True West:

Present in the Past: Stairway to Heaven

Posted on: April 3, 2019

Columbia@Roundabout is a collaboration between Columbia University School of the Arts and Roundabout Theatre Company which provides exceptional educational and vocational opportunities for the next generation of playwrights and theatre practitioners. The program includes an annual reading series for Columbia MFA students, Teaching Artist training facilitated by Education at Roundabout and two fellowship positions in Roundabout’s Archives. As a part of the Archives fellowship, the MFA candidates conduct deep research into our historic records and are encouraged to produce scholarship that explores Roundabout’s contribution to American theatre. James Monaghan is one of the first Archives Fellows. Over the course of the coming months, James will write a series of articles about Roundabout’s production canon.

True West can be a tricky show from a prop perspective- all the destruction of property that must be repaired every night and all those toasters. Sitting in the audience as Austin puts bread in each and every one of them you may rightly wonder, is there a point beyond the comic absurdity created by a leaning tower of toast? There are, of course, character motivations: Lee questions Austin’s street-smarts by telling him he couldn’t even steal a toaster, and Austin answers this challenge by stealing a dozen, thus–he feels—proving his prowess. The fact that a toaster is the object in question may seem incidental at first, but as you watch, the sheer number of them and Austin’s determination to product test each one may begin to make you think that the toasters are also playing another part, a part which a different object couldn’t play. Any other object could function just as well as a pawn in a brotherly squabble. Shoes, for example, seem just as insignificant as toasters; something harder to steal like jewelry might have resale value. But insignificance and resale value aren’t what the play wants us focused on in that moment. In this suburban setting, the mass of toasters starts to look like a symbol of rampant consumerism: an essential part of a balanced breakfast according to all the best marketing strategies, the promised cure finally arrived. Streamlined and gleaming they are (literally) a product of the American Dream and highlight the false security of domesticity that playwright Sam Shepard is interested in getting his audiences to consider more deeply.

