope Cruz, Lupita Nyong’o, and Fan Bingbing, but that goes into production in the spring.

TS: You also directed the film with Angelica and Bill.

TR: Yes, I did.

TS: You are directing two plays, a revival of Crimes of the Heart, and a new play…

TR: By Rob Ackerman. I’m directing it this coming in the spring at the Working Theatre and it’s called Dropping Gumballs on Luke Wilson’s Head and it’s about a commercial—this is a true story—it’s about a commercial that the great documentarian Errol Morris made for AT&T in which the props person had to drop red gumballs onto Luke Wilson and chaos ensues. It’s a true story. It’s very funny, I think.

TS: And you have another play opening this season with Tyne Daly and her brother, Tim.

TR: Yes, Downstairs. I wrote it for Tyne and Tim and there’s a third character in it too, played by John Procaccino, who’s one of our great actors, and that’s going to be at Primary Stages. You should come see it; it’s quite remarkable. Tyne and Tim are remarkable together. You know, it’s the only thing they’ve ever done together on stage in their whole lives. It’s the first time they’ve been on stage together in fifty years.

TS: And when is that scheduled?

TR: It starts around November 8th and runs through Christmas, I think.

TS: Bernhardt/Hamlet is your fourth Broadway play, which makes you the most produced female contemporary playwright. Congratulations.

TR: Yes, it’s true. Thank you.

TS: That’s an accomplishment.

TR: Yes, it is an accomplishment. Obviously, there are other wonderful female theatre artists who have written musicals. But we’re basically talking straight plays. I don’t do musicals. I’d like to! In case anybody out there is looking for a book writer. It just hasn’t happened.

TS: Well, Smash was a musical of sorts.

TR: Yes, but it was on television and not of the theatre.

TS: Did I miss anything important? You live in Brooklyn with your husband and two children.

TR: Yes, that’s true.

TS: Anything else I should mention?

TR: I think that covers it.

TS: Great! So, in 2009, after we produced your play The Understudy, you were asked by Todd Haimes, our artistic director, to be a resident artist here.

TR: I think that’s when it was, yes.

TS: And with that you were given a commission, correct?

TR: No.

TS: No? Okay! Please explain how this play came to be commissioned.

TR: I had been thinking about this idea of writing a play about Sarah Bernhardt doing Hamlet. It’s something that occurred to me ten years ago and I thought it was a good idea and so I started reading about her. It was pretty clear to me that there was a play there, but I needed to think about it for a long time. I didn’t know how to start it. I didn’t know how to get into it. And then I said to Jill Rafson, “You know I’ve got this idea.” And she and Todd talked about it for a second and said, “Go do it.” Part of the reason I even approached Jill was because I thought, I need a hand at my back urging me to write this now. I was slightly avoiding it at a certain point, I didn’t know how to do it and I really did need someone saying, “Are you writing that play about Bernhardt yet?” And Jill provided that function for me.

TS: Jill Rafson has really been working on developing all the new work here at the Roundabout. Of course, Todd Haimes has the final say, but she has been fundamental to the success of the new plays we present.

TR: She’s exceptional. Can we all applaud Jill for a minute?

TS: What was your process on this? Did you lock yourself in a room? Did you go away from your home?

TR: I wish I had a steady answer. It’s changed a lot over the years. It’s better for me when I can lock myself in a room and just get myself through a first draft. With this play, I had the opportunity to go to the Sundance Playwrights Lab in Ucross. Philip Himberg, the artistic director there, called me and said, “Do you want to do this?” I had my little studio and I’d go there every day and I can actually get so much work done when I can clear everything out of my life like that. Once I had those three weeks at Ucross, I came out with about 40 pages. I will say I have an obsession with numbers and colors. I have that synesthesia thing – anyway, if I can get to page 62, then the play is almost done.

I had a draft of this play and Jill read it and I had friends read it to us and then Jill and I talked about it a little bit. It was very private. And then we did that again. Then we decided to do a reading for Todd and people at the Roundabout and make it more open to the community and that’s when we sent it to Janet McTeer and said, “Do you want to play Sarah?” Since then there’s been more readings and workshops and discussions. So that’s relatively a speedy process, if you don’t count the ten years when I was just looking at pictures of Sarah Bernhardt.

