True West:

Tinseltown Transformations: Hollywood in the 1970s

Posted on: February 5, 2019

Set in the late 1970s, True West follows its main characters’ competing journeys to sell a screenplay to a major Hollywood producer. Some of the biggest turning points in Hollywood history took place during this time period; as studio executives’ priorities changed, so did the types of films considered “hits.” An exploration of the shifting focus of the film industry during this time can illuminate the obstacles that characters Austin and Lee encounter in their quests to write and sell a screenplay.

The New Hollywood

The late 1950s and early 1960s are generally considered a low point in American cinema. With some exceptions, films of this time followed predictable and widely-used formulas. Many were war movies or Westerns featuring recycled plots and stars, and all were under threat of censorship by the Hollywood Production Code, which at that time set strict limits on the content allowed in motion pictures. What resulted was a decade of movies — including such big-budget behemoths as Cleopatra and Mutiny on the Bounty — that, in hindsight, are generally considered stilted and uninspired.

But the release of Bonnie and Clyde in 1967 ushered in an era that would later be dubbed “The New Hollywood.” Bonnie and Clyde, alongside a handful of other 1967 films, flouted traditional moviemaking practices, experimenting with plot structure, camera work, and subject matter. Drawing inspiration from the films of the “French New Wave,” a period of boundary-pushing French cinema that had begun in the 1950s, the works of “The New Hollywood” embodied the transgressive counterculture of 1960s America. Out of this era of American filmmaking emerged such young directors as Francis Ford Coppola (The Godfather), Mike Nichols (The Graduate), and Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver), whose films explored the taboo and embraced the uncomfortable.

The New New Hollywood

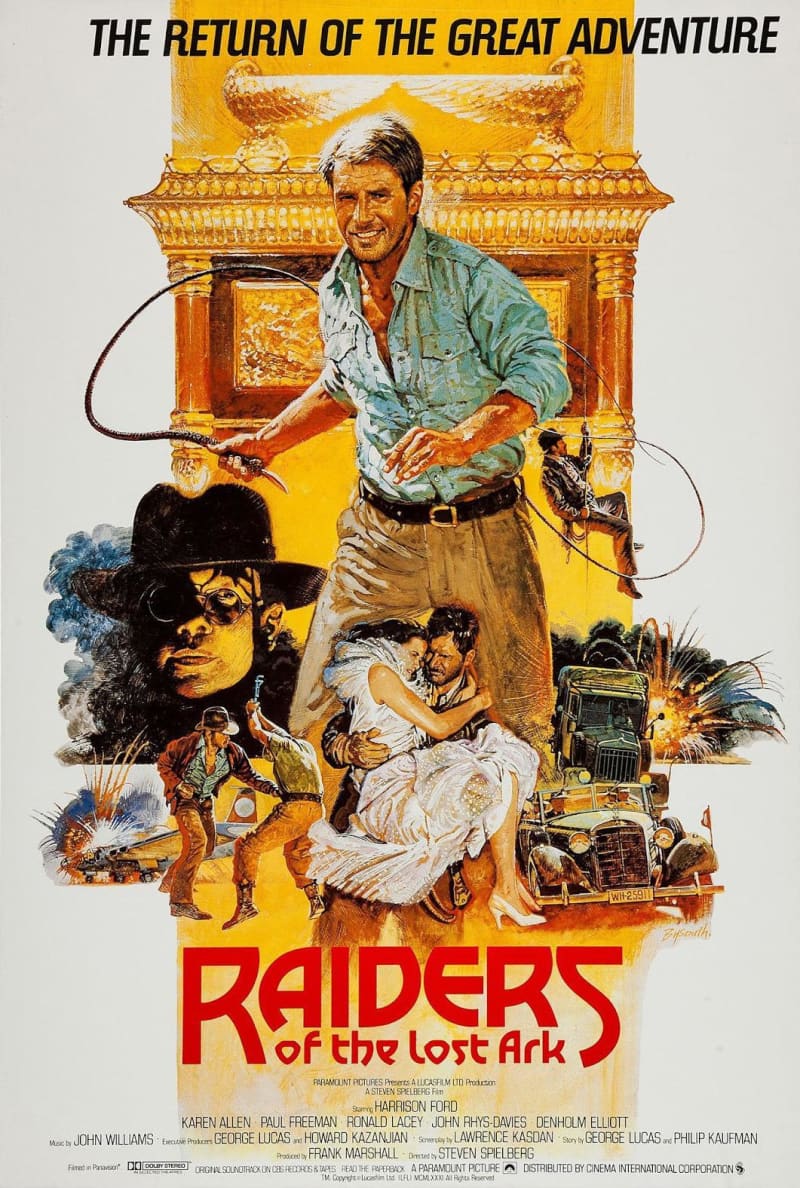

The era of “The New Hollywood” all but ended in 1975 with Jaws, a summer release that shattered box office records and introduced America to a new kind of film: the blockbuster. (The term “blockbuster” was originally used in World War II to describe massive bombs that could level entire blocks.) Blockbusters like Jaws, Star Wars (1977), and Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) changed the DNA of Hollywood, as the promise of never-before-seen profits sent film executives scrambling to produce the next megahit. Spawning action figures, theme park rides, McDonald’s Happy Meal toys, video games, and more, films like these became brands unto themselves.

Many lament the rise of this “New New Hollywood,” claiming that the obsession with blockbuster profits has resulted in decades of films made for money rather than for art. In 1980, The New Yorker published an exposé on the film industry titled “Why Are Movies So Bad?, or, the Numbers” by film critic Pauline Kael. In it, Kael—who had spent months studying the inner workings of Hollywood—describes an industry run not by artistic producers but by advertising executives, who had the final say in which films to produce based on which stars were interested in them and how profitable they were predicted to be. "To this day, blockbusters (and, increasingly, blockbuster franchises) create massive profits for Hollywood studios. Though Hollywood’s investment in blockbusters only seems to be growing, the cash generated by these films allows studios to fund their less-lucrative projects.

As True West takes place during the rise of the “New New Hollywood,” characters Austin and Lee unwittingly find themselves playing out this larger debate over the integrity of filmmaking: can the artistic and the commercial ever be one in the same? In approaching this question, it is important to remember that what constitutes a “good” film is always subjective. It would be an oversimplification to say that the most financially successful movies are always the “worst” ones—a box office success is, after all, a film that many people want to see. “Quality,” as True West explores, means something different to everybody.