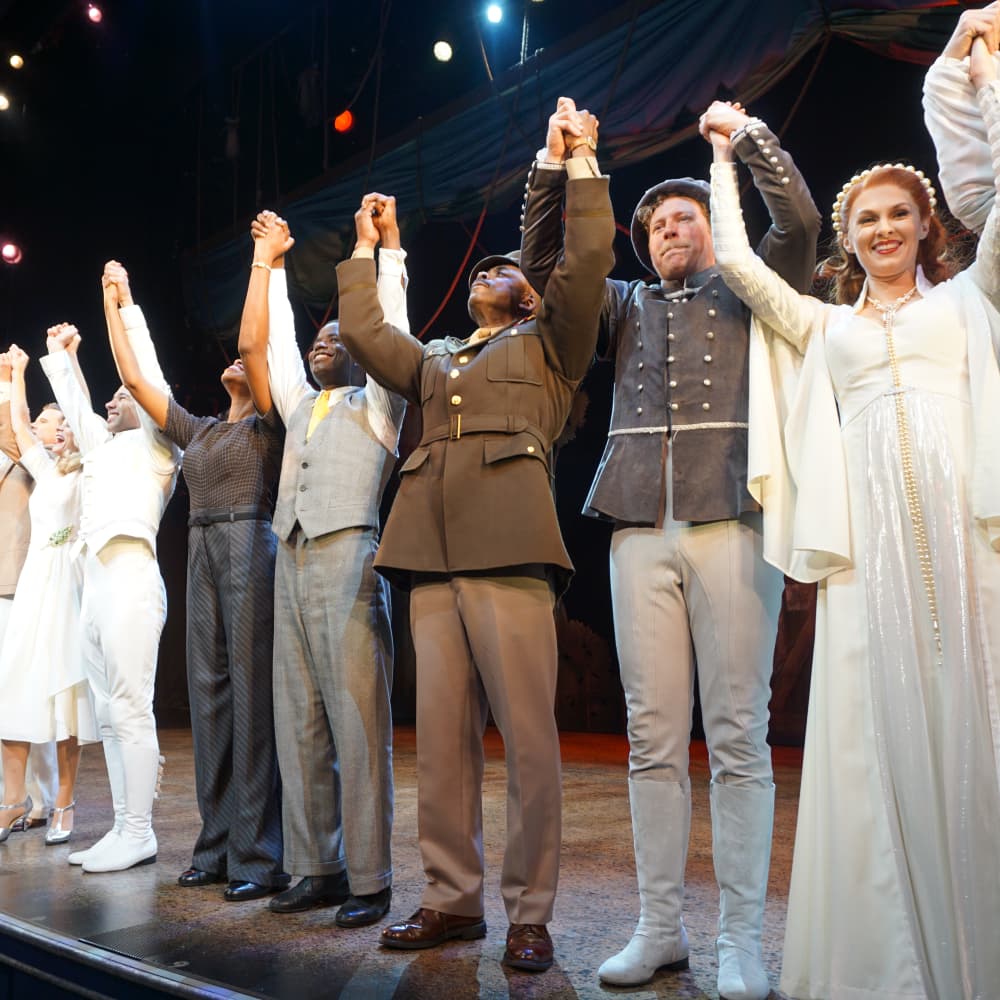

It is possible to think in this way about any manner of objects on stage, how their specific qualities, placement, and use layer meaning on top of their practical function – even something as essentially pragmatic as stairs. Roundabout’s 2003-04 production of Assassins is a veritable Escher landscape. Stairs travel all along the front of the stage leading out into the audience, there are stairs on left and right that lead to multi-level landings, and perhaps most prominently, a curved staircase with thick wooden beams winds its way down from unseen heights before planting itself in the seedy, carnival underworld. The support beams of this massive staircase provide most of the framework for the show, but the curved stairs themselves are utilized only once. During “The Ballad of Guiteau” assassin-in-denial Charles Guiteau ascends the steps like a man stepping onto the gallows, alternating between manic energy and righteous conviction. But as soon as he passes the devilish Proprietor and steps onto the curved staircase, its higher purpose is crystal clear – Guiteau has finally found the path to salvation and redemption. With no need for sign posts or flashing bulbs to communicate this to the audience, the scale of the stairs, the fact that they don’t seem to have an upper limit, their exclusive use by a character so fixated on his afterlife, gives these stairs, more than any of the others present on stage, significance greater than a mere path to an exit. The dramatic reveal of Guiteau’s body swinging from a noose at the song’s conclusion transforms the stairs back into their more literal role as the gallows steps.