TS: I know you were also inspired by the poster work of Alphonse Mucha – who is a character in the play.

TR: I went to Prague with my husband and we did a tour of the Mucha Museum and every one of those glorious posters of Sarah Bernhardt is in the museum.

TS: So, for a long time you thought Sarah would be a good subject for a play. How did you land upon her wanting to play Hamlet?

TR: There are a lot of biographies about her, she had a very long, complicated, and fascinating life. She really is someone who reminded me of Joan of Arc in a peculiar way and I kept thinking, where did these women come from? How did Bernhardt create herself? Her mother was a courtesan and she never knew her father at all. She lies and makes up stories about it in things that she’s written. When she was about five years old, her mother, who was Jewish, left her at a convent and the nuns took care of her and she was becoming stabilized. I think she really liked it there. And then her mother came back a few years later and said, “I want my kid back.” There was nothing but chaos around her and she was not parented. And then she rose out of that. That’s very interesting to me. I felt like the moment she decided to take on Hamlet was the crystallization of her self-creation. She was 52 years old and at the height of her powers. It is a situation that presents a lot of fascinating gender questions that are occurring in wider and murkier ways now. She did this unthinkable thing, which was really moving to me. That’s really what I was interested in. I wasn’t interested in a biographical play, although obviously some biography is in the play -- like the fact that she slept in a coffin.

TS: Were you extremely familiar with Hamlet? How did you find the torturous things that actors go through when they play that role?

TR: I talked to actors who had played Hamlet.

TS: Well, there are amazing actors who have played that role. Did you talk to Benedict Cumberbatch?

TR: I did not. I don’t know him. I talked to Alan Rickman about it. He was really interesting.

TS: Was it just talking to the actors that helped you find your way inside taking on the role of Hamlet or did you read the play over and over? I feel that’s a palpable part of this play -- how an actor takes on a role and then has this self-doubt.

TR: One of the things that I found out fairly early on was that when she finally did the play, she did this version of it that had taken the iambic pentameter out. Janet and Moritz, the director, and I spent a lot of time talking about why that was. I never got to see that script she used. I looked all over for the one she ended up doing. Nobody knows where it is. You’d think they would, but they don’t. I was terrified of trying to make it up myself. Do you know what I mean? And then I thought, oh, I should have Rostand do it! Then I’d have somebody on stage really grappling with how terrifying the idea of rewriting Shakespeare might be. You know you’re in a good dramatic place when both sides of the argument are right. Because ultimately what she did was to restore the heart of the play. There are a lot of bastardized versions of Hamlet out there and they take a lot of the scenes out. She was right at the forefront of the beginnings of naturalism and she wanted to present something more emotionally truthful. She really wanted to perform a more naturalistic version of who Hamlet was, what he was feeling, what he was looking for. And to her, the iambic pentameter stood in front of that. I didn’t make that up. I did have to pick and choose which bits of Hamlet we were going to see in Act I, and then the play moves forward off that discussion.

TS: Being such a brilliant actor/manager, she may have known who her audience was.

TR: I don’t know.

TS: I want to talk about finding her relationship to Rostand. How did you find that and how did you decide that it had to have this dramatic impact when he couldn’t finish her requested prose version of Hamlet?

TR: They worked together on two plays before he wrote Cyrano. One is Princesse lointaine and then they did La Samaritaine. And then he wrote Cyrano and, if you read Cyrano, he’s clearly writing about her. Who she was. It is just factually true that when he was working on Cyrano, she was starting to work on Hamlet, so those two things overlapped. And, also, apparently to know Bernhardt was to sleep with her. People just fell in love with her and adored her. I just shoved things together. I wanted there to be a sturdy argument between two people who were deeply entwined in each other’s psychology, where there was real intimacy, where the argument of the play could be played out.

TS: You have two powerhouse scenes in Act Two back to back – first is the one with Rostand’s wife, Rosamund, asking Sarah to read Cyrano and requesting that Sarah allow Rostand to finish it, and then after Sarah reads the play, she confronts Rostand and she tells him quite bluntly that Roxanne is not a great part.

TR: Every woman I know is happy that I did that. All of us are out there thinking, I love Cyrano. Why is Roxanne such a drip?

TS: I’ve noticed watching the play that women sit up when that moment happens. And the applause seems to be led by women. And I think to myself, Theresa isn’t a polemicist, as you’ve said many times, but you must have a feminist perspective.

TR: This is my view on it. I am who I am and my agenda’s the truth. I wouldn’t say I’m not a feminist, but I’m not trying to write feminist plays. I was trying to write a really good play about Sarah Bernhardt. And I think I did. The agenda is always the truth and telling an authentic story about people—that is really what I’m after. We live in dark times around questions of gender and power and early in my career, people would write nasty things about me saying, “She’s a feminist,” and I would think, well, Jesus, David Mamet’s a misogynist. And I thought, this is so peculiar because back then I was young and trying things out and I thought, I don’t even know that I’m very good at being a feminist. Because I didn’t have a political agenda. I just knew the world that I saw and there was something strange to me that people weren’t telling that story, which for me was the simple truth. In one of my early plays, Spike Heels, which was my first play to be done in New York City, the woman says, “Hang on, hang on. This doesn’t actually work for me.” And that was seen as provocative, when, in fact, it was just the truth. Does that make sense?

TS: Absolutely.

TR: I really love it when Edmond comes in and says to Sarah, “You knew this was going to be considered provocative if you did this.” And I think, of course she knew that, but I also think, what was she supposed to do? It’s not like she’s trying to be a provocateur. She’s trying to get at something that’s powerful and part of an artistic journey.

TS: And if the label offends you, I didn’t mean it to.

TR: It doesn’t offend me, of course I’m a feminist, but…

TS: But that’s not what you were writing.

TR: I’m not writing agit-prop. I’ve had to say that so many times. And I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that either. There are all sorts of different reasons to write a play. Getting at the truth is mine.

TS: Well, I think you’ve done it. And I’m curious how it will affect people. What I sense is that people want to hear what you’re saying. Ten years ago, I read a statistic from the League of Producers that said 75% of theatre tickets are bought by women and I thought to myself, wait a minute, then why are all of the plays written by men and directed by men? That doesn’t make any sense.

TR: Yes, we’ve raised this question many, many times.

TS: It takes so long for people to get it. One of the things that I thought was remarkable is the fact that Sarah says to Rostand, “No woman should have to play the ingénue,” but, ultimately, she goes on to play it. I think you’ve put your finger on it. You’re stuck. You want a career and yet you have to please those people who are in power. And it’s a complicated issue. People compromise themselves all the time in the theatre and elsewhere for all kinds of reasons.

TR: I would say, the play is the play and Sarah’s life is Sarah’s life. What I’ve learned is that she did go back and play Roxanne because Coquelin came with her to do Hamlet on tour, so I think it was a deal that they made with each other. Which, of course, we all do. I think that she and Rostand loved each other. And when Sarah died, the last people that were with her were her son, Maurice, and Rostand’s wife, Rosamund. There’s no question that these people remained entwined in each other’s lives. And Rostand wrote L'Aiglon for Sarah. That’s historically accurate. He wrote a britches part for her. I look at Rostand and I think he’s “woke.” When he says the things that he says to her in that last scene, it’s a way of throwing down the truth of what they are confronting together. And then I think he has to confront that he’s not as woke as he thought he was. And he does that. He writes his next play for her as a britches part and I think it’s a beautiful gesture.

TS: You write a lot about artists and artistic process. And in this play, there is this beautiful sense of community that really can happen on certain productions. That sense of community, is that something that you feel we’re missing in our lives? Because that’s what I feel the play is saying to me. It says, find your community, invest in your community and maybe you will be less depressed by what’s going on around you.