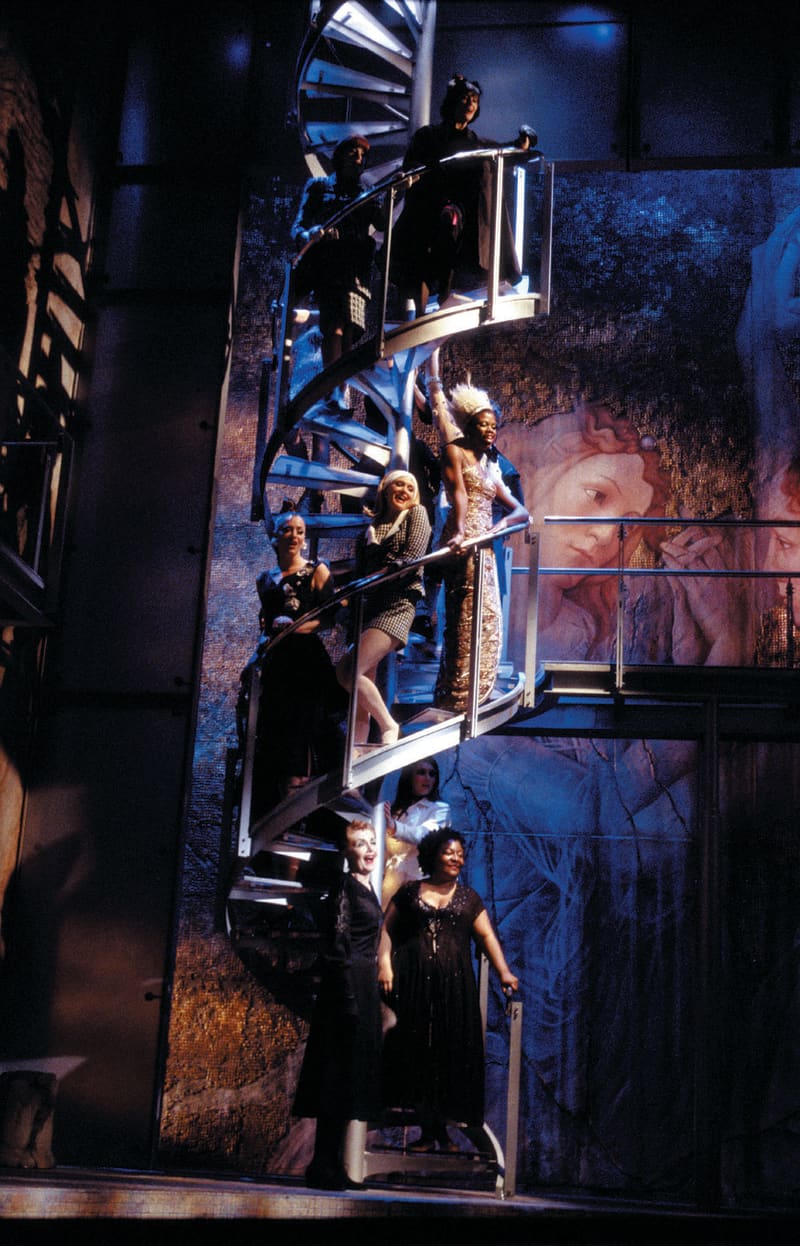

In another show from Roundabout's past, the 2003 production of Nine also incorporated a very particular set of stairs. These spiral and slink seductively from floor skyward. Like their wooden counterpart in Assassins, these stairs also end—or not—at an unseen destination. If all stairs are created equal, we might assume these also terminate in an afterlife, but the part this staircase has been cast in is quite different. Like the action of the play, this staircase folds in on itself, revisiting its own twists and turns. This staircase provides inspiration—delivering Guido, the protagonist filmmaker desperately in need of an idea, his muses one after the other. This set of stairs is an observation deck, a vantage point from which to reflect on memories. Architecturally, a spiral staircase usually takes up less space than a traditional one, but what it saves in space it spends in time. When Louisa, wife of the philandering Guido, has finally made up her mind to leave, it takes an exquisitely long time for her to do so, the turn of the staircase allowing her to maintain the eye contact connection that is breaking Guido’s heart with every step. In these ways, the staircase comes to be a kind of visual metaphor, exposing the DNA of the musical.