TR: I agree with that. A lot of times people say to me, “Why do you keep working in the theatre?” And I respond, “Well, because it’s beautiful.” That is one reason, but the other reason is because I think it creates community in this astonishing way, that we’re all here together, spending the afternoon together, sharing a story together and sometimes I can see something sparkly in the air when things are going well and that’s very moving to me. So, yes, I agree with you, Ted.

There’s this really beautiful book that’s one of my lodestones called The Gift by Lewis Hyde, and it talks about gift-giving cultures and how gifts create community in this anthropological way and he ties it into art as a gift of culture. And if you look at artists like Janet McTeer, you would have to say, “She’s gifted.” That a gift has come to her and when it moves through her, it moves back out into the community and that creates circular motion. That is what the purpose of art is. I’m not doing this book justice, but it’s quite powerful and argues for what you just proposed.

TS: Well, that’s what I took away from it because I feel like if you don’t wrestle with the themes of a play, what’s the point of seeing it?

TR: Yes, and I would also like to say I’m not a nihilist. I’m clearly not. There’s a lot of nihilism that’s out there in art and things get very, very dark and meaningless and that’s not what I’m going for. That’s just not where I live. And I think that’s what you’re sensing -- that this is a life-affirming enterprise.

Audience Question #1: Clearly, the part fit Janet McTeer like a glove. Did you have her in mind at some point when you were writing it or was it just a perfectly wonderful happenstance that she was available?

TR: I did not have a specific actor in mind for any of the parts when I wrote this. Sometimes I do, like when I wrote the play for Tyne and Tim Daly. But certainly when we got to casting a reading and they asked me and Moritz, “Who do you want to offer it to?,” and Janet’s name was on the list -- the two of us looked at each other and said, “Let’s just see if she’ll do it.”

Audience Question #2: First of all, thank you so much. It was a wonderful experience. I’m so happy to have a playwright in front of me because I’ve always wanted to ask this: Do writers think about us? I knew nothing about Sarah Bernhardt. Now, I want to go read about her, because it was so interesting and the play was so good. But do you writers think, how much information should I put in so they understand what’s going on and how much should I leave out? How do you make those decisions?

TR: I’m going to be honest, everybody’s different, obviously. I hate exposition. I’m one of those people who says, “They can catch up. They’ll catch up.” Because the thing about exposition is you have to have a very real reason for one person to tell another person a piece of exposition. And a lot of times, plays just grind to a halt when someone just starts telling. In 19th-century plays, they used to call them the “dust maid scene.” Have you ever heard of this? It was usually at the beginning of a light comedy and a couple of dust maids were literally walking around dusting furniture and saying, “When are they coming back?” “Well they’re coming back this afternoon.” “Did you hear that so and so…” and they baldly set you up -- who’s sleeping with whom and whose heart is broken and blah blah blah -- and then the play starts. And yes, we all laugh at that because it’s kind of stupid, and it is kind of stupid. For me, you have to have a real reason to put a piece of exposition in because the scenes die. I tend to be light on exposition and then people say to me, “Theresa, you’ve got to add a little more there. Figure out a way.” Of course, you want the audience to not be mystified by what’s going on. At the same time, there’s a lot of stuff about Sarah Bernhardt that I left out of this play because this isn’t a play about Sarah Bernhardt’s life, it’s about this moment in her life.

TS: Am I mistaken, or is television writing a lot of exposition?

TR: I think bad TV writing can often be a lot of exposition. Right? I do. I mean there are TV shows that I love. I love that show Better Call Saul; I used to really love Breaking Bad. That show slows down time a lot, but it doesn’t lean on exposition. But you’re 100% right. I’ve written my share of exposition for TV and I’m not doing that anymore.

Audience Question #3: I think one of the most satisfying parts of this show was watching these artists discuss their art as it was happening. I thought, how can I capture conversations that I’ve had in rehearsal rooms with people? I’m wondering if you have any advice?

TR: I feel like that’s a question of your ear. You can keep people talking for a long time as long as there’s forward motion in the speech and a good ear for dialogue. I’d go back and look at Shaw. Sometimes I get so bored reading Shaw, but he really knows how to set up an argument, send it flying and keep it going. With a lot of my arguments, I have to say to actors, “Yes, there’s 7,000 digressions, but you can never lose sight of the fact of where you’re going.” You really always have to have a major throughline and a passionate need to have this speech or this discussion so that there’s dramatic truth underneath. Shakespeare did it too. You have to really hang on to the muscle of dramatic truth. That’s partly what Sarah struggles with in this play -- the fact that Hamlet is so cerebral -- his brain can go there, but it gets detached from his gut.

Audience Question #4: Thank you for showing the video of Bernhardt at the end because during intermission, I googled Sarah Bernhardt audio and I was surprised because her voice was almost “trilly,” that’s the only word I can use to describe it. And I was wondering if, as you were writing this, you had the sound of her voice in your ear?

TR: I did not. I never listened to her.

TS: I will say that I’ve been reading about Sarah and I’ve read that her voice was supposedly absolutely mesmerizing.

TR: Yes, that’s one of the things I’ve read too.

TS: And her diction was said to be perfect, so I believe she knew how to play her instrument.

Audience Question #5: I feel a little guilty because it’s not so much a question as to thank you because I think this play is genius.

TR: Oh, thanks.