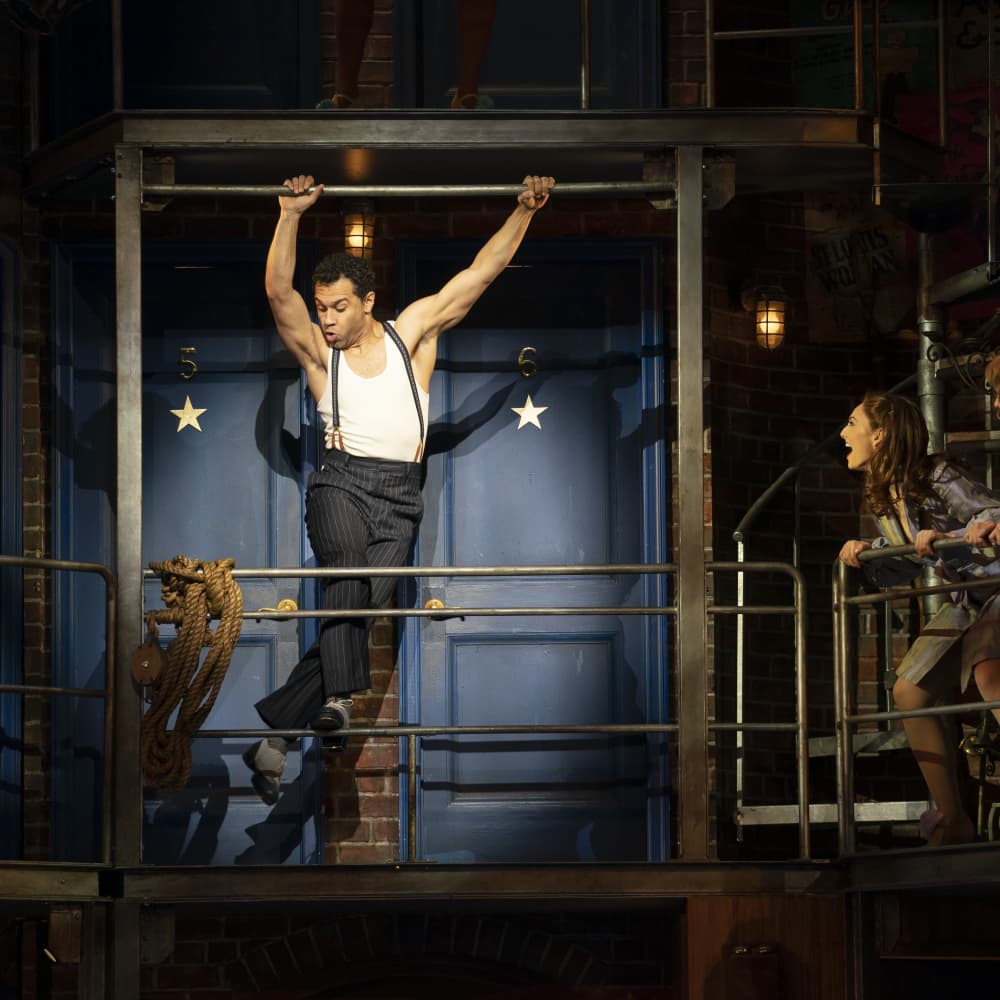

In Nine and Assassins, the stairs are arguably the most prominent element of the set. This makes sense given the limbo quality of the works where characters feel trapped between two worlds. But if you expand the search to include the staircase in RTC’s 2016 She Loves Me, you’ll see yet another new character. Without losing its playful, enticing qualities, this staircase has lost the mystery of Nine and the gravitas of Assassins. For most of the show, it is a very real, very functional element of a fanciful perfume shop painted vibrantly with dimpled texture and wrought iron flourishes, it has a clear landing outside the owner, Mr. Maraczek’s, office. But near the close of act one as Mr. Maraczek learns of his wife’s infidelity, he seems to spiral into the depths of depression even as he climbs, alone, to the top.

Once you’ve allowed yourself to see it, you will find there are opportunities to ask meaning- making questions about the things on stage in nearly every show. Design elements begin to echo off one another in ways that perhaps not even the designers intended but are true and personal for each audience member. As I watched the final moments of Roundabout’s True West, which I can safely talk about now without spoiling, the back wall of mom’s home disappears, and we are magically in a sunset desert, where the men of this family inevitably end up, doomed to rail against each other and the futility of fate until the day they die. Then the Donald Judd-like concrete frame that has contained the whole story and been used for transitions lights one last time- its fixtures facing out to the audience in a shade of blue so pale it seems white hot. The idea of heat is reinforced by the wiry caging that covers the tube filaments, as if they would burn you if you could touch them. Trapped inside and because of American consumption, these two brothers who could not seem more different, have both bought the idea of maleness from the self-made titans of commerce and lonely cowboys of the west – it’s not a tempest in a teapot, it’s a wasteland inside a toaster. Thinking about objects in this way, that something as small as a toaster or as large as a staircase has as much thought put into it as each word of dialogue or casting decision, opens a whole new world of interpretation and potential for connection.

March Kudisch and Denis O'Hare in the 2004 Roundabout production of Assasins. The 2002 cast of Nine. The set of the 2016 production of She Loves Me. All photos by Joan Marcus.

Want to reach out to James? Contact him at jamesm@roundabouttheatre.org