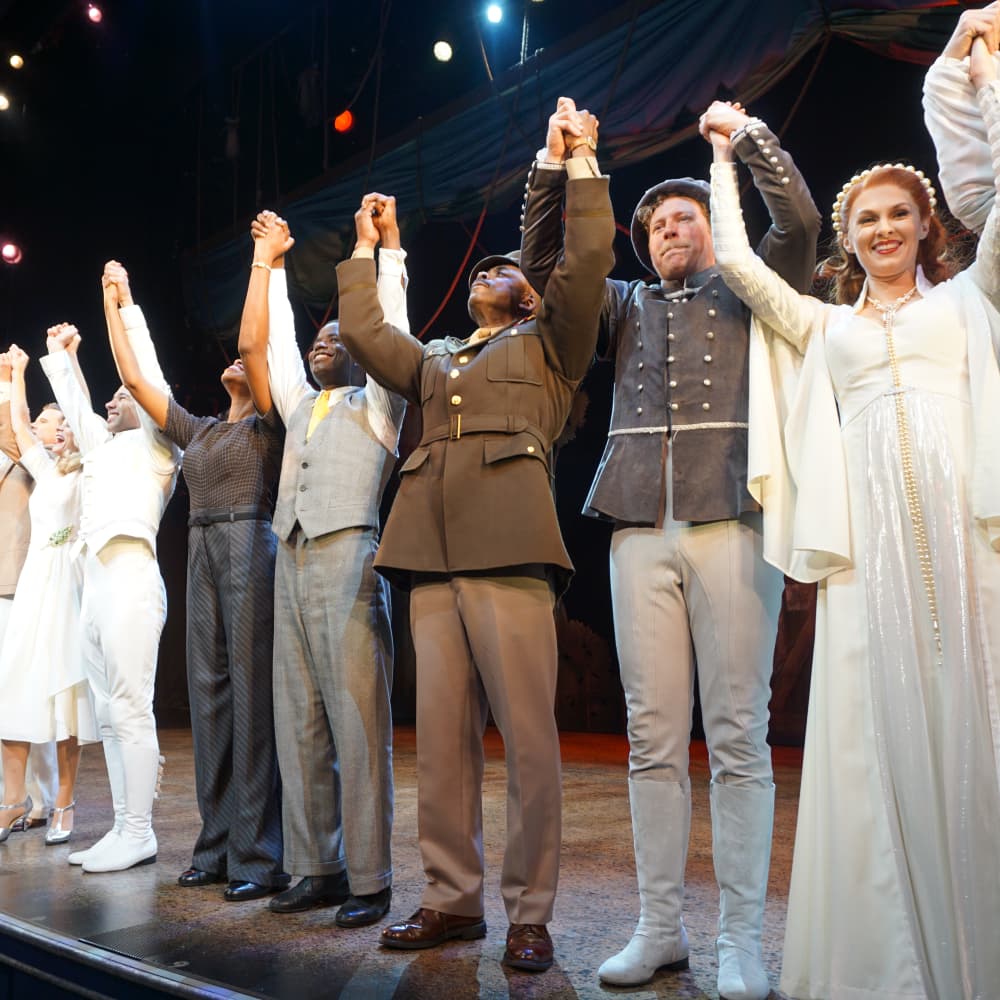

Audience 5: It kept blooming for me throughout the whole afternoon. This is going to be done over and over and people are going to get so much out of it and there’s going to be such richness in reading it. It was extraordinary. It was the most incredible ensemble. In the beginning, I worried a bit. I thought, is this going to be a problem play where it has to have Janet McTeer? And as it went on, I thought, no, there’s going to be a lot of talented people who can inhabit this because the words are so gorgeous. So, thank you.

TR: Well, thank you.

Audience Question #6: When we look back at the body of work of some playwrights, we see connections among their plays thematically -- subjects that they return to. Do you feel that way about your own work?

TR: I would have to say that I do feel that gender and power is a theme that appears and reappears. It’s just in my instrument. The other thing that’s in my instrument is a strong belief in a good laugh. I don’t understand why people don’t take comedy as seriously as I do. I’m always thinking, I’m sorry, but comedy was invented at the dawn of time alongside tragedy. And quite frankly, comedy is harder to do. And so, when people aren’t laughing I’m thinking, What am I doing wrong? -- which is not necessarily the most mature response. Sometimes you just don’t write a funny play, but I often do write what I think of as comedy.

TS: You return to writing about artists quite a bit.

TR: Yes, I do.

TS: And that’s important because you live in that world, I would imagine. And there are all different types of artists.

TR: Sometimes people say to me, “Where do you get your ideas?” And I say, “Well, I shop at the idea store!” Nobody knows where their ideas come from. I do have a sort of sturdy belief in the muse. I understand why the Greeks would invoke the muse, because ideas just show up and then you think about them for a while. It is a little bit like having somebody tap you on the shoulder saying, “This would be a good idea. What about this idea?” And I think that that’s partially because there’s always a lot of people talking to each other inside my head and that’s why I’m a playwright. I don’t actually feel fully in control of this and it’s just gotten worse as time’s gone on. Because now, sometimes people will ask me to do things and I think, Well, that sounds really interesting! And then this person inside me who I now call “Writer Girl” is thinking, Nah, I’m not doing that. And so sometimes, my agent or my manager will call and say, “Hey, could you…” and I’m responding, “Hmm, I don’t think she’s going to be interested in that.” They think I’m insane. I’m really not. I’m sort of like the agent of Writer Girl and I do think that Writer Girl is compelled by stories of gender and power. I feel like the world we live in is just marked by it. It’s just everywhere. I can’t get away from it. I don’t think any of us can.

Audience Question #7: I just wanted to thank you and Writer Girl. Having written a couple biographical plays, I know it’s a very difficult task. A lot of research is done. I was curious if Bernhardt performed in French?

TR: She did, yes.

Audience #7: So, the Shakespeare would have been translated?

TR: Yes, there were questions about that fact that I pondered a lot. And then I thought, I can’t. It got too convoluted. This was the cleanest way through it for me. I actually did go to the Folger Library because they have a copy of the Hamlet that she did when she was playing Ophelia. There were standard translations that preserved the iambic pentameter. So, this thing that she was doing in terms of taking the iambic pentameter out is historically accurate. But, yes, she performed it in French.

Audience #7: What is your take on Bernhardt versus Duse as the greatest actresses of their day?

TR: Sarah kicked Duse’s ass.

TS: And on that note…

TR: I don’t know very much about Duse. That was a slightly cocky response. There were some other things in the play about Duse that we ended up taking out, but they did the same thing that we do -- they would trash talk each other.

TS: Maybe that’s a TV series, Bernhardt and Duse Talking Trash…

TR: Ha, what a good idea.

TS: Can we please thank Theresa for joining us today!